Sleaze is tricky to define but you recognise it when it hits you. It first entered the political lexicon in the 1990s, and it seems never far away. Right now, there is something of an avalanche of the stuff overwhelming the body politic and burying reputations along with it.

Even though people become inured to scandal, and some cases go back a few years, it is surely shocking that more than 50 MPs reportedly face allegations of sexual misconduct. That includes three cabinet ministers, two shadow ministers, and at least one allegation that would constitute a criminal offence.

The latest allegation is one of bullying against Labour MP Liam Byrne. He has been found to have bullied a former member of staff and will be suspended from the Commons for two days. Mr Byrne had been referred to the Independent Expert Panel (one of a confusing number of overlapping standards bodies) under the Independent Complaints and Grievance Scheme (ICGS), a new-ish procedure introduced after a previous spate of bullying and sexual harassment allegations involving the staff of MPs and employees of parliament itself in around 2017. The ICGS is the body, with external investigators, that is looking into the 56 sexual misconduct allegations, and 14 other cases.

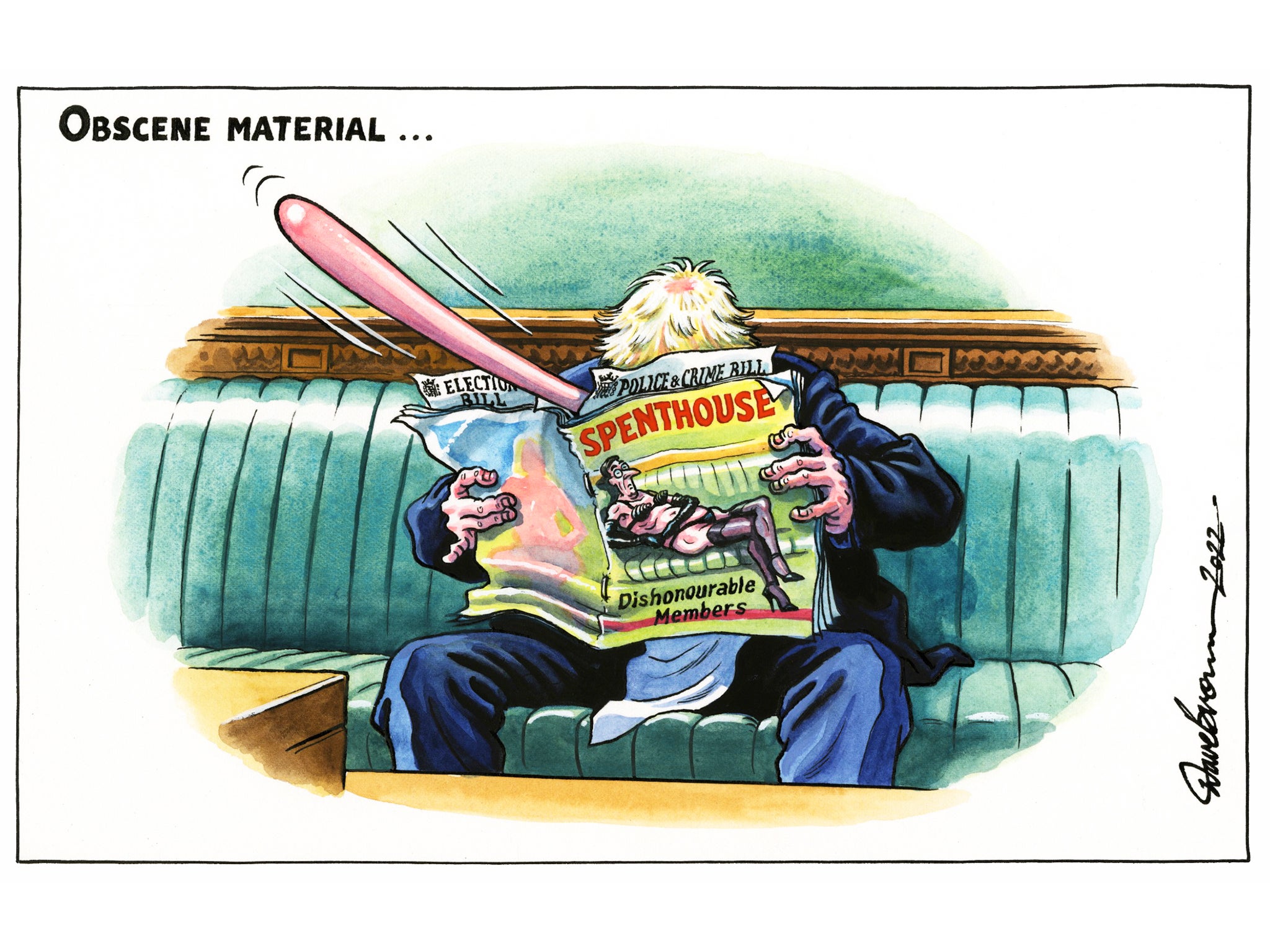

There is also, to the embarrassment of all concerned, an apparently witnessed episode of a member of parliament watching porn on his smartphone in the hallowed chamber itself, and possibly elsewhere in parliament. That too has been referred to the Conservative Party whips, who are in charge of discipline, and the chief whip has in turn referred it to the ICGS.

The porn revelations have raised a series of questions, practical and ethical, and the behaviour certainly seems bizarre. It has to be said that misbehaving MPs, peers and ministers are nothing new. You have to really search to find much precedent for the Thorpe affair, when the then leader of the Liberal Party, Jeremy Thorpe, was tried for conspiracy to murder his former gay lover Norman Scott (he was acquitted, controversially, at the Old Bailey in 1979). But still, the list of recent scandals feels long and suggests a more endemic culture of sleaze.

The MPs’ expenses scandal from 2009 saw a number jailed for fraud, and even the lawful claims for duck houses and the like appalled the public in their extravagance. In recent decades we have had, in shorthand form: cash for questions; cash for honours; cash for access; attempts to pervert the course of justice; “plebgate”; non-doms; lobbying and Greensill; the Dominic Cummings saga; and now flouting of lockdown laws and a subsequent cover-up.

Waves of sexism and misogyny seem never-ending, with Angela Rayner the latest victim. A female MP has also accused a member of Labour’s shadow cabinet of making inappropriate comments by claiming she was a “secret weapon” because men wanted to sleep with her.

It is often said that, despite everything, the UK has a remarkably clean record by international standards, and that the great majority of MPs work hard and honestly. Good works on cross-party causes are rarely reported. But it’s not good enough, given the rock bottom reputation of the political trade. Such cynicism about politicians – that they’re all “in it for themselves”, liars, crooks and philanderers – easily infects trust in parliament and democracy as a whole. It gives populist movements such as Ukip an easy ride. In extreme circumstances, it leads to death threats and terror.

To keep up to speed with all the latest opinions and comment sign up to our free weekly Voices Dispatches newsletter by clicking here

The problem is that no single politician or party “owns” trust and integrity in the system. Those are collective, common goods, but no politician has much incentive to act other than in the most selfish, greedy and partisan fashion. In that sense, it is a wonder that more wrongdoing isn’t uncovered.

There is no shortage of media focus, voter revulsion, penalties – but there seems no cure for the disease afflicting democracy. Every time there is a big scandal indicating a sick political culture, a new watchdog is set up. If parliament and politicians could gain respect by setting up new committees then nothing would ever go wrong.

Too often, though, the procedures have a pantomime quality to them, non-apologies displaying little real remorse, and with light penalties compared with what the average worker might expect for the same misdeeds. Political parties – no different to companies, banks, churches or the media – have a tendency to defensiveness and secrecy when under attack.

Even now the public have no right to know who is being investigated for what, though they are asked to vote for these people, pay their wages, and allow them to employ their wives and children on the public purse (a practice still permitted for long-standing MPs). Creatures of bad habits, our politicos.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments