Leave aside for a moment the morality of the government’s plan to remove asylum seekers to Rwanda. The first fact about the scheme is that it will not work. It is most unlikely to persuade the Supreme Court, which ruled against the scheme last month, that its legal defects have been remedied.

The second fact about the scheme is that it will not work. Even if the Supreme Court were persuaded, and a few planeloads of asylum seekers did arrive at Kigali International airport, after further months if not years of court cases concerning the specific circumstances of each individual, the policy would not act as enough of a deterrent to “stop the boats”.

The prime minister’s insouciance about the Supreme Court is surprising. For someone with such a reputation for attention to detail, it can only be concluded that he has not read the judgment in full. He should have been directed to paragraphs 19 to 26, in which the justices list the treaties which they believe would be broken by the scheme. Not just the Refugee Convention of 1951, but the United Nations Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment of 1984, the United Nations International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights of 1966, and the European Convention on Human Rights of 1953.

Conservative MPs of a radicalised Eurosceptic tendency who, having moved on from leaving the European Union to argue that Britain must repudiate the separate convention on human rights, need to raise their sights. They must also argue that Britain seeks changes to at least three other solemn and binding treaties – and that we must withdraw from them too if those changes are not made.

None of this is going to happen, which is why the government is seeking to deal with the issue that the Supreme Court ruled was in breach of those treaties: that asylum seekers removed to Rwanda would be at risk of being sent from there to a country where they would be subjected to persecution. James Cleverly and his predecessor as home secretary, Suella Braverman, think that today’s treaty with Rwanda provides guarantees that this will not happen.

Again, they and the prime minister have not read the Supreme Court’s judgment closely enough. It makes it unambiguously clear that the court does not regard the Rwandan government as a reliable partner in this enterprise. A treaty, even one which sets up a monitoring committee and an appeal body of international judges, is not going to change that fact.

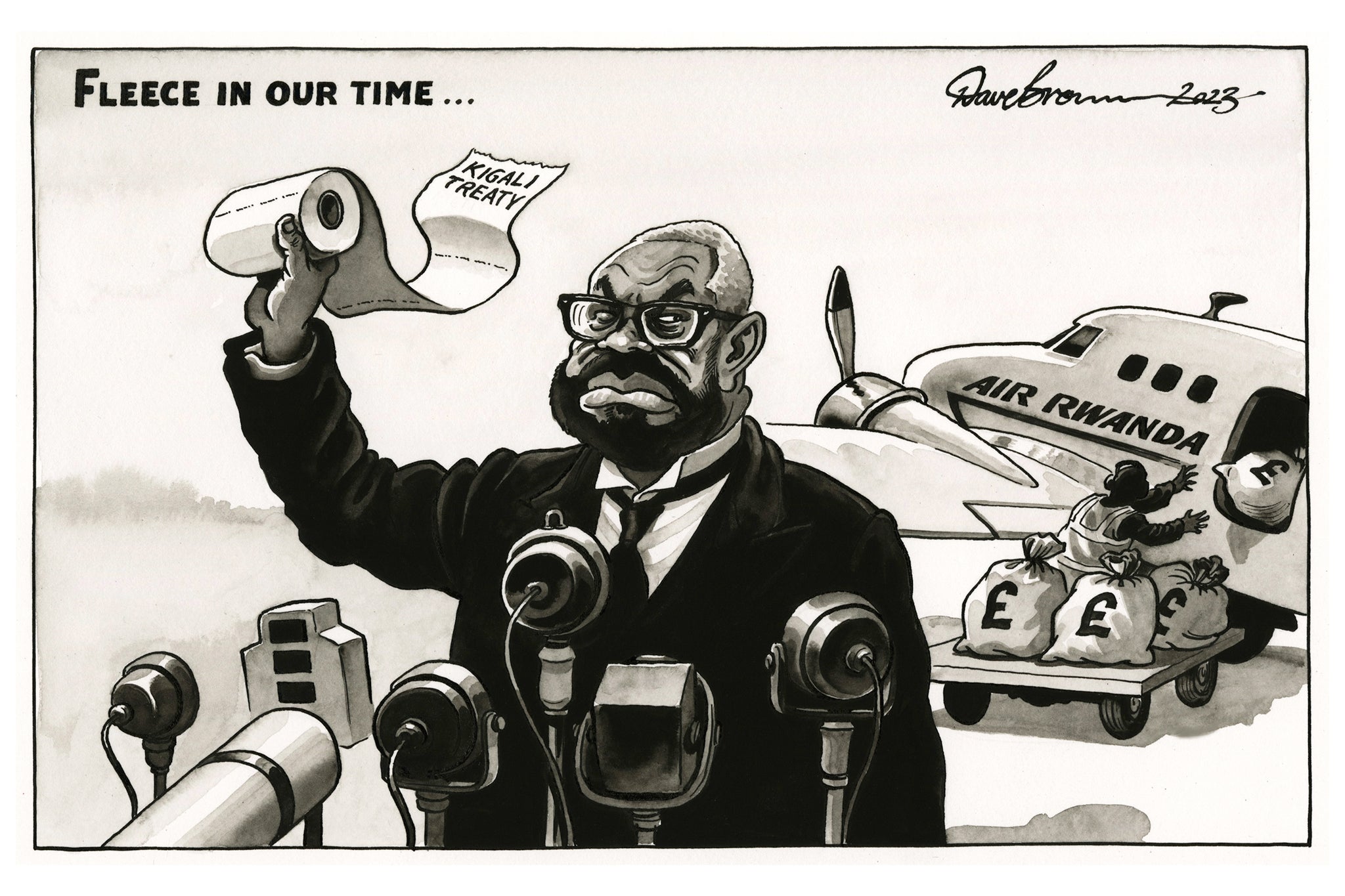

Mr Cleverly has flown 4,000 miles for a photo opportunity and a remote video appearance at this morning’s cabinet meeting that allows the government to pretend it is doing something, but which will not impress the Supreme Court.

And even if it did, the scheme would not work, in the sense that it would not stop the small boats coming across the Channel. It would “work”, in its own terms, only if those attempting the crossing knew that there was little chance that they would be allowed to stay in the UK. A couple of planes going to Rwanda, which does not have the capacity to take more than a few hundred people, is not going to be a big deterrent if, say, 30,000 people make the crossing this year.

The best prospect for a workable solution to the small boats problem remains one of negotiation with our European neighbours, in particular the French but with the European Union as a whole, most of whose members are struggling with similar problems on a larger scale. Mr Cleverly should be signing treaties in Paris and Brussels, not Kigali.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments