What will post-Covid Britain look like for the black community?

As we reflect on how the pandemic has affected Britain, Seun Matiluko looks at the impact of Covid on the black community and asks how the past 12 months have changed the conversation about race in this country

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Like the “post” in postcolonial, the term “post-Covid” seems contradictory, given the ongoing impact it has on our lives. Even as cases continue to fall, and with the success of the vaccine roll-out, coronavirus is still with us. We’re still wearing masks when we go to the shops, staring into webcams as we work from home, and cautiously slathering on antibacterial products whenever we go outside.

Although restrictions are slowly easing, many are still considering the ways the pandemic has affected the lives of our varied communities in Britain. Much-discussed have been the Black British communities, made up mostly of people of African and African-Caribbean descent.

As the Commission on Race and Ethnic Disparities report, published this week, noted, people of black African and black Caribbean descent were far more likely to die during the first and second waves of the pandemic than white people.

Covid-19, and how it has impacted the Black British community, has not only been a health issue, though; it has, and continues to be, a political one, too. Across party lines, politicians have been discussing not only the present impact of the pandemic on black British people but what its future impact could look like for these communities as well.

The report was commissioned in response to the protests that erupted after the murder of George Floyd last year. Opinions have become sharply divided over political lines now that the report’s findings have been published. Particularly contentious is the suggestion in the report that the term “institutional racism” is used too frequently “to describe any circumstances in which differences in outcomes between racial and ethnic groups exist in an institution”.

Politics is something that many black British people have been considering over the pandemic. From disproportionate death rates and the murder of George Floyd, to vaccine hesitancy and the lack of public outrage over the disappearance and death of Blessing Olusegun, black British people have been considering their positions within British political discourse.

For Matthew Kayanja, Oxford University student and former co-chair of the university’s Labour Club, these events have made him reflect on his own politics. In particular, the death of Floyd and the growth in protests against anti-black racism globally made him think more about racism and how “racial politics is not [just] some abstract thing”.

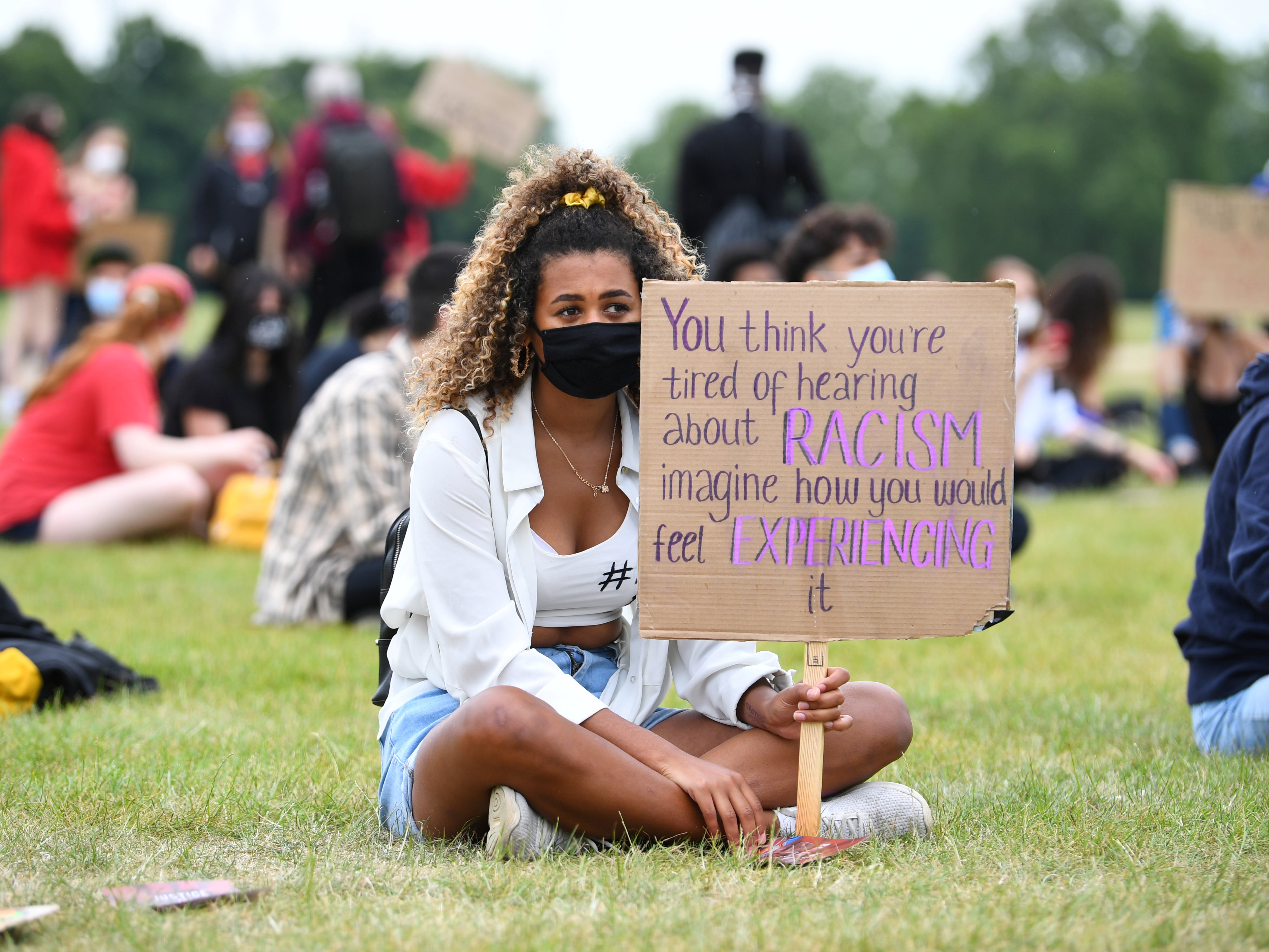

After all, many of his peers joined the thousands of young black people protesting across Britain last summer, marching under signs reading “Black Lives Matter” and “The UK Is Not Innocent”. Protestors came out against police brutality in the US, but also against immigration, health and criminal justice inequality in the UK.

Jermain Jackman, a socialist and anti-racism campaigner, thinks that what we saw last summer was only the beginning of what he has called a “black British renaissance”. As Jackman argued in an article for The Fabian Society: “Just as the Harlem Renaissance created a new spirit of social consciousness and commitment to political activism, it is time now for the emergence of a black British renaissance that builds on the momentum the BLM movement has generated.”

And for Ismael Lea-South, a political independent and the director of The Salam Project, working from Brent to Moss Side to root out gang crime and extremism in black communities, it’s about time for a black British reawakening.

Lea-South has grown frustrated by the lack of political literacy he sees among young, black British people. He tells me that he was dismayed to see some protesters talking more about symbolic issues, like statutes, rather than structural ones: “If you bring down a statue, racism is still there.” A poll recently conducted by the Henry Jackson Society, a neo-liberal think tank, found that only 16 per cent of black British people support tearing down statutes.

Lea-South has also been surprised by the lack of political flexibility he sees among young black British people. He believes that the Labour Party has been taking the “black vote” for granted and that it is high time black communities become “more politically belligerent”.

It is true that, according to the Runnymede Trust, black British people are more likely to vote Labour than any other political party. However, it is notable that, while African-Caribbean support for Labour has been increasing since 2015, black African support for Labour has slightly decreased. It is hard to come to any firm conclusion as to why that is, perhaps because, as Lea-South reminds me, trying to group diverse black populations under homogenising labels like “Caribbean” and “African” often blinds us to the true diversity of black Britain.

“Black people in the UK are not a monolith community,” he says. “Just among the Nigerian community in the UK you’ve got the Igbo, you’ve got the Yoruba, you’ve got the Hausa. Then you have Caribbean gatherings, and you see predominantly Jamaicans and then you go to another place and you see predominantly St Lucians. The black community is heterogeneous.”

Nevertheless, some have argued that divergent black support for Labour in the past few years could be explained by the fact that black British people, and particularly black West Africans, are more socially conservative than they are presented in sections of the mainstream media. However, it is doubtful how much that explanation rings true for younger black British people, as the young tend to be more politically progressive than their elders.

Policy researcher Kim McIntosh tells me: “We’re guessing when we ask, ‘what do young, black people think?’.” While many pundits have discussed black British voting patterns, few have considered how older and younger black British generations diverge. Kayanja’s guess is that most young black British people are “very liberal” on the whole, but on economic issues, he is “not so sure”. McIntosh agrees, pointing to a section of young black British Twitter, known colloquially as “Roc Nation Twitter”, which is made up of what she thinks are “prime Tory voters” due to their tweets, which align more with a capitalist than a socialist world view.

Whatever the case, it does seem that some young black British people have grown tired of the Labour Party during this pandemic. Many recently expressed outrage over the delay in the publication of the Forde inquiry, which includes details of Labour staffers allegedly calling prominent black Labour MPs derogatory names, and many were frustrated by the deselection of black Liverpool mayoral candidate Anna Rothery.

Read more:

For some young black British people, there is a sense that the Labour party does not adequately support its black politicians and for Dawn Butler– the Labour MP for Brent and a former shadow secretary of state for women and equalities – it does appear puzzling that some within the party seem to react more favourably to American black politicians than British ones.

“Kamala Harris’ historic win made me think about our black women firsts in the UK, and how much that doesn’t get spoken about,” says Butler. “Diane [Abbott] was the first black woman to be elected in parliament. I was the first black woman to speak at the despatch box as a government minister. It makes me wonder why there’s such a reluctance to celebrate those things.”

And when our politicians are perceived to be taking black people for granted, to paraphrase Lea-South, it is unsurprising that some no longer feel invested in supporting Labour. Nevertheless, Kayanja, of the Oxford Labour Club, feels that black British people should continue to have faith in Labour because “the Labour Party, obviously not perfectly, defends the interests of black people better” than our current government.

For instance, many within the Labour Party have adopted arguments in support of increasing black British representation in the national curriculum, something which polling indicates most black British people would support. Labour leader Keir Starmer has previously said: “Black British history should be taught all year round, as part of a truly diverse school curriculum that includes and inspires all young people and aids a full understanding of the struggle for equality.”

In contrast, the Conservative front bench have offered conflicting statements about whether our national curriculum needs reform, although it should be noted that, while the race report stated that calls by black activists to decolonise the curriculum were “negative”, it has recommended that the government should work “to tell the multiple, nuanced stories of the contributions made by different groups that have made this country the one it is today”.

In line with political debate on black British representation in the national curriculum, Labour MP Abenna Oppong Asare spearheaded a Black British History debate in the House of Commons last year. However, a significant proportion of media discussion of the six-hour debate did not focus on the content of the debate but rather on its final moments, where the minister for equalities, Kemi Badenoch, criticised Black Lives Matter, critical race theory, and the concept of “white privilege”.

Her speech was received favourably by many on the political right but some black British people disagreed with what she had to say. As Jackman told me, the video of Badenoch’s speech “ended up in my WhatsApp and people were saying, ‘how can she say these things?’”

However, Lea-South supported some of what Badenoch had to say, particularly because of the divisiveness he sees within anti-racism discourse from those on the political left. As he explains, “there are some who, when they’re talking about white privilege can come across a bit aggressive, a bit disrespectful, a bit divisive”.

As the report noted, the term white privilege can be “alienating”, “counterproductive and divisive” and Lea-South thinks that when discussing the extent of racism in this country, it is important to stress that “as a black person, in the West, Britain is the best place to be” but also to acknowledge that there is “room for improvement”.

And it seems that the commissioners of the race report would agree with him, claiming that Britain has the capacity to be a “beacon to Europe and the rest of the world”. For instance, the commission noted that while racism persists in Britain, only 21 per cent of black British people have experienced racial harassment in the last five years, a much lower number than 51 per cent in Ireland or 63 per cent in Finland.

However, black British people are British, not Finnish and 75 per cent of black British people, according to data commissioned by the Joint Commission on Human Rights, believe that their human rights are not as equally protected as white people’s.

Some, including Lord Simon Wooley OBE and Baroness Doreen Lawrence, believe the race report did not do enough to assess the extent of anti-black racism in Britain. For instance, when positing why black people have a higher death rate from Covid-19, the report dismissed claims of racism, stating that “many analyses have shown that the increased risk of dying from Covid-19 is mainly due to an increased risk of exposure to infection”. Yet others argue that the reason why black communities face an increased exposure to infection is due to racism.

Nevertheless, although Samuel Kasumu, the government’s senior ethnic minorities advisor, resigned shortly after the report came out, some might argue that a report conducted by mostly non-white people likely would not intend to dismiss concerns about racism.

However, Kayanja is sceptical of government advisors, and particularly politicians on the political right, being shielded from criticism because of their race: “It is very interesting that there’s a sort of industry of black person saying why the ‘woke’ are bad and the Conservatives really eating it up.”

But Siobhan Aarons, co-chair of Conservative friends of the Caribbean and co-founder of Conservatives Against Racism For Equality, believes that many of the political right have worked to try and further racial equality in this country and that the Conservative Party, in particular, better represents black British people than Labour. She argues that younger people would more readily recognise this if they exercised more “critical thought” and less “reaction” based politics.

Read more:

For instance, she thinks that the Conservative Party should get more credit for the moves they have taken to diversify: “This cabinet is ethnically diverse, even if you compare those two front benches.” In stark contrast, the Labour Party has had difficulty in increasing black male representation. As Jackman explains: “The Labour party speaks a lot of good game about equality and fairness but in practice, they fall short quite drastically.”

However, he thinks that while the Conservative Party may be doing better in this regard, “it’s only superficial. We see that it’s only black and brown faces in high places, rather than actually pushing for an agenda of racial equality.”

Whatever one thinks of these assessments, Aarons suggests that politicians on both the left and the right often utilise identity politics when talking about hot button racial issues, as “a comms person for a political party [would likely not] put forward your male-pale-stale” politician to make comments on issues like “the police’s treatment of black young men... for the fear of how it will be perceived”.

For her, this is the unfortunate reality of contemporary British society where “there is a fear by those who genuinely care about anti-racism… [They] are concerned and worried about saying the wrong thing.”

And words do matter, as the commission noted when they advised the government to no longer use the term “Bame” because it masks “huge differences in outcomes between ethnic groups”.

As Aarons explains: “‘Bame’ has been important and useful for policy [but] we are very much in a time where [people of colour are] reclaiming our own identities.” While she doesn’t want to “limit looking for representation purely in terms of skin colour”, she still wants to “know that, irrespective of any of that, I can get there if I want to”. She looks forward to the day when someone of Caribbean descent, in particular, is on “the front bench in government”.

She also hopes black people on the political right, or perceived to be on the political right, will soon receive far less vitriol on social media than they currently do. She, like many other black British conservatives and, most recently, the black commissioners of the race report, have regularly been called “coons” and “Uncle Toms” by other black people online.

Kayanja thinks that this may come about because some black people perceive black people on the political right to be promoting messages that are harmful to the community. However, Kayanja believes it is wrong to call those one is ideologically opposed to names: “It is inherently demeaning to tell somebody that, ‘you’re not of a certain race’, just because you don’t have a certain political belief”.

And in particular, McIntosh argues, it is counterintuitive for black people on the political left to call certain back political commentators on the political right names because it will just end up giving “credibility to their argument that racism isn’t real and that the people most racist to them are black people”.

McIntosh’s arguments reflect Aarons’ disappointment with the few black British conservative voices that our mainstream press regularly spotlights: “The face of non-left thought is an extreme one if you’re black.” She elaborates: “We love a more extreme position right now [...] when you think of the few black voices on the right or who aren’t lefties, they have a particular position which reacts strongly with many black people. And I am not one of those, I am one of the silent majority who sits in the middle, who don’t get heard because we’re just maybe not that interesting.”

In line with this moderation, Aaron’s Conservatives Against Racism For Equality said that while some statements in the race report “require clarification” they “commend the report’s recommendations”.

It is clear, then, that the race report has further highlighted the need for informed debate as our country emerges from the pandemic. However, it is important to recognise that the end of the pandemic will not mean an end to inequality and tackling some of these long-standing inequalities will require action from people from all walks of life because, as Dawn Butler reminds me: “Everybody will have a role to play.”

One thing is for certain, we can never go back to normal after this pandemic. As Jackman tells me definitively: “I want a better normal because the old normal didn’t work for black people.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments