Rwanda is an absurd hill for a prime minister to die on

Editorial: Should his beleaguered immigration plans fail to make it through the House of Lords, Rishi Sunak would surely then go to the country to shore up support to ‘Get Rwanda Done’. It would be a lose-lose situation

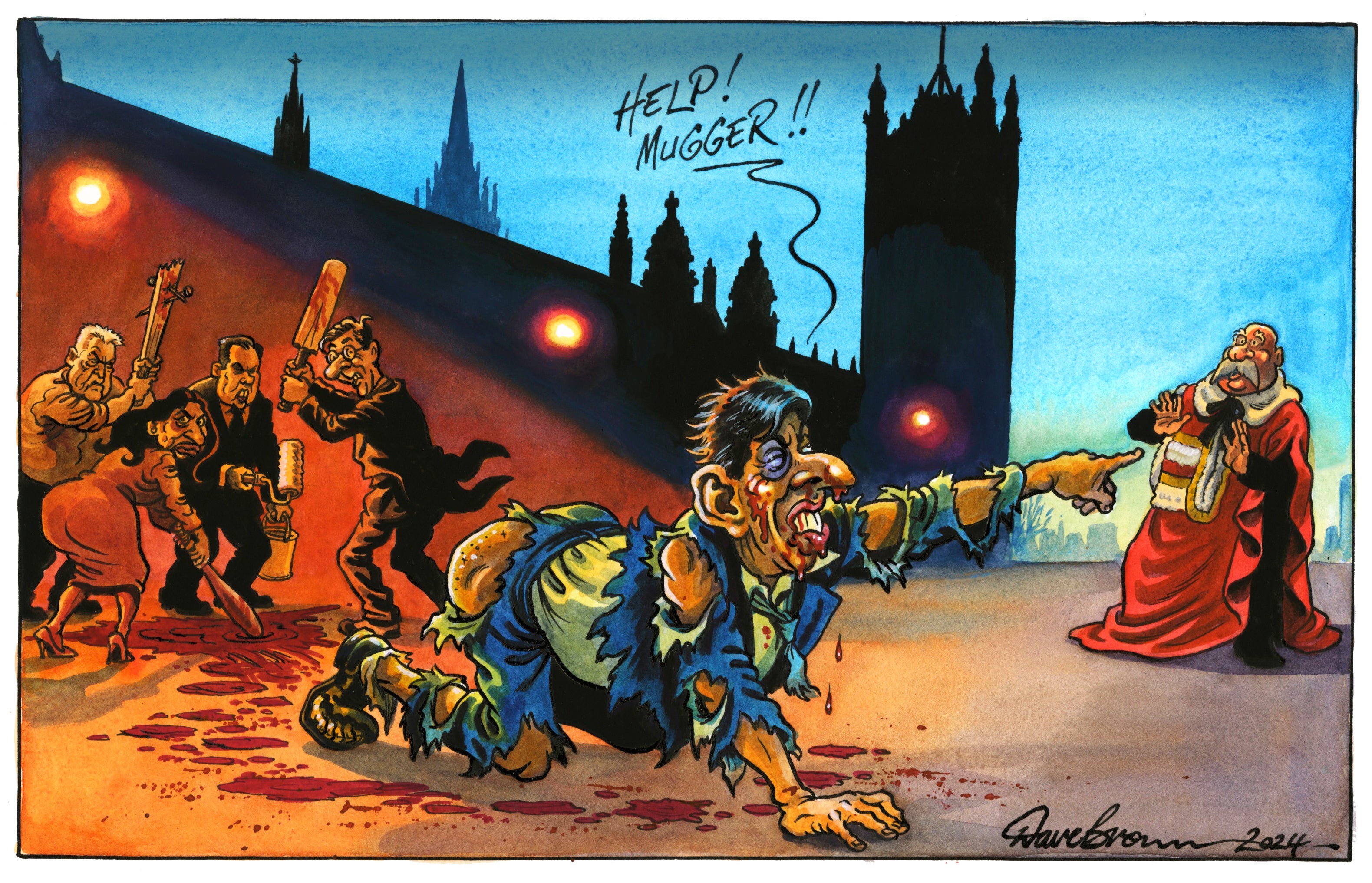

After surviving the latest skirmish with his hard-right MPs, who are clearly no longer the fearless Spartan force that once they were, the prime minister took to his podium at No 10 and made the most of winning what ought to have been a fairly routine vote on the latest Rwanda bill.

Rishi Sunak called on the august members of the House of Lords, to where the bill is now headed, to “get on board and do the right thing”.

Doing the “right thing” is very much in the unwritten constitutional remit of the noble peers, but they are not there to “get on board” with any scheme being pursued by any government. Mr Sunak pointedly referred to their “appointed” status, and advised them not to defy “the will of the people” as expressed by the democratically elected chamber.

Mr Sunak knows full well that there is trouble ahead in the Lords, which could possibly culminate in the effective loss of the Rwanda bill (and in further personal humiliation for him). He is thus getting his excuses in early, setting up the members of the second chamber as the anti-democratic villains of the piece – if not going so far as to label them the enemies of the people – simply for carrying out their constitutional duties.

In one sense, then, Mr Sunak is trying to establish himself in a win-win position. If the resistance in the Lords is eventually overcome, and the Commons and his government prevail, then one or two token planes filled with pitiful refugees might land in Rwanda before the general election. Mr Sunak will have his highly visible vindication, and he can claim, with no great evidence, that this terrifying deterrent is about to, at long last, “stop the boats”.

Alternatively, if the House of Lords puts up more of a fight, then Mr Sunak can blame it for blocking the policy and showing utter contempt for the British people. His policy would have failed, but it would not be the fault of the prime minister or his party; rather it could be blamed on the legislative arm of that amorphous liberal-elite blob, residing in some splendour in the scarlet and gilt upper chamber, where it is woefully out of touch with the red wall and the coastal communities that are supposedly subject to an unwelcome invasion.

In such circumstances, Mr Sunak could declare an intention to take his case to the country in a “Get Rwanda Done” general election, with a pledge to implement the plan and ignore international law.

Obviously, Mr Sunak would prefer to deport a symbolic consignment of refugees than engage in a war of attrition with the upper house, but either of those scenarios would suit him electorally. It would also create a useful “dividing line” with Labour, which has promised to abolish the Rwanda plan, calling it a “gimmick”.

The reality, however, is that Mr Sunak could find himself in something of a lose-lose situation. If the House of Lords continued to block the bill, then the prime minister would have to invoke the Parliament Act. The Rwanda bill would then become law – but only in the next session of parliament (when he would be unlikely still to be leader). Mr Sunak would be defeated and look like he was not in control, which he would not be. Not since the days of David Lloyd George has a government sought to win a general election on a “people versus peers” platform, and it is unlikely to be the basis for a Tory victory in 2024.

Contrariwise, if the bill is passed and the Rwanda plan is implemented, it is still unlikely to represent much of a deterrent because the scheme is so small, and the chances of deportation correspondingly minute. To the extent that it does constitute a deterrent, it will merely create a new problem of asylum seekers simply disappearing to avoid being sent to Rwanda – and there is some evidence that this process is already under way.

Similarly, rather than surrendering themselves to the authorities in the English Channel, they would be more likely to land on the south coast in clandestine fashion, and melt away undetected into the countryside. The boats, in other words, would not be stopped, and the government would “lose” thousands more people – a severe embarrassment. Once a person has been notified that a one-way ticket to Kigali has been booked for them, that person has a fairly easy choice to make.

The main impact of the Rwanda plan, a gimmick left over from the Johnson era that even Mr Sunak used to view warily, is not going to be felt by the refugees, who see it as a much smaller risk than drowning in the English Channel; nor will it be felt by the people-smugglers, who will regard it as a mild occupational hazard.

It is the British people who are increasingly viewing it as a distraction, and as irrelevant to the much larger number of immigrants arriving entirely legitimately under the points-based system by way of a work visa. More than anything, the Rwanda plan has become both a cause and a symbol of Tory division, of Mr Sunak’s struggle to remain in control of events – and not least, of his questionable sense of proportion. It is an absurd hill for the prime minister to die on.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments