There is an old Westminster adage that a Budget that looks good on the day will look terrible in the morning, and Jeremy Hunt’s first (formal) effort as chancellor looks to be conforming to the saying, at least to some extent.

In contrast to Mr Hunt’s first efforts last year, which rescued the public finances after the disastrous Truss-Kwarteng dash for growth, and have stood the test of time well, his latest package has raised almost as many questions as it has answered. Mr Hunt and his colleagues would do well to address them sooner rather than later.

The most troublesome looks to be the reform to the size of pension pots individuals are allowed to amass over their lifetimes. Once there was no limit at all. But, more than a decade ago, George Osborne, as chancellor, ruled that the generous tax reliefs available to those wealthy enough to be in that position should be capped when the value of the funds reached about £1m.

As ever, that rule came to have unintended consequences when senior NHS doctors, in particular, found that the loss of that tax perk blunted their incentive to work. It has been one powerful reason why so many GPs have reduced their hours or retired early, creating a shortage of capacity in primary care and the madness of the 8am telephonic “fastest fingers first” scramble for an appointment.

Mr Hunt boldly took Labour’s previous advice, proffered by Wes Streeting, and abolished the cap. Yet now Labour complains that it is a tax cut for the very rich, at a time when many are struggling with the cost of living. What’s more, the cost to the taxpayer of correcting the situation may run to something like £40,000 to £60,000 per doctor per year, depending on which estimate of the number of doctors affected is taken – which seems absurd, if not obscene.

What looked to be a sensible, swift and well-intentioned solution to overlong GP waiting times and a shortage of experienced clinicians looks instead to be a gratuitous “bung” to the wealthiest in society. Suddenly, Mr Hunt looks less like a benign house doctor manque, and more like a Robin Hood in reverse. The embarrassment follows a sensitive juncture which has seen ministers working to settle the pay dispute with nurses and paramedics (whose entire salary would be less than the average senior doctor’s proposed new annual tax break) – a move which, at last, seems to be approaching a compromise.

Assuming that senior doctors should be treated as a special case among high earners, it is a fiendishly difficult task to create a tax loophole, for want of a better term, tailored to that group alone, especially if it is to be implemented around the established rules of the NHS pension scheme. Yet, if the principle is still judged to be sound, then the fiendishly clever people in the Treasury will have to find a better way of achieving what the government, the opposition and the public all want, which is to straighten out this disincentive and retain the most experienced doctors in the system at a moment when they are needed as never before in peacetime.

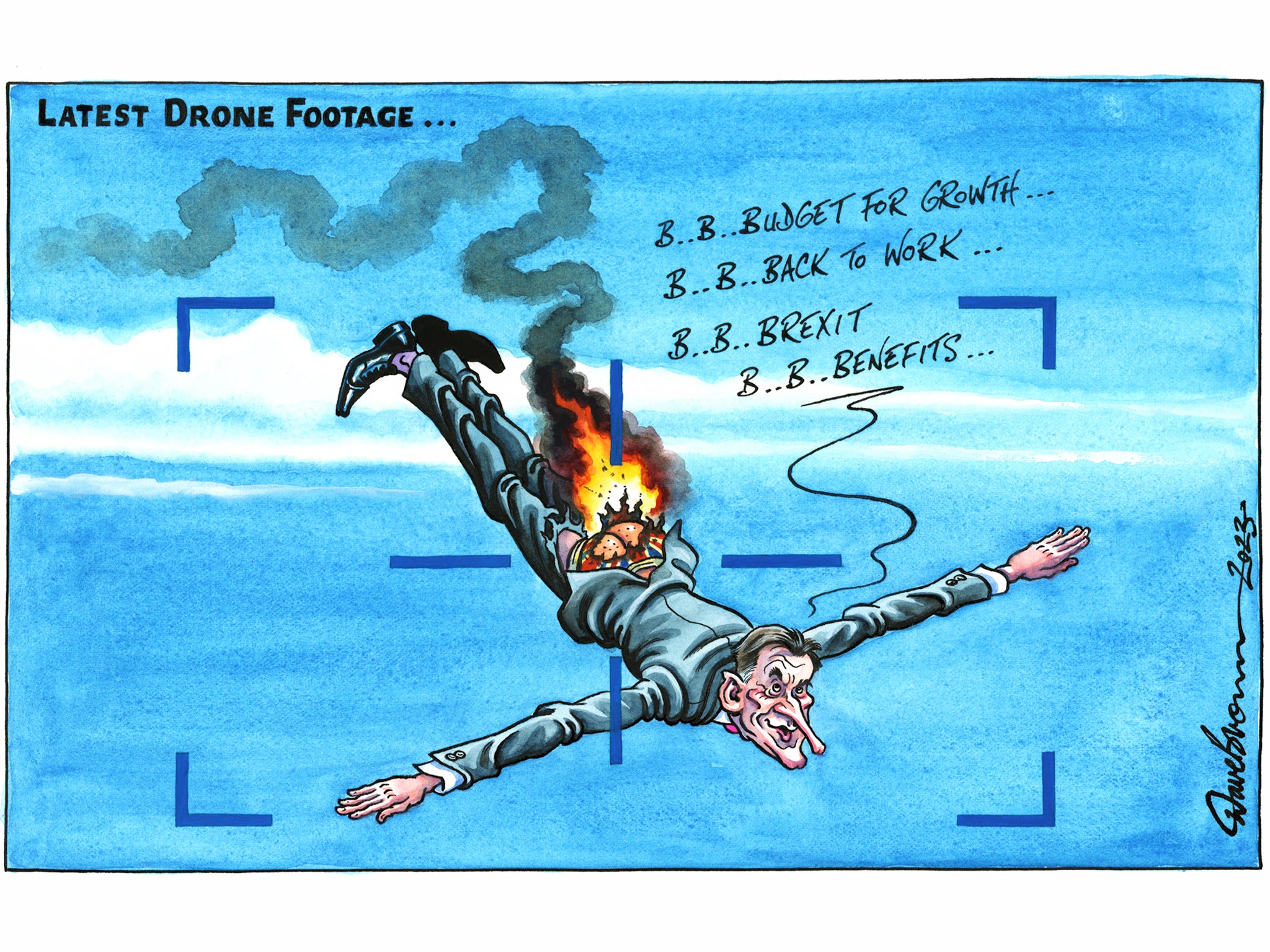

Mr Hunt should feel no embarrassment if he has to amend his plans, if the goal is a noble one – and may make a saving into the bargain. As Budget gaffes go, it is nowhere near the level of, for example, the “pasty tax” that helped reduce Mr Osborne’s 2012 Budget into such a memorable “omnishambles”. That was the most capricious example in recent times of a Budget unravelling in rapid and spectacular fashion.

Childcare was, though, to be the proudest reform framed by Mr Hunt, and here the criticism that has arisen overnight has been of a different nature, both less damning and less fair. Mr Hunt’s move was radical and widely welcomed, not least by the shadow chancellor, Rachel Reeves, and the shadow education secretary, Bridget Phillipson, who placed just such a reform at the centre of their own programme for government.

In this case, the criticisms from lobby groups are that Mr Hunt seems not to be going fast enough and far enough, and that he has underestimated the costs of making the new scheme work. That may be so, but Mr Hunt has to work within the tight fiscal constraints dictated not by dogma but by the UK’s substantial debt overhang after the energy crisis, the pandemic and, further back, the global financial crisis.

Mr Hunt’s aims and objectives are more or less identical to Labour’s, and there is just the suspicion here that, were Ms Reeves delivering her first reforming Budget, her package would bear a close resemblance to that put forward by Mr Hunt. To be fair to her, Ms Reeves admits as much. If a few billion more will be required to make the childcare reforms work, they can be found without too much disruption (for example by uprating fuel duty by inflation for the first time in a decade). As to speed, this is such a major change it is right to phase it in; indeed, with the shortage of nursery staff that is probably inevitable in any case.

Given such second thoughts on some of the important details, Mr Hunt’s package remains the solid piece of work it was intended to be. It could not disguise the continuing grievous damage inflicted by Brexit, including the biggest fall in living standards in modern history, and a decade of anaemic economic growth ahead.

The context for the Budget was always making the best of a bad job, and making the most of the limited choices available. Mr Hunt, at least on his own terms and in his own phrase, remains “on track”.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments