It was not a great day for Boris Johnson; indeed, in a way, it was the worst since he was forced to resign last year. Any remote hopes that he might somehow make the biggest comeback since Lazarus and replace Rishi Sunak as prime minister were left shattered on the floor of the Grimond Room of parliament’s Portcullis House.

Even if Mr Sunak managed to lose every single Conservative seat in the May local elections, crashing the economy along the way, his party would not turn to Mr Johnson as a saviour.

Indeed, Mr Johnson looks increasingly likely to be sanctioned by the House of Commons committee of privileges, and is facing the possibility of a recall petition and a by-election in his seat of Uxbridge and South Ruislip. He looks finished, haunted even, as the truth catches up with him.

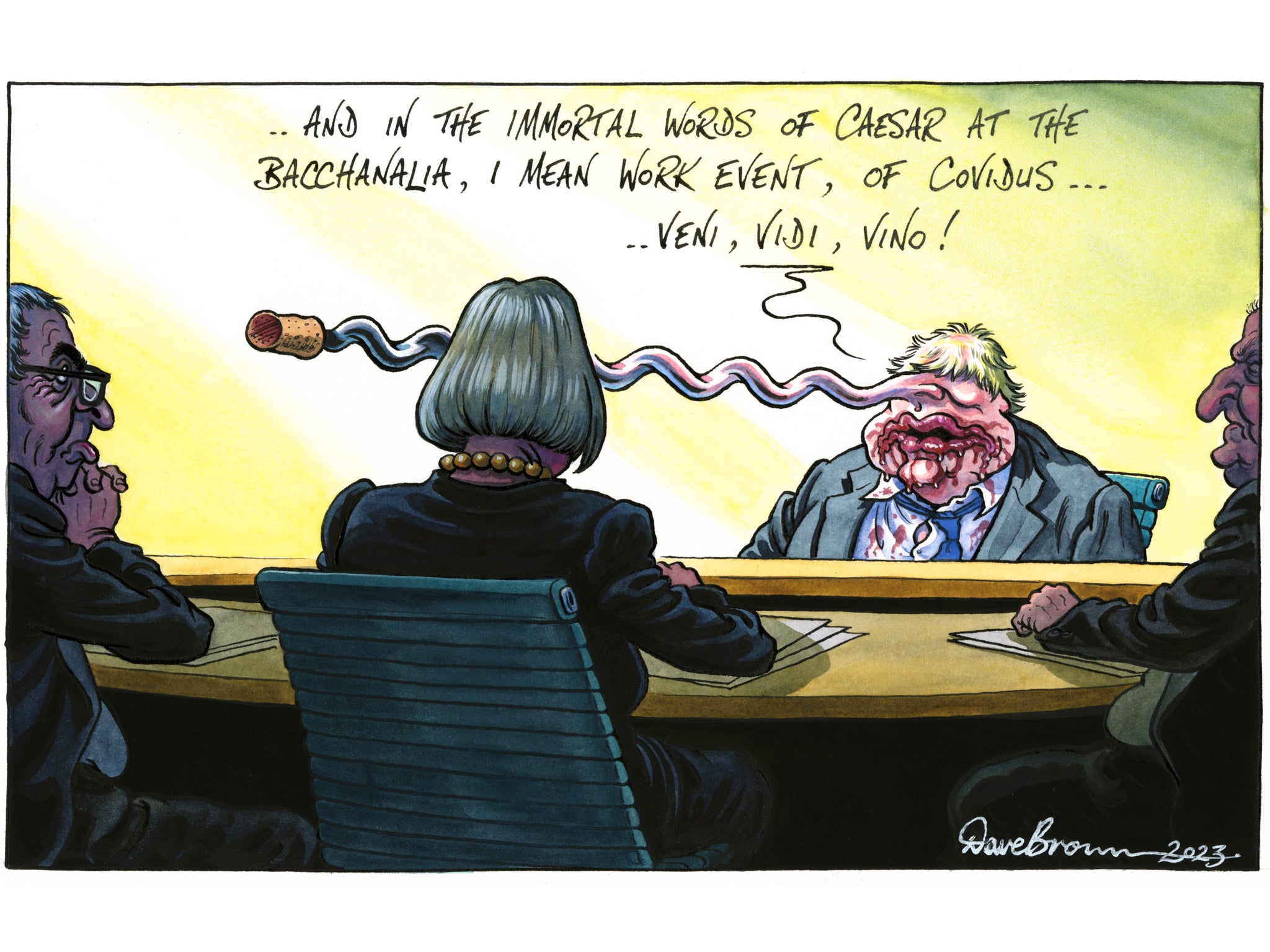

Mr Johnson’s performance in front of the committee was at best unconvincing. By turns tetchy, testy, arrogant, angry and rattled, waving his fist about and interrupting his questioners, his appearance served as a reminder that, for all his flair as a campaigner, he is unfit to hold high office. Humility is admittedly not his style, but he couldn’t even bring himself to utter a few tokenistic words of sympathy to all the victims of the pandemic who felt so grievously let down by his behaviour.

Time and again Johnson tried, and failed, to obfuscate, bluster and bluff his way past patient and forensic questions from the committee, which was ably chaired by Harriet Harman. It was parliamentary scrutiny at its very best, with none of the bias of a “kangaroo court”, as some of Mr Johnson’s outriders have claimed it to be.

Sir Bernard Jenkin was especially effective in focusing in on the essence of the inquiry, which is testing the likely truth of the various statements Mr Johnson made to the Commons. After one Johnsonian fusillade of excuses about the cramped conditions, the tired staff, and the belief that obviously social gatherings were “work events”, Sir Bernard advised him that if he had explained all that to the House of Commons at the appropriate time, he would not have had to sit for 3 hours and 20 minutes answering questions about whether he had lied.

Alberto Costa asked Mr Johnson why he had relied on junior political appointments to give him “repeated assurances” about following guidance and rules at all times rather than asking the cabinet secretary, Simon Case; no adequate reply was given.

Allan Dorans reminded the prime minister that every time he went up to his flat, he could see directly into the rooms in which the parties were taking place. Charles Walker took him to task for trying to undermine the committee; Mr Johnson refused to commit to accepting the members’ findings in good faith when they are published.

The humiliations heaped on Mr Johnson were relieved only by brief adjournments for votes. During one such break, Mr Johnson took himself off to vote against the government on the Windsor Framework. Perhaps Mr Johnson thought the result might act as an extra show of strength; a tangible, if informal, expression of support for him among the parliamentary party. Yet a mere 22 Tory backbenchers voted against the current prime minister’s improved version of the deal Mr Johnson negotiated, so it was more a show of weakness than anything else.

The country, through long exposure, has become too inured to the appalling excesses of Mr Johnson. It is obvious, as it was when the Partygate allegations first emerged, that Mr Johnson never took the coronavirus, or measures such as social distancing, seriously, despite almost dying of Covid.

As Sue Gray found, many of the staff in Downing Street and the Cabinet Office naturally adopted Mr Johnson’s carefree insouciance about the rules, which is how and why the rule-breaking was so endemic. No one told him things were happening that shouldn’t be, because Mr Johnson gave every indication that he didn’t mind. Had, say, Theresa May walked in on one of those impromptu gatherings, she’d have turned on her kitten heels and ordered the miscreants to get back to work.

We should also remind ourselves that his appearance before the privileges committee was historic, and not in a good way. It is the first time a former prime minister has been compelled to take part in such a hearing to convince his fellow parliamentarians he is not an out-and-out liar.

In the past, suspicions of this kind about any minister, even if they had inadvertently misled the House, would spell an honourable exit as an MP. Not for Mr Johnson. Even when Ms Harman offered him the opportunity to correct a previous, inaccurate correction to the parliamentary record, he petulantly threw it back. At a moment when he might have started to repair his reputation, he instead doubled down – and in doing so, he let the country down.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments