Boris Johnson’s Covid candour leaves Rishi Sunak looking shifty

The current prime minister has enjoyed a high reputation among the public for his self-evident compassion. Will it survive his predecessor’s inquiry testimony?

One group of people has been unfairly, indeed unforgivably, neglected in the current wrangling about government WhatsApp messages and diaries during the pandemic. They are the many hundreds of thousands, if not millions, bereaved as a result of the coronavirus, or else still suffering from the effects of long Covid.

The arguments have been legalistic, political, bureaucratic, technical – and conducted entirely within a sort of bubble.

Behind the lofty debates about precedent, collective responsibility, and the merits of a judicial review, however, lie thinly camouflaged attempts to protect vested interests and political careers.

Collectively, the establishment is letting the victims of the pandemic down. The human dimension has been all too readily forgotten in the scramble to gain control over the evidence that Baroness Hallett’s inquiry team need to do their job.

Disappointingly, this also pertains to the prime minister.

Rishi Sunak, despite his protestations, has not lived up to his famous pledge, delivered last October on his first day in office, that “integrity, professionalism and accountability” would be the guiding principles of his administration.

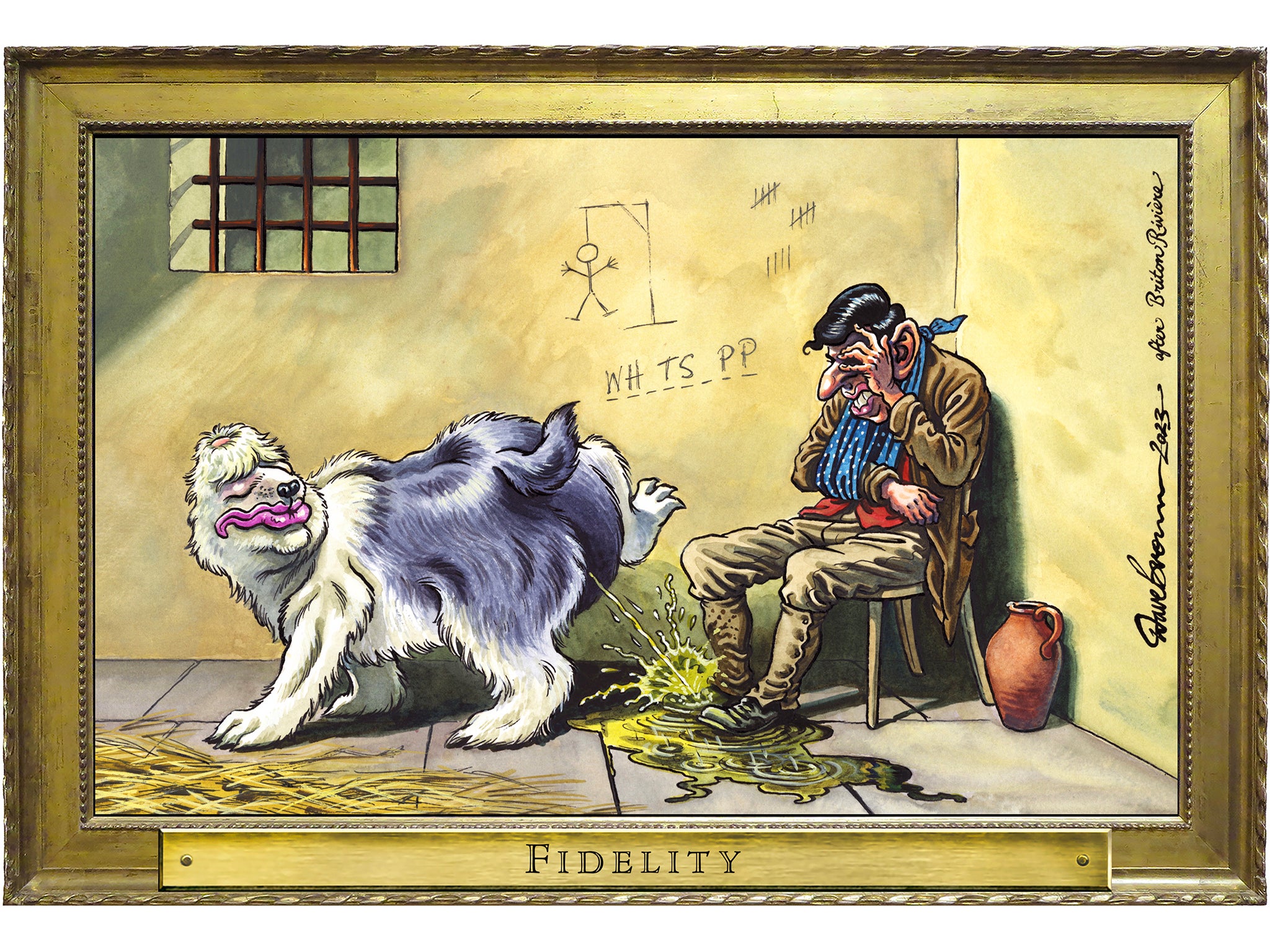

Indeed, extraordinarily, he has been outflanked morally by his predecessor, Boris Johnson, a man who has turned dissembling into an art form.

Mr Johnson is now, or so he claims, going to send as much as he can of the evidence he still holds directly to the Covid-19 inquiry.

In a pointed reference to Mr Sunak’s attempt to use a judicial review to suppress parts of the evidence bundle, Mr Johnson wrote in his letter to Lady Hallett: “The government yesterday decided to take legal action. It was not my decision to do so. While I understand the government’s position, I am not willing to let my material become a test case for others when I am perfectly content for the inquiry to see it.”

And so the spotlight alights on Mr Sunak, as it is he who now looks as if he has something to hide, even if he hasn’t. The impression of shiftiness is doing his reputation no good at all.

As our pandemic chancellor, Mr Sunak has difficult questions to answer, as have Mr Johnson and Matt Hancock (who has already, if unintentionally, allowed his own WhatsApp conversations to end up in the public domain).

In February, Lady Hallett sent Mr Johnson a list of no fewer than 150 questions about his response to the emergency, which will be answered in due course in written form, subject to cross-examination.

Soon, if it has not happened already, Mr Sunak will be confronted with a similarly long list of questions relating to his policies and behaviour during the crisis. We have a shrewd idea of what some of them will be.

As chancellor, for example, did he try to defy or weaken the effect of scientific advice to instigate a lockdown, fearing it would plunge the economy into a slump? Did he resist the imposition of social distancing at key stages in the pandemic? Did he, to put it crudely, put money ahead of human life? Did he really “follow the science”? If not, why not?

Particular attention will be paid to Mr Sunak’s pet “Eat Out to Help Out” scheme, under which diners were offered a modest subsidy to help revive the hospitality sector. At the time, some prominent scientific experts expressed concerns about the scheme being premature and risking an increase in Covid infections.

It would be interesting to learn what Professor Sir Chris Whitty and Sir Patrick Vallance were advising him at the time about such concerns. We already know that the permanent secretary to the Treasury, as accounting officer for the department, required Mr Sunak to issue an unusual “ministerial direction”, so concerned was he that the scheme was a waste of public money.

Mr Sunak at the time enjoyed a high reputation among the public for his self-evident compassion, his willingness to “do whatever it takes” to protect lives and livelihoods, by way of the furlough and other schemes, and his clear grip on policy and data (in stark contrast to the bumbling Mr Johnson).

Of all the ministers involved, Mr Sunak emerged with his reputation enhanced. Even though he was issued with a fixed penalty notice for attending a gathering during lockdown, and thus breaking the rules, Mr Sunak also escaped most of the censure heaped on others in relation to Partygate.

What Mr Sunak may fear now is that, sooner or later, his decision-making will be revealed to have been rather less driven by science than was assumed at the time. He would no doubt also wish to suppress any candid remarks he may have made about those he was working with.

That is understandable but it is of no moral, legal or political consequence when set against the pursuit of the truth by Lady Hallett – a quest driven by a nation left feeling traumatised, and somewhat betrayed, after the first pandemic in a century. Nothing less than the whole truth will do.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments