Scottish independence now feels as far away as it has ever been

Editorial: There is simply no route available to the SNP now that the Labour leadership has rejected another referendum, and Mr Yousaf has no strategy to boost support for another vote

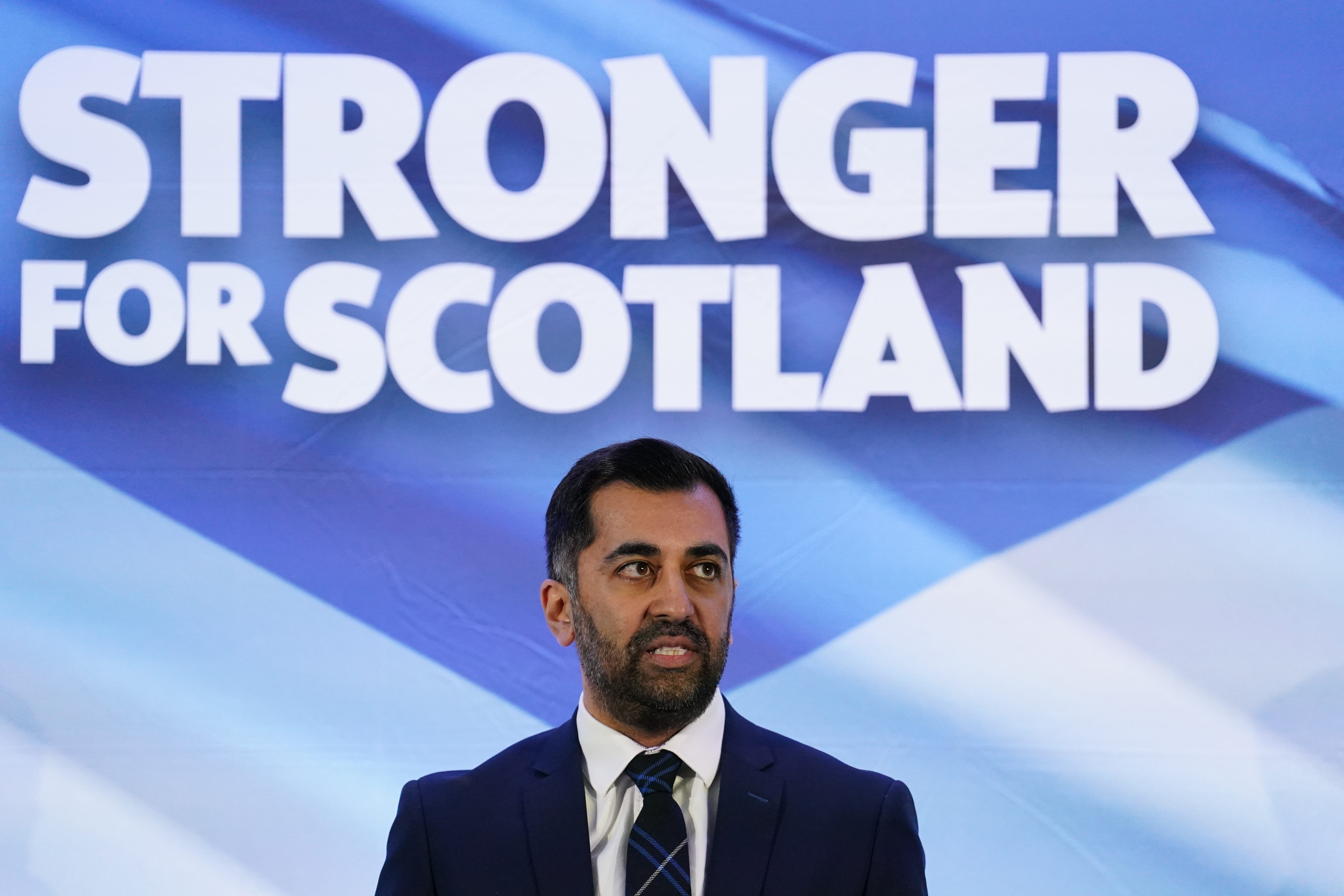

The new leader of the Scottish National Party, Humza Yousaf, declared himself “the luckiest man in the world” to lead the party he “loves so dearly”.

He certainly deserves to be proud of his achievement. At 37, he is the youngest first minister to be elected, the first from a minority ethnic background, and he has survived the most acrimonious leadership campaign in the party’s history. Even his political enemies will wish him well personally as he embarks on his new role.

However, while he may be personally fortunate, “lucky” is not the term that leaps to mind when surveying his inheritance and the task ahead. He has, in Nicola Sturgeon, a hard act to follow. She was just as divisive a figure as she conceded she had been when she announced her resignation; but no one could doubt she was a leader, and a combative one with it.

Over her eight years in office, she has seen off numerous of her Labour, Conservative and Liberal Democrat counterparts, and somehow found the confidence and energy to see off Alex Salmond.

For Mr Yousaf, the contrast is inevitably unflattering. Even his biggest fans couldn’t call the new SNP leader a fireball, ready to reignite the struggle for independence. His margin of victory over Kate Forbes – 52 per cent to 48 per cent – has an unhappy echo of the Brexit referendum, and cannot be taken as a ringing endorsement of his leadership. Rather, it reflects the mood of a party that finds itself divided and somewhat lost.

In truth, given Ms Forbes’s controversial views on personal morality, Mr Yousaf should have scored better among the SNP’s broadly progressive membership. That he did not means he will have to work hard to persuade his party’s supporters that he, the “no change” candidate, is going to move the party out of the doldrums.

Mr Yousaf also becomes first minister at an unfortunate moment in the electoral cycle. After the SNP’s almost 16 years in power, the mistakes, misjudgements and sheer fatigue were bound to build up, and so it has proved. On the NHS, schools, the economy, the ferry scandal, and lately its gender recognition policy, the party’s administration seems to have lost its way, become complacent, and grown out of touch with public opinion.

Mr Yousaf proudly declares that he has Ms Sturgeon “on speed dial” and will be in constant touch for advice and guidance. Mr Yousaf really does not need Ms Sturgeon, who is reportedly learning to drive, as his back-seat driver.

As the “continuity candidate” and a long-standing ally of Ms Sturgeon, he will find it difficult to make the changes in direction that Scotland needs and which might deliver yet another term of office for the SNP when the next Holyrood elections arrive in 2026.

As for the SNP’s raison d’etre, independence feels as far away as it has ever been in modern times. There is simply no route available to the SNP now that the Labour leadership has rejected another referendum, joining the Conservatives in adamantine refusal, and the UK Supreme Court is refusing to overturn the terms of the Scotland Act 1998.

The cynical attempt to use the Gender Recognition Reform Bill as a way to pick a fight with Westminster has backfired, and has actually set the cause of independence back among the Scottish public.

To this, Mr Yousaf has no answer. He rightly points out that pursuing a second referendum is foolish unless public opinion is firmly and consistently behind the idea, and it has not been for some time – leaving aside the period of Liz Truss’s premiership, when it sometimes felt that every part of the UK would rather like to leave the UK if it was to be governed so abysmally.

Mr Yousaf has no strategy to boost support for another vote, or to persuade the Scottish people that without “independence in Europe” Scotland cannot be free and prosperous. It has to be said that even the formidable Ms Sturgeon’s attempts to persuade them were floundering by the time she decided she’d had enough.

But that task now falls to Mr Yousaf, and he doesn’t seem that keen on it. A special conference on the path to independence will supposedly frame a fresh strategy; if the leadership contest is anything to go by, it will more likely to turn into a display of bitter divisions.

All that said, such is the continuing strength of the SNP that it remains the favourite to win any election held in the foreseeable future, but its previous hegemony is gone. The feeling of “time for a change” is powerful in any polity.

For a people who never consented to Brexit, or to a Conservative government, their most immediate opportunity to be rid of rule by English Tories is next year’s UK general election, and a vote for Labour – or, in a few cases, for the Liberal Democrats, where they have the best chance of taking a seat.

In that context of a mildly resurgent Scottish Labour Party, the best thing that Mr Yousaf can do is to take Ms Forbes’s advice, fix the public services, unite the party, and persuade the Scottish people that the SNP is about more than independence and the politics of grudge and grievance against Westminster. He’ll be needing some more luck.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments