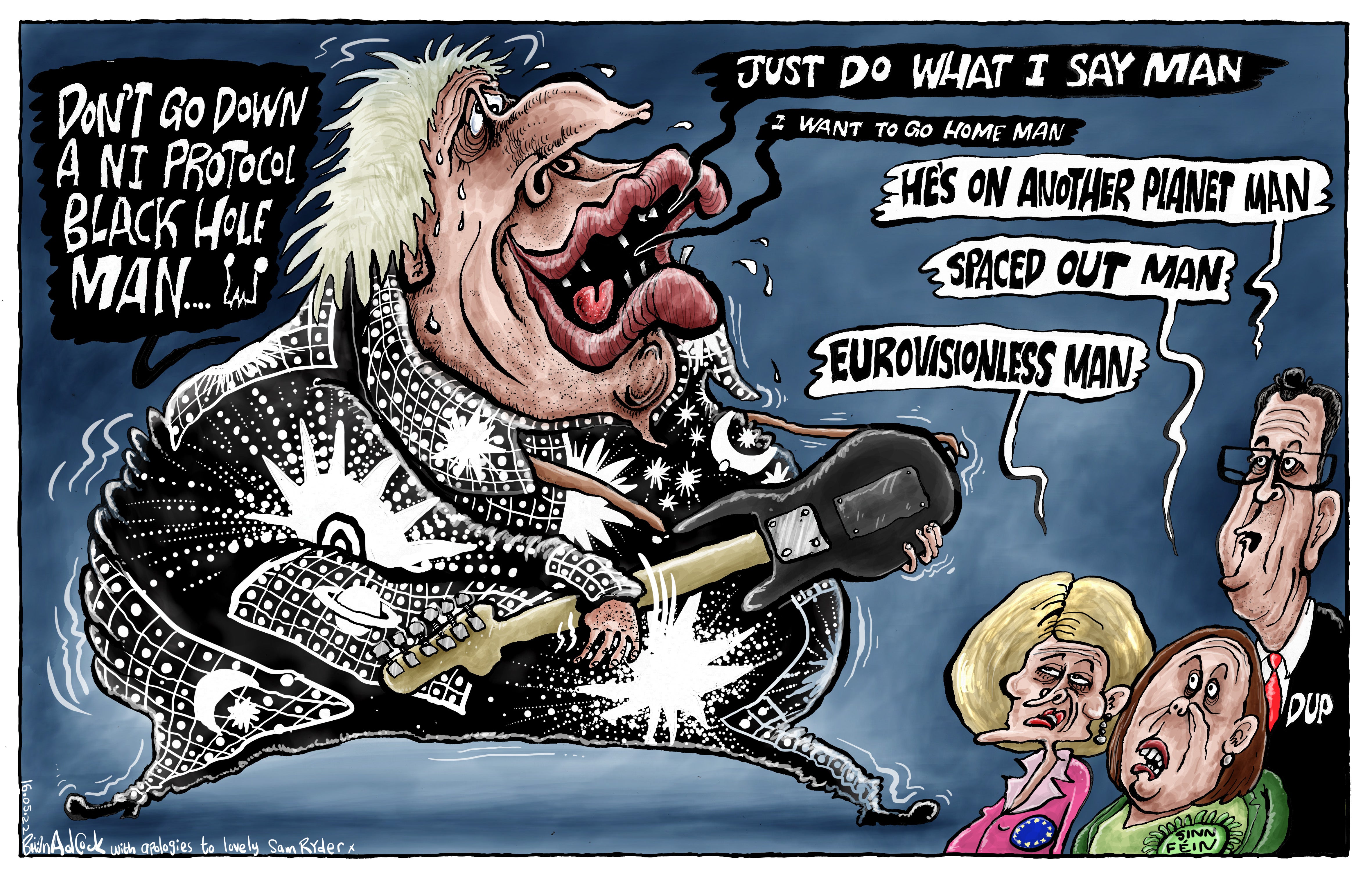

The PM is caught between Europe and Northern Ireland, in a trap of his own making

Editorial: Boris Johnson now finds himself as the unhappy filling in a ‘Europe Says No’ and ‘Northern Ireland Says No’ sandwich

Just as the warm Eurovision applause for Sam Ryder dies down, the government will renew its confrontation with the European Union. Far from “getting Brexit done” in 2019, it seems to have become a permanent embarrassment and a weeping diplomatic sore – a sort of cold war. Surely this is not the Brexit anyone voted for?

This week, the foreign secretary will publish legislation designed to allow Britain to break an international treaty. Helpfully, the attorney general, Suella Braverman, has reversed the advice of her predecessor, Sir Geoffrey Cox, and advised that such a unilateral move would be lawful. This, of course, does not make it lawful; still less does it make it wise.

The threat is designed to strike such fear into the hearts and minds of the EU that it will simply decide to pretend, in effect, that it doesn’t need a trade border with the UK at all, and that its single market will be fine, just as the British government is pretending that the Northern Ireland protocol is a problem that can be solved by ignoring it. It is a kind of Alice in Wonderland proposition: that if we all stop thinking about the Irish border, it will disappear.

The draft legislation – which will in any case be subject to delays in the Lords, and legal challenges – is supposed to function like the nuclear deterrent: its very presence ensuring that it never has to be used. However, the record suggests that if the EU calls Britain’s bluff by threatening a devastating trade war, then Britain will simply cave in. There is no reason to think anything will be different this time.

Going by its Eurovision performance, the UK is enjoying some goodwill over its support for Ukraine and for the EU’s Nordic, Baltic and eastern states; but that doesn’t solve the problem of where to put the Irish (ie EU) border with the UK. The British proposal to take it out of the Irish Sea simply means it has to be plonked somewhere else – either on the island of Ireland, or between Ireland and the EU. Neither of these options would constitute a practical alternative to the existing arrangements, unsatisfactory as they are.

Against such a backdrop, Boris Johnson will travel to Belfast to try to persuade the Democratic Unionists to re-engage with the power-sharing executive. Yet there seems little incentive for them to do so.

To keep up to speed with all the latest opinions and comment, sign up to our free weekly Voices Dispatches newsletter by clicking here

Jeffrey Donaldson and his colleagues might well suggest to the prime minister that, by holding the assembly and the executive hostage, they are strengthening his bargaining hand, given that the instability in the province is supposedly the fault of the protocol (as opposed to being the result of Brexit and the deal Mr Johnson signed).

In any event, they see no pressing reason to serve with Sinn Fein in a new government, and having been duped before, would be disinclined to trust the prime minister. After all, he once told the DUP that there would be a trade border down the Irish Sea “over my dead body”.

Mr Johnson now finds himself as the unhappy filling in a “Europe Says No” and “Northern Ireland Says No” sandwich. As the architect of his own misfortune, it’s hard to feel sorry for him.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments