A little more than 24 hours after she told the House of Commons that “I’m a fighter and not a quitter”, Liz Truss executed the ultimate U-turn – and quit. It was a painfully ironic end to a painfully difficult time in office.

By the end of it, she will have been prime minister for just short of two months, the shortest span in history. Ms Truss has carved her name into the history books for many reasons, none of them good. She said in her resignation speech that she could not deliver her vision of a low-tax, high-growth economy. True.

She did not add that it was undeliverable because the policy didn’t work, and she left hanging in the air the impression that timorous colleagues, the “mainstream media”, the establishment and the absurdly confected “anti-growth alliance” had sabotaged her brilliant plan. International capital markets delivered the final blow, and they are neither woke nor working in concert. Traders in Singapore, Wall Street and London for that matter have no interest in Liz Truss as a leader, only in the creditworthiness of the United Kingdom and making money.

The stark truth should have been acknowledged, even though it might be too much to expect her to admit it. The dash for growth was inflationary and would have wrecked the public finances. The market reaction merely reflected those facts, and that is why she and Kwasi Kwarteng had to abandon their mini-Budget, the damage to the UK’s reputation done. There was no conspiracy; merely mistakes.

The 45 days Ms Truss has served thus far as premier have certainly been eventful. In some respects, she managed to ram the usual quota of excitements and embarrassments seen in a standard four-year term of office into just a few weeks – resignations, sackings, insults, blank stares, uneasy pauses, splits, plots and open dissent, votes of confidence and U-turns. There was never a dull moment, and that is why she had to stand down. She was a “disruptor” when a period of calm rebuilding was needed.

Who’s next?

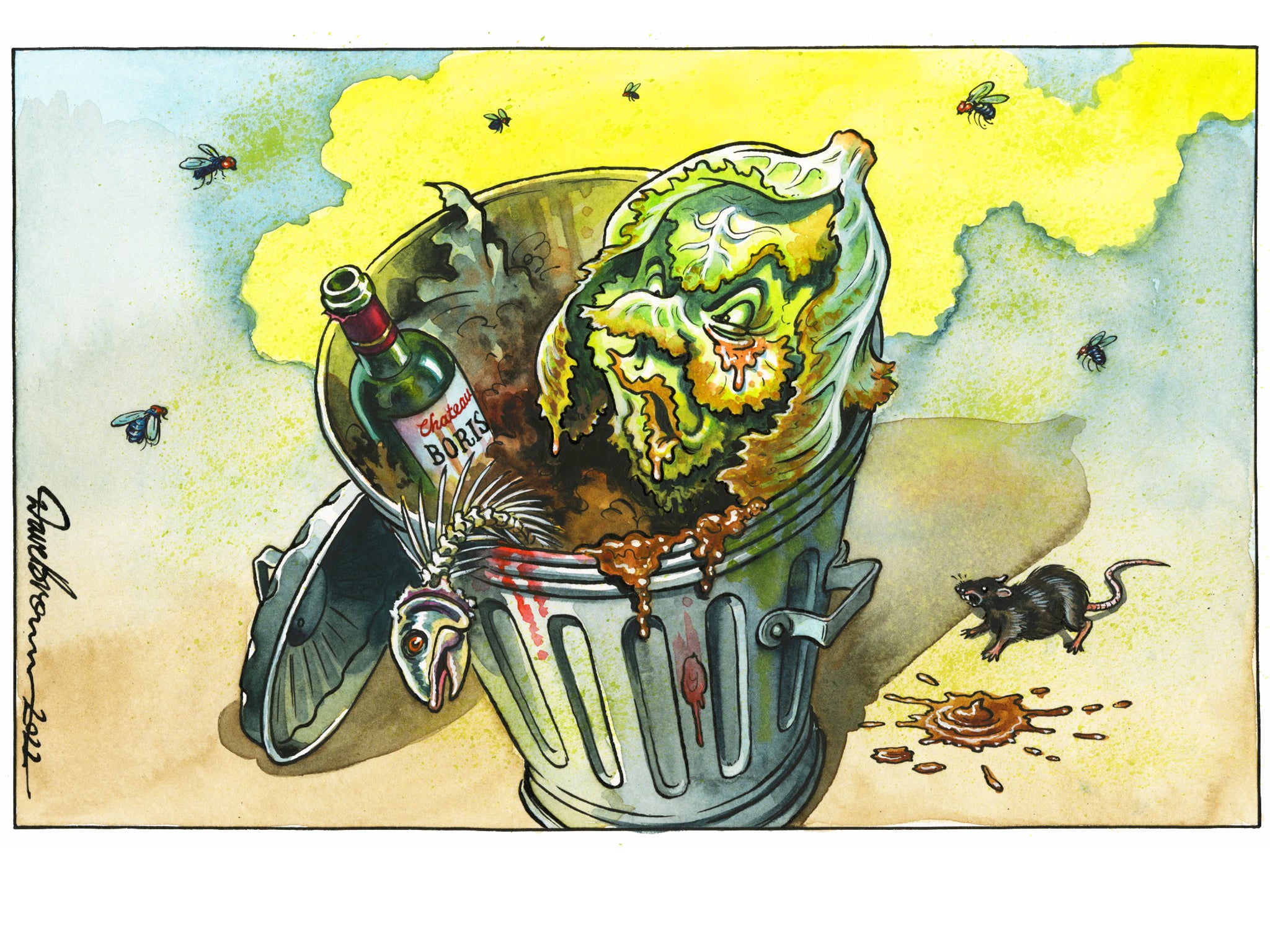

In principle, there is nothing to prevent Boris Johnson from attempting the biggest comeback since Lazarus, or at least Jeremy Hunt. If he makes it to the final two and Conservative Party members are allowed to make the final choice again, Mr Johnson would probably beat any of the likely rivals, though Penny Mordaunt would give him the best run for his money. Yet it is difficult to see how he would be able to do the job in the aftermath of the persistent law-breaking known as Partygate and various wither scandals.

Boris Johnson still faces investigation by a Commons committee into whether he lied to parliament. He would be badly distracted, to say the least, and reviled by many in the party. Nor is he any longer the election-winning machine he was in 2016 and 2019; but many cling to the notion that he can rebuild the coalition of voters assembled three years ago.

If the last few weeks have taught us anything, it is that politics is a strange, unpredictable business; and that conventions and rules are there to be broken (something Boris Johnson understands all too well). He is taking soundings, but it is possible that he is merely toying with his party and teasing the electorate, as is his habit.

Rishi Sunak is reportedly “certain” to stand, and Penny Mordaunt is also likely up for the fight again. So, perhaps, will Kemi Badenoch, popular with the grassroots, and Suella Braverman’s vaulting ambition has been blatantly on display for some months now. As with Johnson and Badenoch, Braverman’s best hopes lie within the party membership. Like Truss, she will promise them the impossible.

To keep up to speed with all the latest opinions and comment, sign up to our free weekly Voices Dispatches newsletter by clicking here

At the end of the process, it is quite possible that the party membership will, once again, choose a new leader and prime minister that does not command the fullest confidence of Conservative MPs, and therefore will have to manage some of the same tensions that brought Liz Truss down.

A new leader, working closely with Jeremy Hunt as chancellor, may be able to put the public finances firmly on a sustainable footing and reassure the capital markets. That, however, implies a recession next year, a further squeeze on living standards and public services, and much hardship. There won’t be much “levelling up” nor hope around during the fight against inflation.

The fact is that the Conservatives are exhausted, and the mandate Boris Johnson won in December 2019 is now dissipated and irrelevant. The public did not vote for the policies now being pursued, and once again they are reduced to the status of observers as a tiny group of Conservative members once again try to foist some hard-right policies on everyone else. It’s grotesque.

Hard as it may be to believe after the last few months, the Tories could yet do more harm, and they could still grow more unpopular than they are today. Sooner or later they will have to account for themselves to the electorate, and that moment should be as soon as the new leader is elected and a general election can be held. Strange to say, that is probably most likely under Boris Johnson, still one of life’s chancers, seeking to break the impasse as he did in 2019. The year 2022 may yet spring some more surprises.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments