A wave of irrational anti-Chinese sentiment seems to have swept across the west

Editorial: In Britain, even legitimate concerns about Huawei, Chinese participation in the nuclear power programme and sponsorship of universities have turned paranoid

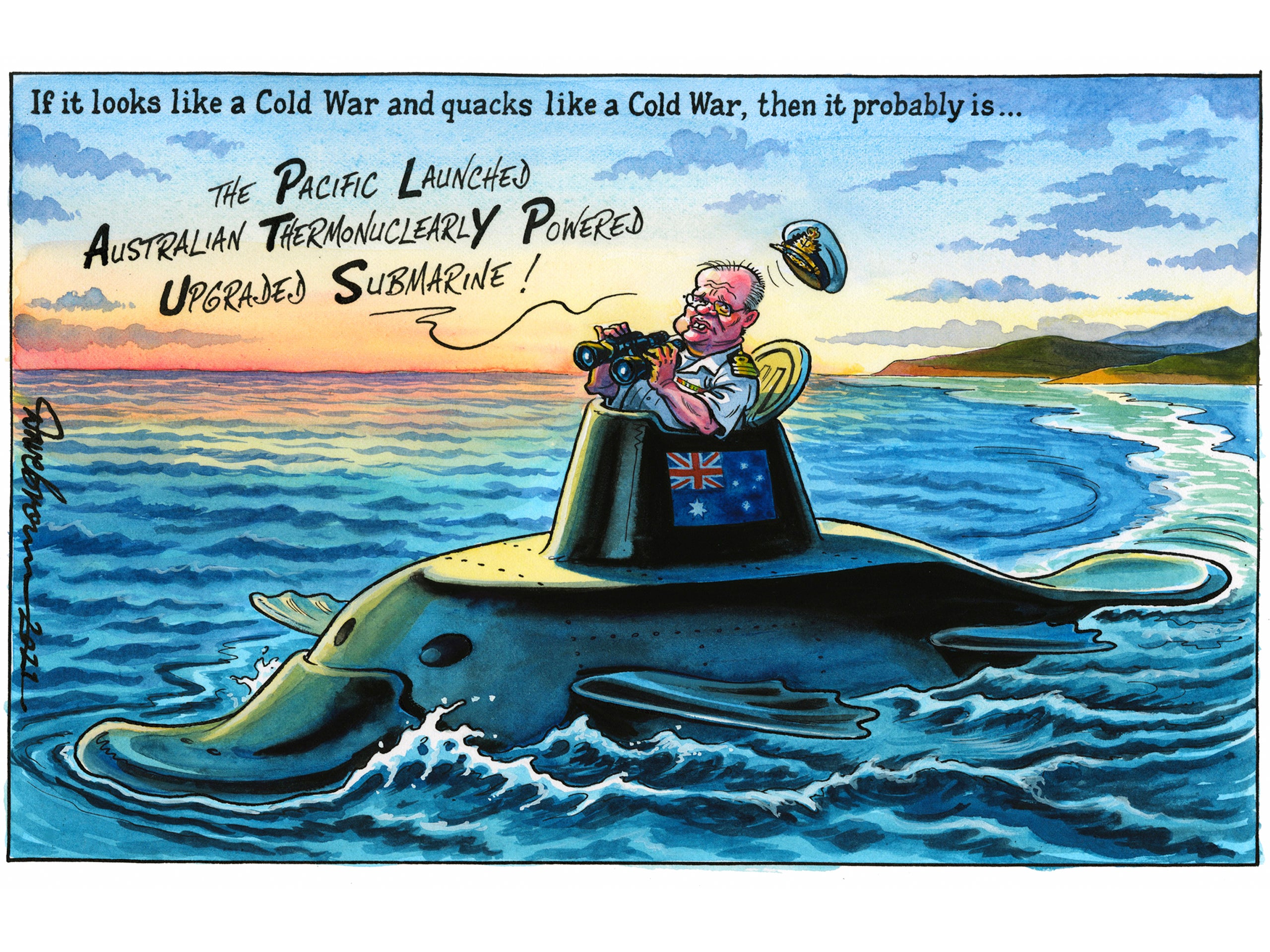

According to the prime minister, the submarine deal and embryonic defence and security pact between Australia, Britain and America – Aukus – is no more threatening to anyone than a koala bear: “Aukus is not intended to be adversarial towards any other power. It merely reflects the close relationship that we have with the United States and with Australia, the shared values that we have and the sheer level of trust between us that enables us to go to this extraordinary extent of sharing nuclear technology in the way that we are proposing to do.”

Pull the other one, as they don’t quite say in Beijing. It looks as if China is being encircled. It is worth dwelling on the view from the east as “global Britain” pivots away from its priorities in Europe and towards the Indo-Pacific region, a slice of the globe the British abandoned – seemingly for good – when they closed the naval base in Singapore, the last relic of empire, a half century ago.

From the point of view of the People’s Republic, Aukus looks very much like another move in a new military alliance aimed at China, and adds, worryingly for them, to the existing diplomatic and defence relationships in the region, led by America – involving Japan, South Korea, Taiwan and (latterly) India.

Sino-Russian relations remain wary, as do China’s neighbours in the South China Sea, such as Vietnam and the Philippines – fearful about expansionism and a “sea grab” for territorial waters. Sometimes it must feel to the Chinese leadership that their only friends in their own back yard are the North Koreans, and that can’t be much comfort.

President Xi’s mouthpieces have, naturally, used state media to condemn the deal, with some preposterous claims about the pact breaking the international nuclear proliferation treaties. As rhetoric heats up, a senior Chinese military expert has said the newly announced pact puts Australia at risk of becoming a “potential target for nuclear strikes”.

The Chinese leadership might be better advised to consider why their neighbours and nations across the world are so concerned about the rise of their country as an economic, technological and industrial superpower, and with an increasingly assertive foreign policy. China is so big almost anything it does will disturb the status quo anywhere on Earth; when even the most gentle of giants steps forward, the land will shake.

China should be well aware of the many concerns expressed around the world about its less gentle steps – the treatment of dissent in Hong Kong, the Uighur Muslim people, violations of international law in the South China Sea, pollution and CO2 emissions, and the Belt and Road Initiative as a form of new-colonialism in large parts of Africa and Asia. Those are the new factors that have turned China’s extremely beneficial re-entry into the world economy into cause for concern, and has led to the early stages of a cold war.

That said, a wave of increasingly irrational and unevidenced Sinophobia seems to have swept across parts of the west, as if China is some sort of clear and immediate threat to national integrity. In Britain, even legitimate concerns about Huawei, Chinese participation in the nuclear power programme and sponsorship of universities have turned paranoid. There is, almost incredibly, talk of war over Taiwan, with no understanding of the sense of grievance China feels about the historic division of their nation.

If China is united and strong now, and reveres Mao, it is because they feel they have only relatively recently been free of foreign occupation and exploitation itself. Too many in the west choose to ignore the hurt and pain in China’s past, and its own quest for security.

Boris Johnson, with one eye on trade and investment, sometimes declares himself a “Sinophile”; while Dominic Raab, in his time as foreign secretary, let slip that human rights were not in any case top of his agenda. Yet the overwhelming mood is of paranoid hostility to China, and the feeling is bound to be reciprocated in Beijing.

There is an important, parochial dimension to Aukus. Even if everything that was claimed about China’s supposedly malign intentions were true, and it is set on global dominion, it is still odd to see Britain – at best a middle-sized European power – trying to project its modest power halfway around the world. The debacle in Afghanistan is a reminder of the flaws in the special relationship with America.

Common sense and recent experience suggests that the UK’s principal interests remain in Europe, and the threat to national security – including state-orchestrated murders on British soil – emanates from the Kremlin. Under President Trump, it was plain that America’s commitment to Nato and Europe could easily become weaker than it was historically, or than it is now.

It is (in a way) heartening and reassuring that old friendships in the “Anglosphere” are being cultivated, but the further damage Aukus has inflicted on the Anglo-French partnership can hardly be dismissed. The real special relationship for most of the past 120 years for the UK has been with France.

“Global Britain” is a slogan and, at best, an aspiration. Britain as a European power is the established geopolitical reality.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

20Comments