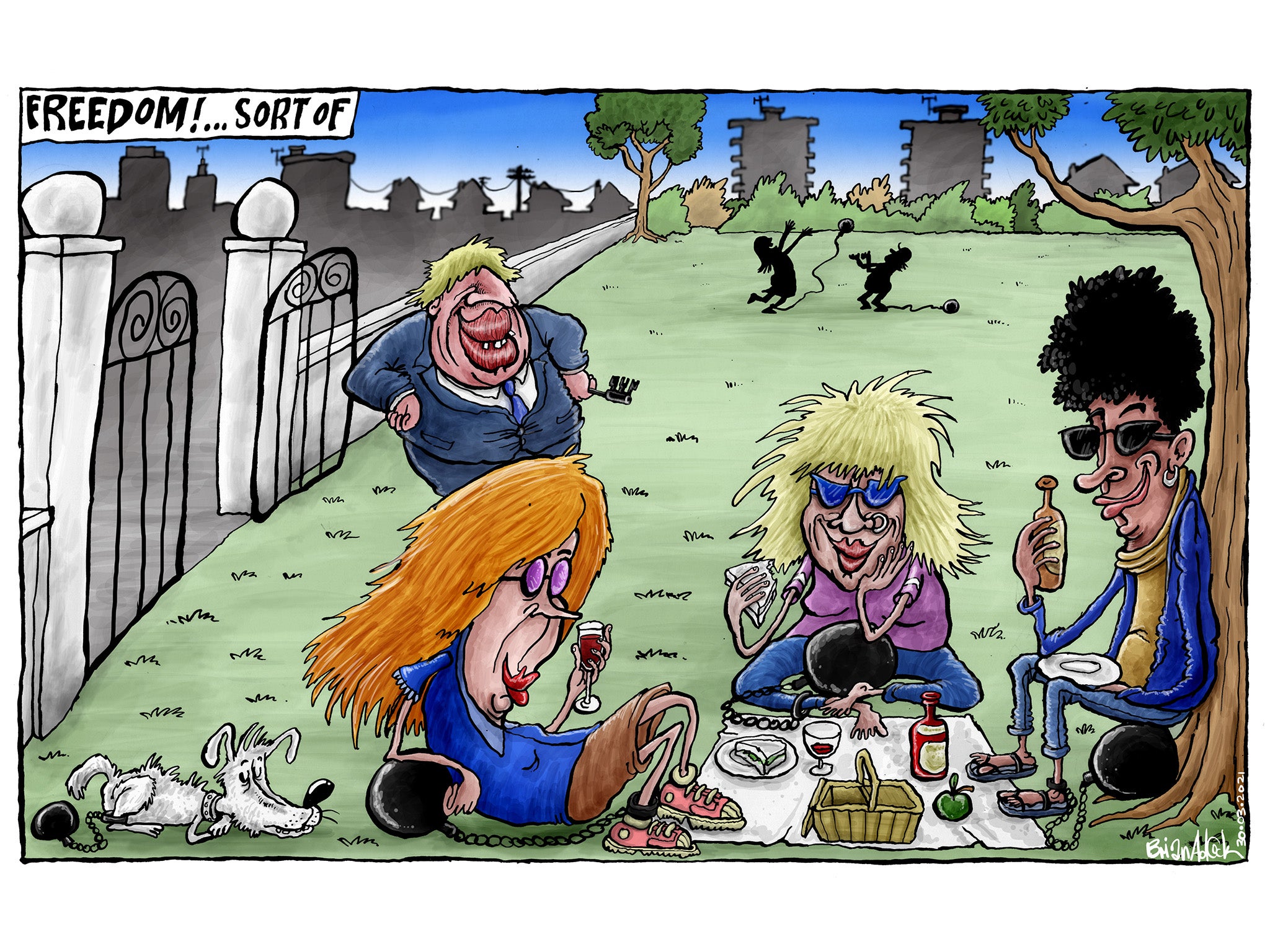

The gradual easing of lockdown continues across the four nations of the United Kingdom. Generally, it is as welcome as it is delayed – a year ago, Boris Johnson suggested lockdown would last for three weeks.

Since then, there have been many other false dawns, as well as postponed weddings and holidays. The return to normal, whatever “normal” now means, will take weeks longer. Scotland, Wales, Northern Ireland and England went into the first lockdown together and will emerge from it, more or less, together.

This is largely down to the highly successful rollout of the vaccine, but that rollout is far from complete, and the danger of complacency, particularly among younger citizens, is real.

As expected, the infection rate has edged up among older children since the schools were reopened in England. In many areas, and among some ethnic groups, as we report today, a dangerous combination is developing: a still-high case rate and a relatively low vaccination rate. In some cases, this will be exacerbated by an overly relaxed attitude to social distancing and hygiene precautions, as well as greater willingness to meet indoors in larger groups than permitted. The weather is not yet bright enough to have removed that temptation.

Meanwhile, the third Covid wave is hitting western Europe, and the “variants of concern” are multiplying. This is bad news for all, because if there is one lesson that has been learnt in the past 12 months, it is that the coronavirus recognises no borders and doesn’t discriminate among its victims, aside from its tendency to most affect the elderly and clinically vulnerable.

The wide regional discrepancies that may emerge as lockdowns are eased will cause some to argue for a renewal of the “tiers” system trialled last autumn. At best, the tiered approach was only partially effective, and even then not for so very long. In due course, the second lockdown soon overtook everyone. The modest differences in priorities set by the devolved authorities are about as far as such a geographically based policy should go.

Read more:

Which leaves the slowdown in the administration of vaccines. There are mixed messages about this, and its causation, but the conclusion is that the rollout is going more slowly than planned. Rather than speeding up the unlock, as many advocated when the programme was at its unexpectedly efficient peak, is there now a case for slowing down the relaxations, as the jab rate flattens off? The answer, as ever, lies in the data, and the expert interpretation of that.

The Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies has ensured that the next relaxation is entirely contingent on progress on cases and mortalities, even though the effect of the disease, for now, will probably be lessened for those unfortunate enough to contract it.

The unlock, in other words, should continue to be governed by hard data rather than boosterish hopes, and the dates given by all four UK administrations remain as they were originally – the earliest possible times for new relaxations rather than firm deadlines. It is a message that could do with some reinforcement.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments