A single-minded visionary… and public enemy number one in Britain for delivering the euro

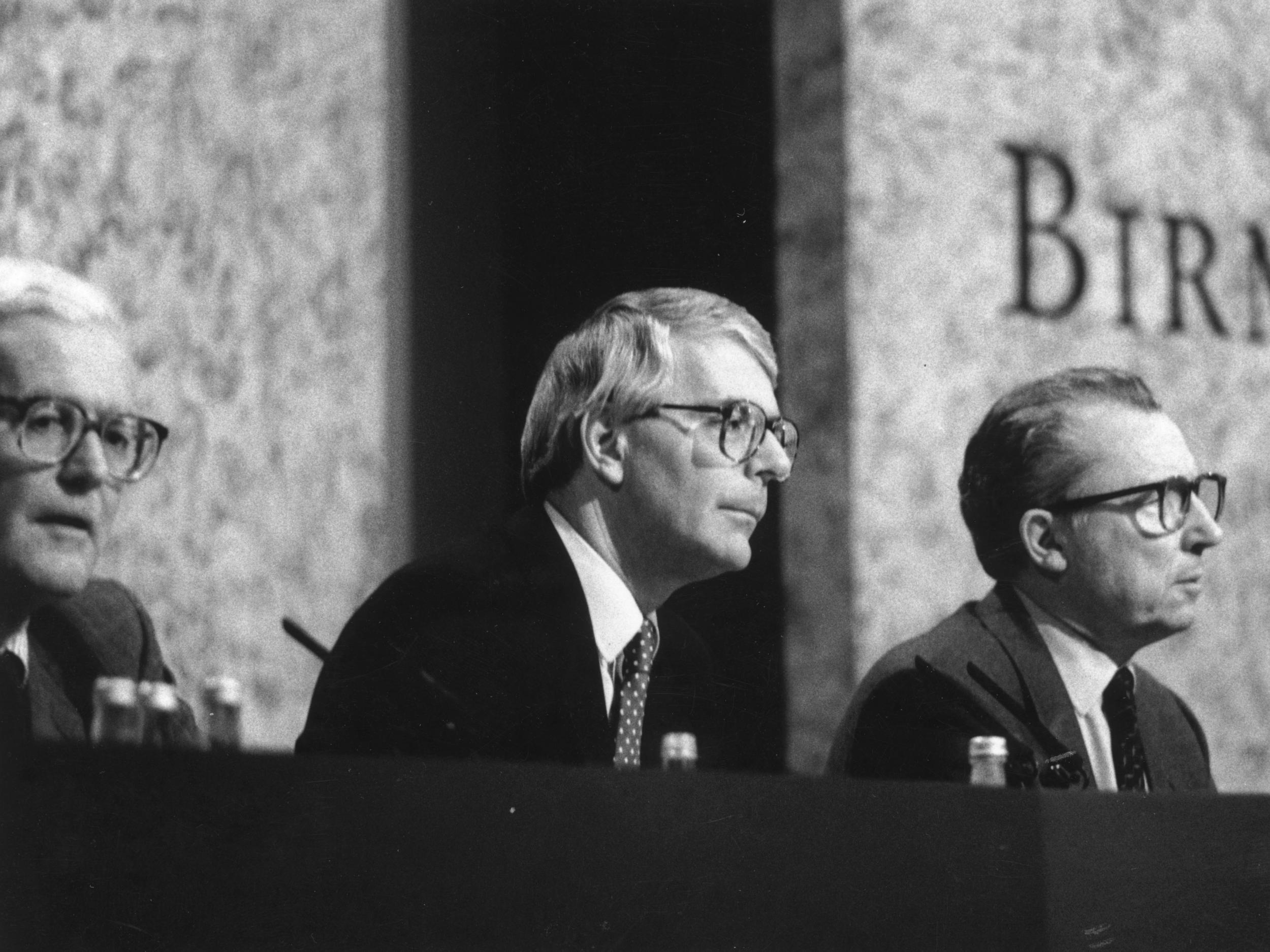

Jacques Delors was short, bespectacled, earnest and bad-tempered – more local mayor (which he once was) than urbane, smooth French charmer, writes Chris Blackhurst. He was also a humanist, honest, and he could not be turned – ever

All you need to know about Jacques Delors is that he turned down the offer to be prime minister of his own country because he decided he would rather be president of the European Commission.

The French president at the time, Francois Mitterrand, was all set to promote his fellow socialist minister of finance, in effect further propelling him towards one day becoming president of France, when Delors said he preferred the Brussels job instead. You can imagine the ridicule his decision would provoke, even now, in some quarters of Britain.

To many, it would confirm what they had long thought: that Delors, who has died at the age of 98, was a joke figure. After all, he was the target of one of the most memorable tabloid headlines, on the front page of The Sun on 1 November 1990: “Up Yours Delors.”

The over-large type was accompanied by two fingers forming the time-honoured rude salute. The sheer disrespect, the graphic, and the article itself – which describes the EC head as a “French fool” – represent classic bile from the paper’s then editor, Kelvin MacKenzie.

“They INSULT us, BURN our lambs, FLOOD our country with dodgy food and PLOT to abolish the dear old pound. Now it’s your turn to kick them in the Gauls. We want you to tell Froggie Common Market chief Jacques Delors what you think of him and his countrymen.”

It’s funny, in that cheeky chappie plucky British way. But it’s also deadly serious. This is what was then Britain’s most widely read newspaper by some distance, inviting “all true-blue Brits to face France and yell ‘Up Yours Delors’”.

Thus was the Brexit campaign born; thus were heroes found, in Nigel Farage and Boris Johnson, who would give Delors and his mob what for. More than three decades later, the feelings induced by that piece, and by the tone it took, still run deep.

Delors’s crime was to promote the idea of a single European currency. Coincidentally, 1 January 2024 sees the 25th anniversary of the euro’s birth – electronically at first, then three years later as notes and coins. Delors’s creation is now the second global reserve currency, only surpassed in strength by the US dollar.

His native France, Germany, Netherlands, Spain, Italy... they all gave up their domestic historical symbols in return for something equally tangible, a monetary system that would unite Europe. That sentence, the same as the mention of Delors passing up the chance of prime minister for EC president, will spark mirth among some. Likewise, that never-to-be-forgotten headline.

To them, he was always Public Enemy No 1, a European technocrat who wished to strip away centuries of identities and traditions and turn the EU into a federalist superstate. It was his ambition and his zeal that prompted Margaret Thatcher to make her landmark Europhobic 1988 Bruges speech.

As Delors himself said: “I think for Mme Thatcher I was a curious personage: a Frenchman, a Catholic, an intellectual, a socialist.” Those last two in particular she found unsettling.

Delors was always on the side of the worker. With him at the helm, Thatcher and her ilk convinced themselves that the EU was intended to become some sort of anti-capitalist, Marxist axis, run by the French and Germans to the detriment of Britain.

It didn’t help matters that Delors was short, bespectacled, earnest and bad-tempered – more local mayor, which he once was, than international, urbane, smooth French charmer. He was also a humanist, honest, and moral. He could not be turned, ever.

He’d achieved many of his objectives, turning the common market into the single market, and devising an umbrella economic framework with a European central bank at its peak before he pushed for the euro.

In the UK, his steps were treated as cause for alarm, even panic. In Europe, while there were misgivings, they were accepted.

The profound difference was not so much his left-wing ideology but his desire that never again should Europe be subjected to war. Like millions of Europeans, he had lived through the years of Nazi occupation and had witnessed the horrors this entailed. It was not the same in Britain. Yes, the country was heavily bombed and the military suffered huge casualties, but the Nazis did not invade – Britain, to that degree, was spared.

Delors made it his post-war mission to build a new Europe, founded on friendship and togetherness. Unfortunately, that often boiled down to a Franco-German partnership and one that involved the development of a superstate – a goal he did not shirk from. As he said: “National sovereignty no longer means much. And experience has shown that voluntary cooperation between states never works. In order to face the American and Japanese challenges, we need to be supra-national.”

In fact, for all the abuse he received, Delors admired the British, convinced that eventually the country would embrace Europe. It was not to be. To borrow an infamous MacKenzie jewel: arguably, where Delors was concerned, “It Was The Sun Wot Did It”.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments