Political advisers are now too scared to tell ministers the truth

Civil servants have a vital role to play if Sunak is to keep his promise of ‘integrity, professionalism and accountability at every level’, writes Andrew Grice

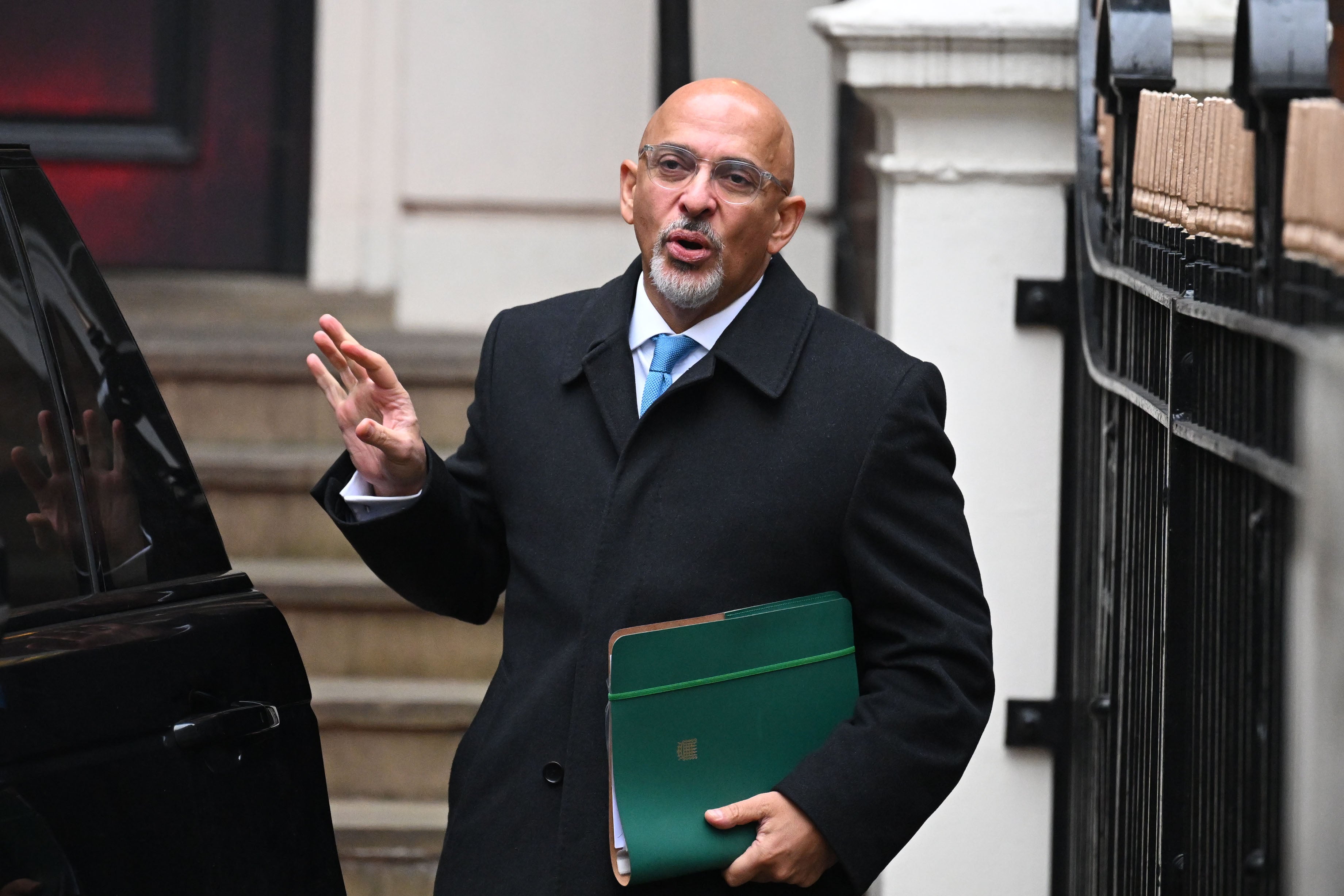

The Two Chairmen pub in Westminster is a favourite watering hole for civil servants. This week it was a fitting place for an after-work gossip about the controversies engulfing the “two chairmen” – the Conservative Party’s Nadhim Zahawi and the BBC’s Richard Sharp.

However, the saga has raised uncomfortable questions for the civil service, as well as for politicians and the BBC. Did Whitehall officials do enough to warn Boris Johnson, Liz Truss and Rishi Sunak about the HMRC inquiry into Zahawi’s finances? Why did Simon Case, a great survivor whose days as cabinet secretary finally seem to be numbered, help Johnson secure an £800,000 loan facility while prime minister? And why did Case apparently not ensure that Sharp’s role as a go-between in this arrangement was declared when he applied successfully for the position of BBC chair?

Characteristically, some politicians are preparing to blame civil servants for not making sure the rules were upheld in both affairs. But Whitehall officials argue they are in an impossible position. Some think the Zahawi and BBC controversies highlight a very real problem: civil servants are now reluctant to warn ministers they may be breaking the rules because they fear their objections will be dismissed (as they sometimes were by Johnson), and because speaking truth to power could harm their careers.

As one long-standing official told me: “The atmosphere is one of mutual distrust. It encourages people to keep their head down and let ministers stew in their own juices, rather than warn them they might be about to make a mistake. Then there’s the inevitable blame game when things go wrong.”

It’s the politicians – not their officials – who have driven a coach and horses through the rules and conventions since the 2016 Brexit vote. Under Johnson, the norm became a casual relationship with the truth (Partygate is just for starters); a readiness to break the law (ripping up his own Brexit agreement or proroguing parliament); trying to change the rules when his mates broke them (Owen Paterson); and ignoring findings against them by his ethics adviser (Priti Patel kept her job even though she broke the ministerial code).

This was coupled with attacks on a civil service “blob” accused of blocking Tory policies, and on “woke” Remainer officials accused of laziness for wanting to work from home.

The relationship between ministers and politically neutral civil servants came close to breaking point during Johnson’s premiership. An inquiry found that Patel had bullied officials, and multiple bullying allegations against Dominic Raab (which he denies) are still being investigated. Truss’s needless sacking of Tom Scholar, the Treasury’s respected permanent secretary, has left deep scars in Whitehall.

Morale slumped during a year of political upheaval in 2022. Pay is down in real terms, and staff turnover is at a record high. Ministers claim with some justification that the churn leads to a lack of expertise and poor advice, so they rely more heavily on their party-political special advisers.

The ever-growing influence of these “spads” started under Tony Blair, whose government wrongly doubted the neutrality of the civil service after 18 years of Tory rule (Keir Starmer should avoid the same mistake if he wins power).

Some of today’s ministers argue there is little cause for concern because “Boris was a one-off.” They insist the “good chaps” theory of government – in which all MPs are “honourable members” – has reasserted itself under Sunak. But this is dangerously complacent: how do we know there will not be another PM like Johnson? There might even be one called Boris Johnson, given he is dreaming of a comeback this year.

True, Sunak has tried to repair relations with Whitehall, scrapping plans for an arbitrary cut of 91,000 jobs and reversing Truss’s unnecessary clearout at Downing Street. But his uncompromising stance on public-sector pay is hardly helping to heal the wounds.

The civil service is not without blame. It is not as opposed to reform as ministers suggest, but it is also not as open to change as it should be (including people coming in from the private sector). The Partygate scandal reflected badly on civil servants, as well as on ministers and their political advisers.

One useful remedy would be legislation that gave the civil service a statutory duty to uphold the public interest as well as serve the government of the day. In return, officials would be more accountable to parliament, and couldn’t hide behind ministers when things went wrong. The idea is supported by the Institute for Government think tank, and by Gordon Brown’s democracy commission for Labour.

As an example, officials could have a duty to remind ministers about their own code of conduct, and alert the PM’s adviser on ministerial interests if they thought it might have been broken. Such a power would probably be used only very occasionally; its very existence would force ministers to pay more attention to the rules.

Although Sunak’s instincts on propriety are better than those of Johnson and Truss, he might well judge that he has more pressing pre-election priorities than a Civil Service Act. Yet civil servants have a vital role to play as a collective guardian if Sunak is to keep his promise of “integrity, professionalism and accountability at every level”.

He should prove he means it by bringing in a reform that would help to ensure ministers meet the standards they have woefully failed to uphold in recent years.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments