The tragic loss of life in the Channel, in the most horrendous circumstances, has promoted an outpouring of concern for those who have died, and for the plight of those rescued in a superlative effort by combined British and French forces.

The capsized vessel, so typical of the type used by desperate refugees seeking shelter in Britain, was also typical of those used so cynically by the people smugglers – flimsy, overcrowded, unseaworthy and, indeed, an accident waiting to happen. All are shocked by the incident, but no one is very surprised. Despite all the calls for action and prime ministerial plans that come and go, it has happened before, and it sadly will happen again.

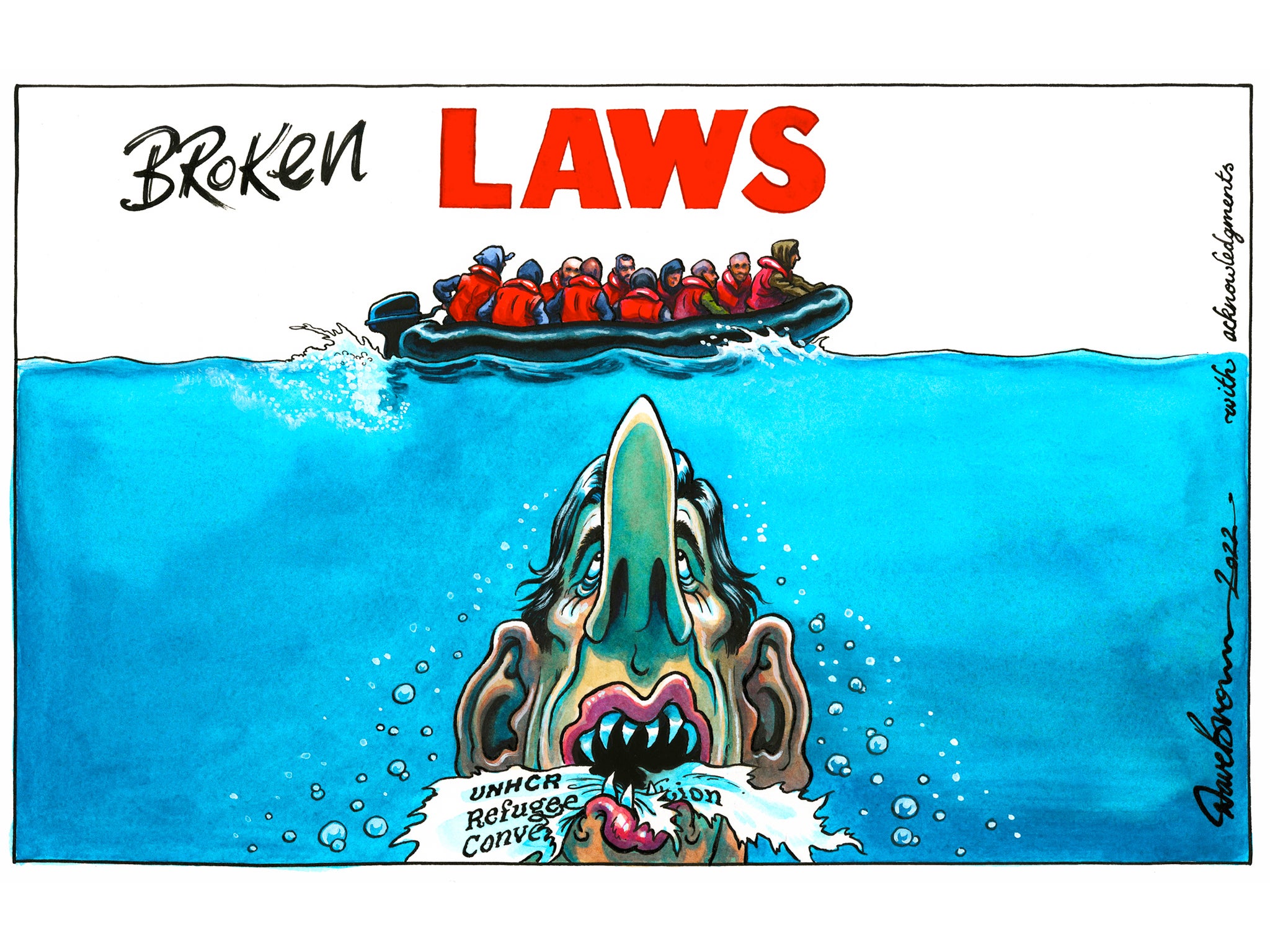

It is, then, at moments such as these that people are reminded of the human cost of the refugee crisis. These are fellow human beings who have lost their lives, almost drowned or died of hypothermia. They are not, to quote the dehumanising terms that have insinuated themselves into the debate, “illegals”, “invaders” or a “problem”; they have human rights, including the absolute right to seek asylum and the right to life.

Sometimes ministers talk about trying to dissuade the refugees from making these dangerous journeys by creating “deterrents”, such as the notorious, expensive and unlawful Rwanda scheme. The fact that some 40,000 people have risked their lives to reach the English coast this year alone proves what a nonsense of an approach that is, even if it had any moral respectability attached to it.

Desperate people are prepared to lose their lives to make the journey – surely the ultimate deterrent. It is often suggested that these refugees from war, terror and poverty cross seas and continents just to take advantage of the UK benefits system. It is time that obscene lie was nailed.

Rishi Sunak says he has a five-point plan to deal with the Channel crossings, but this tragedy highlights just how futile it will prove to be. Mr Sunak says that more “legal” and orderly routes to gain asylum will be made available, in concert with the UN High Commissioner for Refugees. The question then arises as to why so few routes exist, after 12 years of Conservative-led government, and – because this is not primarily a partisan matter – the Labour government before 2010, and the Major government before that.

The refugee crisis is hardly new, and has been a national disgrace for almost three decades. There is a pattern that has developed over this time, of global instabilities and wars – often instigated by the West – creating flows of humanity not seen since the Second World War; and an abject refusal to create an intentional framework to deal with it, or to devote sufficient resources to deal with claims and rehabilitate those few accepted for settlement.

It is a harsh truth that under Mr Sunak’s plan to limit asylum by quota to a few – as yet unspecified – selected "safe" routes, none of those rescued in the English Channel would be able to claim asylum in the UK, however well-founded their claim is. After they’d been discharged from hospital they would either be sent “home” (even where that amounts to a pile of rubble in Aleppo), or to a safe third country (again on the heroic assumption that places like Rwanda can be found to take the numbers that are now crossing the Channel). It is not a policy that sits comfortably with recent events in the English Channel.

As the Archbishop of Canterbury, Justin Welby, comments, these events highlight the fact that debates about asylum seekers “are not about statistics, but precious human lives”.

The shock of the deaths in the Channel may prompt some Conservatives to think more radically about what has gone wrong. Passing ever more stringent laws and treating refugees ever more harshly hasn’t worked, and is unlikely to do so in the future.

David Simmonds MP, more knowledgeable and experienced than most in the field, suggests more opportunities to claim asylum on the French side of the Channel, and he recognises, as too few do, that Home Office statistics show that the clear majority of people arriving via small boats are likely to be refugees fleeing war, conflict, and persecution.

There seems to be some common sense being applied at last. The prime minister’s pledge to create more safe routes, though inadequate as yet in scale, suggests that there is some dawning realisation at the top of government that “getting tough” on vulnerable people is usually counterproductive – and costs lives.

Suella Braverman, it must be said, is not an ideal candidate to lead fresh thinking, which is presumably why Mr Sunak himself has taken charge of the policy and set himself such exacting targets to clear the backlog of applications. A UK safe routes policy would attract a huge number of applicants and would force a debate on how many people the UK wants to accept – a fundamental issue usually ignored.

For a change, we will be invited to learn their names, get to know a little about what they were like and see what their hopes and dreams were. We will discover that they are not so very different to anyone else, just very much less fortunate.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments