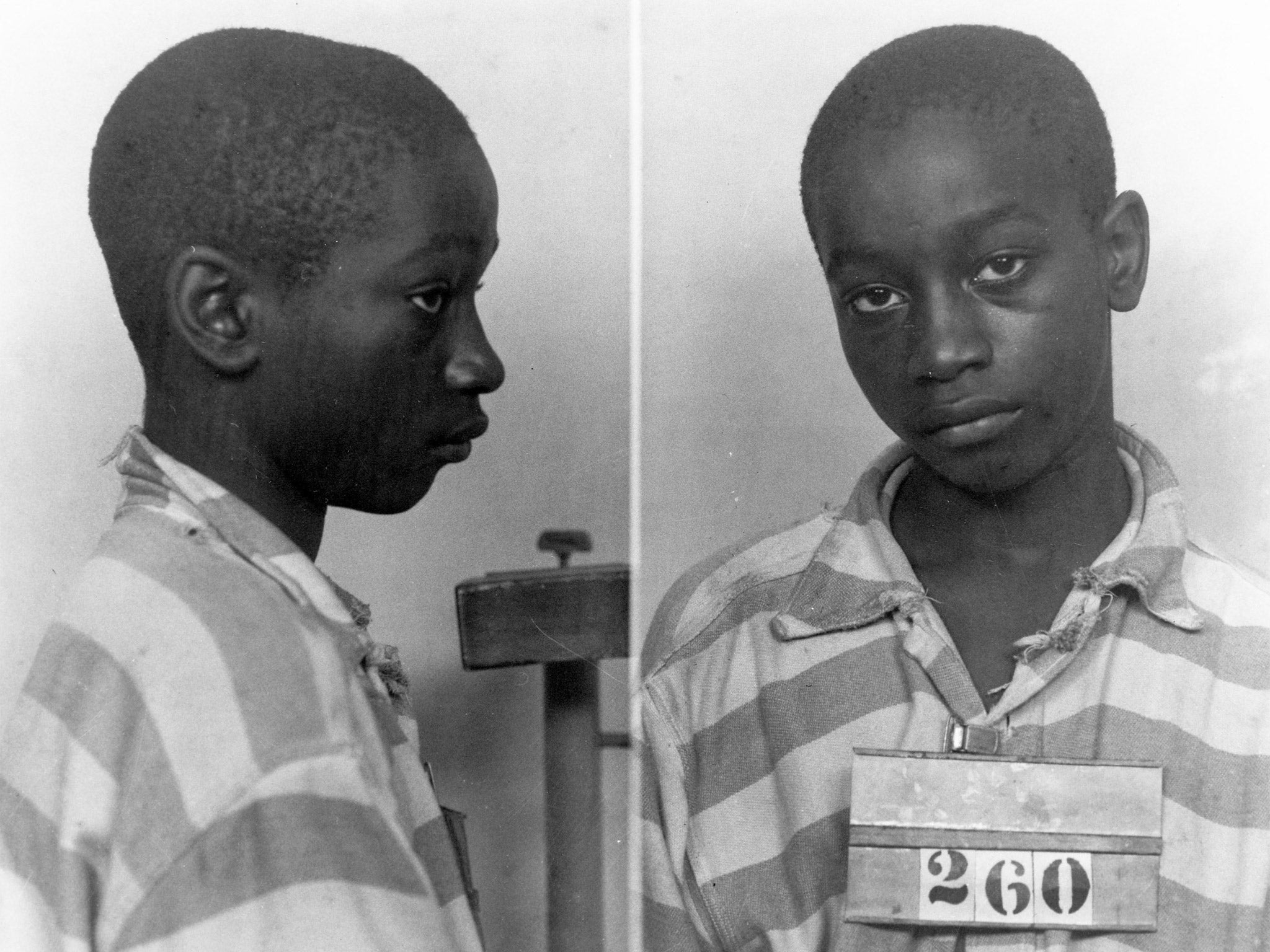

Justice for George Stinney: A 14-year-old executed in 1944 may be pardoned, but miscarriages of justice in US death penalty cases are still common today

Even when guilt is established, the suffering inflicted upon inmates goes beyond belief

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In Thursday’s Independent, Tim Walker told the story of George Stinney, a boy who was sent to the electric chair in South Carolina in 1944 for two crimes which the evidence strongly suggests he did not commit. 70 years on, Stinney – who was 14 years old when he was executed – has been granted a two day retrial.

Miscarriages of justice in the US capital punishment system have not been ironed out with the passage of time. When I worked with defence lawyers in Texas, I encountered many clients who undeservedly faced George Stinney’s tragic fate.

Take the case of Jess, who has been awaiting trial and a possible death sentence in a Harris County jail, Texas, for two years. At the age of 16, Jess, in fear and panic, stabbed a man to death who had abducted her in his car and was attempting to rape her. Jess was a nervous and kind girl who had suffered severe abuse as a child. No one who spent five minutes talking to her doubted that she acted in self-defence and had never intended to kill the man. Nonetheless, Jess faces a charge of capital murder and possible execution. As a young black girl from a poor background, her chances of acquittal by what may well be a predominantly white and male jury are uncertain at best. During her years in jail, she has been unable to see her baby daughter, who was only a few months old when Jess was arrested. Her pitiable refrain during my interviews with her was “I’m scared”.

Equally tragic was the case of Ken. Ken was an immigrant from Korea who came to Texas speaking no English. He was accused of being part of an execution-style killing of six monks, a nun and two young students in a Buddhist temple. The circumstances of the crime were obscure; the police were required to look for suspects in an insular and reticent Korean community, many of whom spoke no English, and as a result performed a patchy investigation.

Ken had a clear alibi but was unable to find the witnesses to corroborate it until after his trial. He was sent to death row in March 1992. At his stage in the appeal process, he cannot adduce evidence of innocence but can only challenge his sentence: the court will therefore not hear the witnesses who confirm his alibi. The phrase that he brokenly repeated during my interviews with him was “I’m innocent”.

Ken’s probable innocence is the most shocking of a series of injustices in his case. Ken suffers from paranoid schizophrenia and has almost no understanding of the criminal justice system through which he is being unwittingly forced. The State prosecutors have ignored his mental condition or challenged it by way of unsound medical evidence. It is entirely inappropriate that someone with so severe an illness as Ken’s should find himself on death row. Even if Ken were guilty, he would require not punishment but care.

Even where guilt is established, a term in the Polunsky Unit, Texas’ death row, inflicts upon the convicted sufferings, which, for the most part, seem out of proportion with the crime. The inmates are kept isolated and are allowed no physical contact with each other. The only time they feel another human being’s touch is when they are shackled by prison guards or, at the end, forced on to the gurney and strapped down before receiving the lethal injection.

Some receive no visits at all. Those fortunate enough to have caring families often see the support ebb away as the years on death row slip past and their appeals fail. Periodically, the friends that inmates make within death row make the 43-mile trip to the infamous Walls Unit in Huntsville, which houses Texas’ execution chamber, and do not return. Suicides are common and sometimes drawn out as inmates allow their health to deteriorate and then refuse medical attention. All the while, the clock ticks and hope fades.

That miscarriages of justice of the kind suffered by George Stinney still occur is shocking. But even where the capital punishment system works without apparent error, the victims of it are no less pitiable. Bad laws, political pressures, and inherent prejudice all conspire to overwhelm fairness. In the US, injustice is as alive today as it was in South Carolina in 1944.

__________________________________________________

Legal proceedings in Jess and Ken’s cases are on-going and the names used are therefore aliases.

__________________________________________________

Tom Coates is a pupil barrister specialising in public law, human rights, and commercial law. He spent three months working with capital defence attorneys in Houston, Texas, through the charity Amicus.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments