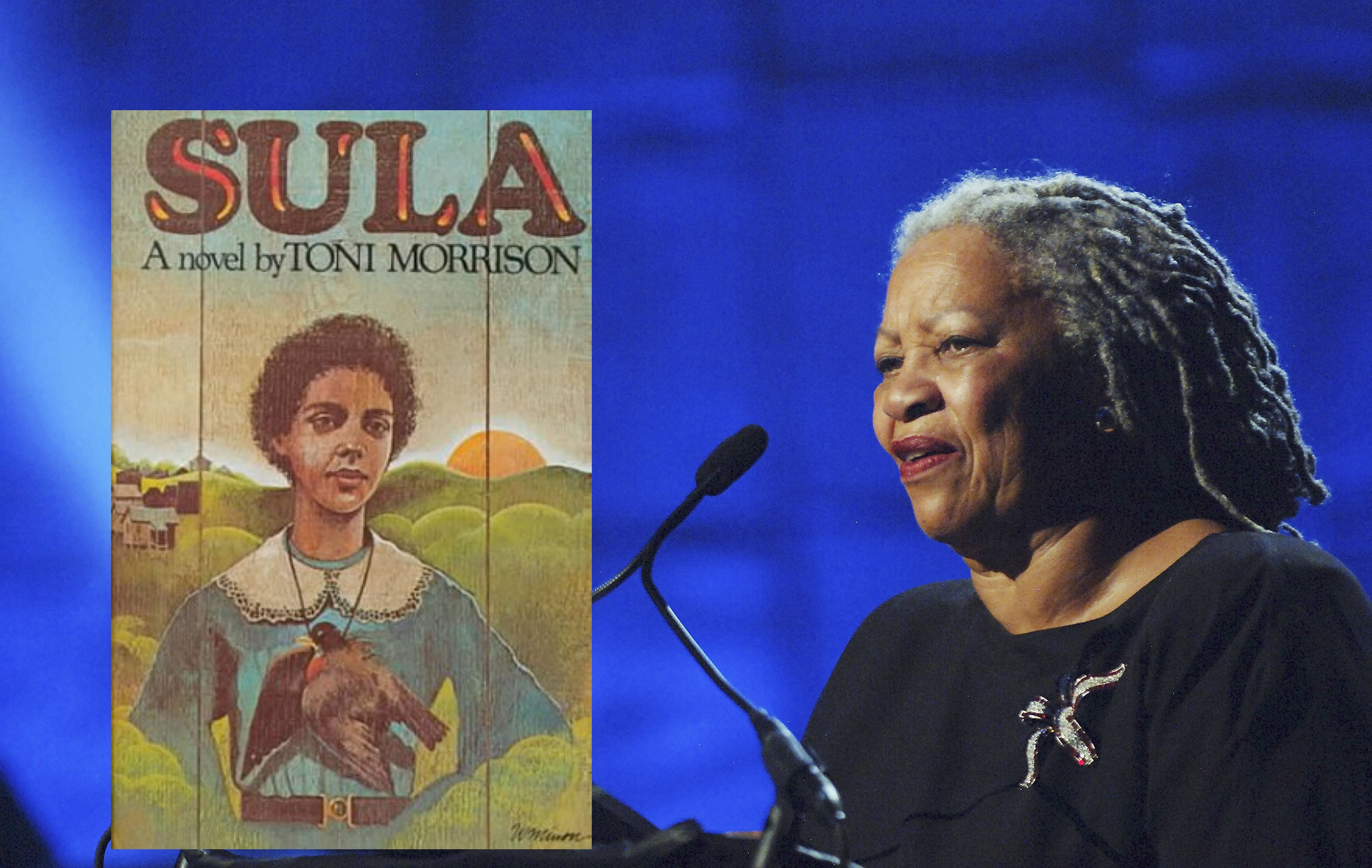

Book of a lifetime: Sula by Toni Morrison

From The Independent archive: Jackie Kay has a piece of her heart stolen by the eponymous character – part myth, part woman, part mirror, part warrior – and learns what it means to ‘go on a real trip’

The first Toni Morrison book I read was The Bluest Eye. Like all loved books, I remember exactly where I was when I read it. I was living in a squat in Vauxhall and Brixton was burning in the 1981 riots. The Bluest Eye told the sad story of Pecola Breedlove, a young Black girl who dreamed of being white; but it was Morrison’s narrative voice that pulled me in, held me tight and made a friend of me for life. I had never come across anything like it – a strange and heady mix of lyricism, and hard realism. It was poetry; it was story. I was hooked. I rushed back up to Sisterwrite bookshop in Upper Street and returned with Sula and Song of Solomon, gobbling them down, impatient for more.

I loved Song of Soloman, particularly the strange and wonderful character Milkman Dead, but Sula stole a piece of my heart. Morrison has said that she wrote the fiction she wanted to read. Discovering her work then was astonishing. I was 20 and just forming. There was something miraculous in finding these Black characters in fiction who were so real, who were made for themselves. I had never come across anybody like them. They had a profound effect on me. They held up an odd mirror.

Nel Wright and Sula Peace are both only children, daughters of distant mothers and incomprehensible fathers. In 1922 they are both 12, “wishbone thin and easy-assed”. Sula and Nel have the immediate intimacy of friends who seem to have known each other all their lives, “because each had discovered years before they were neither white nor male and that all freedom and triumph was forbidden them, they set about something else to be.”

In a short novel of only 170 odd pages, spanning 50 odd years, Morrison captures both the excitement and vivacity of their girl friendship, and the terrible loss and sadness of its destruction. The women are split into opposites. Nel, the conformer; Sula, the outsider – “Like any artist with no art form, she became dangerous.” But as Eva, Sula’s grandmother, eventually points out to Nel, there was no real difference between them. Morrison makes you question small-town morality. Hatred of Sula allows The Bottom (the town in the uplands of Ohio, a character in its own right) to thrive. Peopled with a fantastic cast, Sula creates a magic spell. Her return to Medallion circa 1937 is accompanied by a plague of robins.

Sula is part myth, part woman, part mirror, part warrior. Morrison does not judge her. Sula is the quintessential outsider, completely strange and utterly compelling. When Nel finally realises at the end of the book that it was not her husband she had missed, but Sula all along, I find myself crying. Each time.

When Nel as a girl goes on her first and last trip out of Medallion to her great-grandmother’s funeral, Morrison writes: “But she had gone on a real trip, and now she was different.” That’s what it is like reading Toni Morrison. You go on a real trip and now you are different.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments