Why Spotify’s new audiobook streaming could kill off reading forever

Chapters sold as ‘tracks’? Ad breaks between each paragraph? The streaming platform could fundamentally change the way we consume books, writes Professor Matthew Rubery – which means that it could change the way books are written, forever

This week, the book world is gathering at Kensington’s Olympia exhibition centre for the London Book Fair, one of the largest events in international publishing. But this London Book Fair looks different than years past.

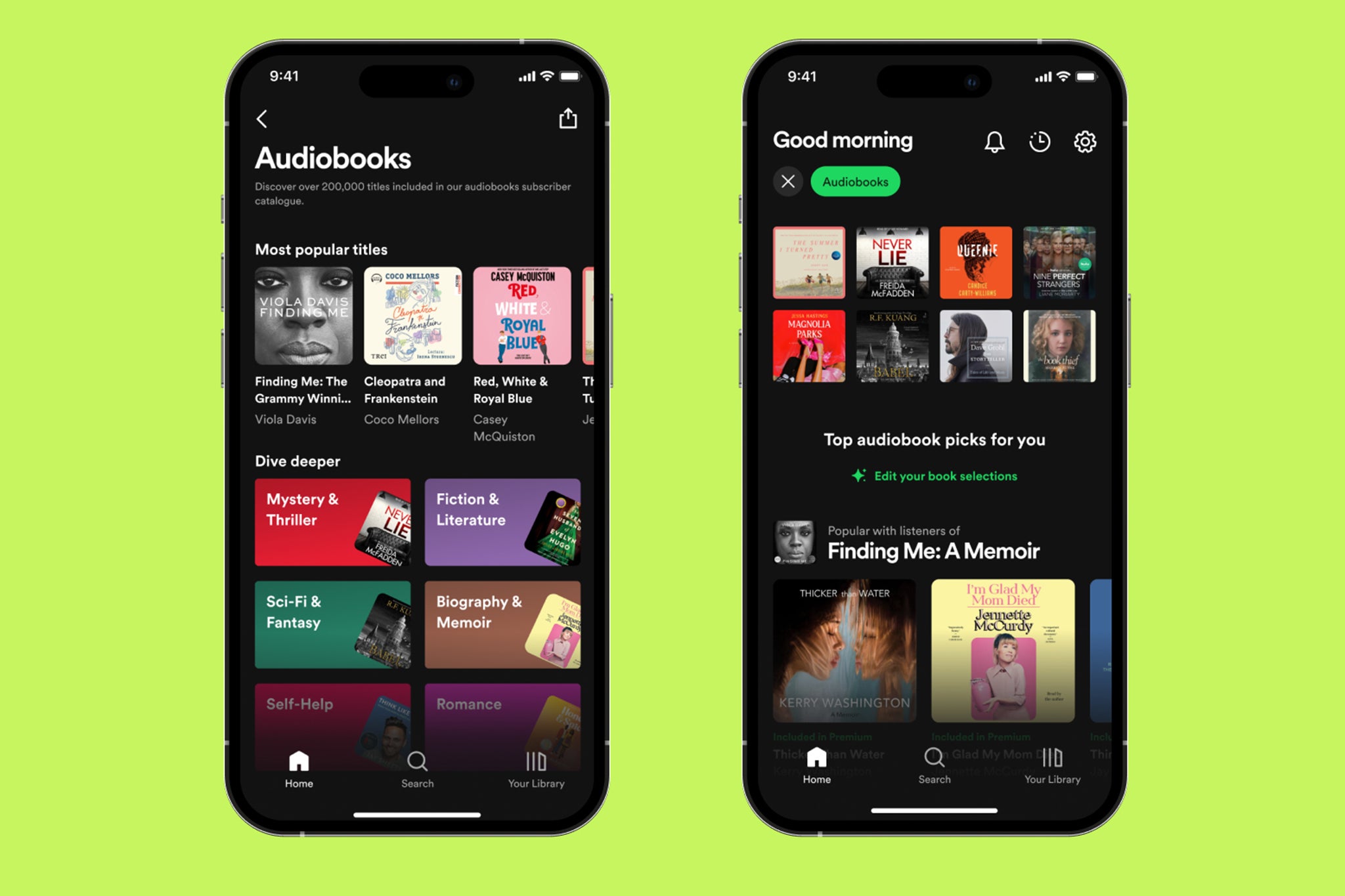

Why? Well, Spotify – the newest entrant into the literature market with its audiobook streaming offering – is everywhere you look, with a big sponsorship presence and participation on multiple panels on the future of audio.

And hear this: readers, authors and publishers should be very wary of any future with Spotify at the centre.

That’s because right now, audiobook readers have never had it so good. The format’s meteoric rise in popularity over the last decade is partly due to how easy it is to listen to them. And with Spotify’s decision to begin streaming audiobooks, it just got even easier – but with a catch: for although Spotify is positioned to give listeners even more convenience, access and options, streaming will be bad for audiobook fans in the long run.

I’m no technophobe when it comes to books. As someone who has listened to audiobooks for most of my life, I’ve watched the evolution of audiobooks – from vinyl records to cassette tapes to compact discs to MP3 files shared over the internet – and there have been benefits to each new iteration.

However, I worry about the potential consequences of following a path that has already devastated other creative industries. Beyond the disastrous effect streaming has had on compensation for creators, Spotify’s entrance into the world of streaming music has led to clear and concerning transformations to the art form itself.

These changes will be immediately apparent to anyone who grew up listening to albums. Songs now start with a chorus; those songs are shorter, with more songs per album. The discovery of new and different sounds is limited. Music consumption is now more passive, distracted and functional, often ruled by the biggest names and labels. The creation of music as artistic expression is changing to appease the Spotify algorithm – and I fear books will be next.

It is easy to imagine a similar literary future: Books written with a climax within the first 30 pages to decrease “skip rates” and game the algorithm; plots optimised to shoot up the “discovery chart” and capture attention; publishers paying for authors to be featured on “New Book Friday”; or your favourite novelist releasing their new book as dozens of staccato “tracks”. Get ready for the deep absorption in imagined worlds rightly cherished by readers to be interrupted by commercials asking if you want fries with that novel.

Streaming will push audiobooks further away from print media like books toward audiovisual entertainment, including music, film, television, radio, and podcasts – more “audio” less “book”.

Spotify is not the first to experiment with streaming audiobooks, and the initial data is not encouraging for anyone who cares about literature. In Sweden, where Storytel dominates, the “best streamers” are practically synonymous with crime fiction – a genre that centres on gripping plots and dialogue.

The research that has been done on this topic by Uppsala University’s Karl Berglund and Mats Dahllöf confirms that the most popular audiobooks tend to be shorter, more straightforward, and stylistically simpler than their print counterparts. Although nothing is stopping people from listening to Moby Dick, the way people consume books seems to influence the types of books they choose. Streaming favours the streamlined.

How will cash-strapped authors respond to the pressures and rewards of this new form of audience capture? Will metrics changing how literature is written mean that listeners will lose out on the elaborate benefits to our brains provided by “deep reading”? Will authors be incentivised to write ambient literary soundtracks rather than the next The Catcher in the Rye? Will the discovery of new voices be at the whim of an algorithm designed to manipulate our mood or maximise listening time?

Streaming might be the future of audiobooks. Nordic countries even prefer streaming audiobooks over other ways of reading. In 2020, more than half of all books sold in Sweden came through digital streaming services. Stockholm’s Storytel has responded to book-streaming’s success with “audio-first” storytelling that bypasses print altogether. It remains to be seen how the audiobook’s ascendancy will influence authors accustomed to writing manuscripts for the eye instead of the ear.

Spotify insists that a larger audiobook audience will mean more revenue for authors and publishers, but things get complicated here: first, a larger audience is no guarantee. As former Apple and Google executive Kim Scott has warned, the new music market is shrinking in the streaming era.

Second, streaming will only benefit readers if the people responsible for making audiobooks – writers, editors, sound engineers and voice actors – are not cut out of the decision-making process or the profits. Those who make a living from writing are especially alarmed by musicians’ horror stories about vanishing royalties. Writers may face even more dire prospects since books are usually not replayed, and the lost revenue can’t be recouped through touring or merchandise sales.

The Authors Guild in the US and the Society of Authors in the UK have voiced several of these concerns, including objections that Spotify’s licensing agreements were negotiated with publishers with no transparency with agents or authors. Some writers did not even know their books were available on Spotify.

Authors must reserve the right to opt out of subscription services if their concerns are not addressed. There are precedents with existing players: Cory Doctorow and Brandon Sanderson made headlines after pulling their books from Audible to protest the platform’s payment terms and other policies – though at considerable cost, which not all authors would survive.

Here’s where consumers have a role to play – by voting with your ears. Sustainable listening means choosing platforms that support publishers, artists and the delicate ecosystem required to produce high-quality audiobooks that do justice to the format.

Libro.fm supports local bookshops with every purchase, for example, and OverDrive’s Libby sources audiobooks from your local library. Curated apps promoting the work of small and independent presses have started emerging, too. Some publishers even offer books directly, like Princeton University Press’s app, which should help turn more academic titles into audiobooks.

Let’s avoid making the same mistakes made in the rush to stream other forms of entertainment because while I have real concerns, I remain optimistic about the evolution of the audiobook industry – as long as the people responsible for making them don’t go extinct in the process.

Matthew Rubery is a professor of modern literature at Queen Mary University of London, author of ‘The Untold Story of the Talking Book’, and a member of the Coalition of Concerned Creators

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments