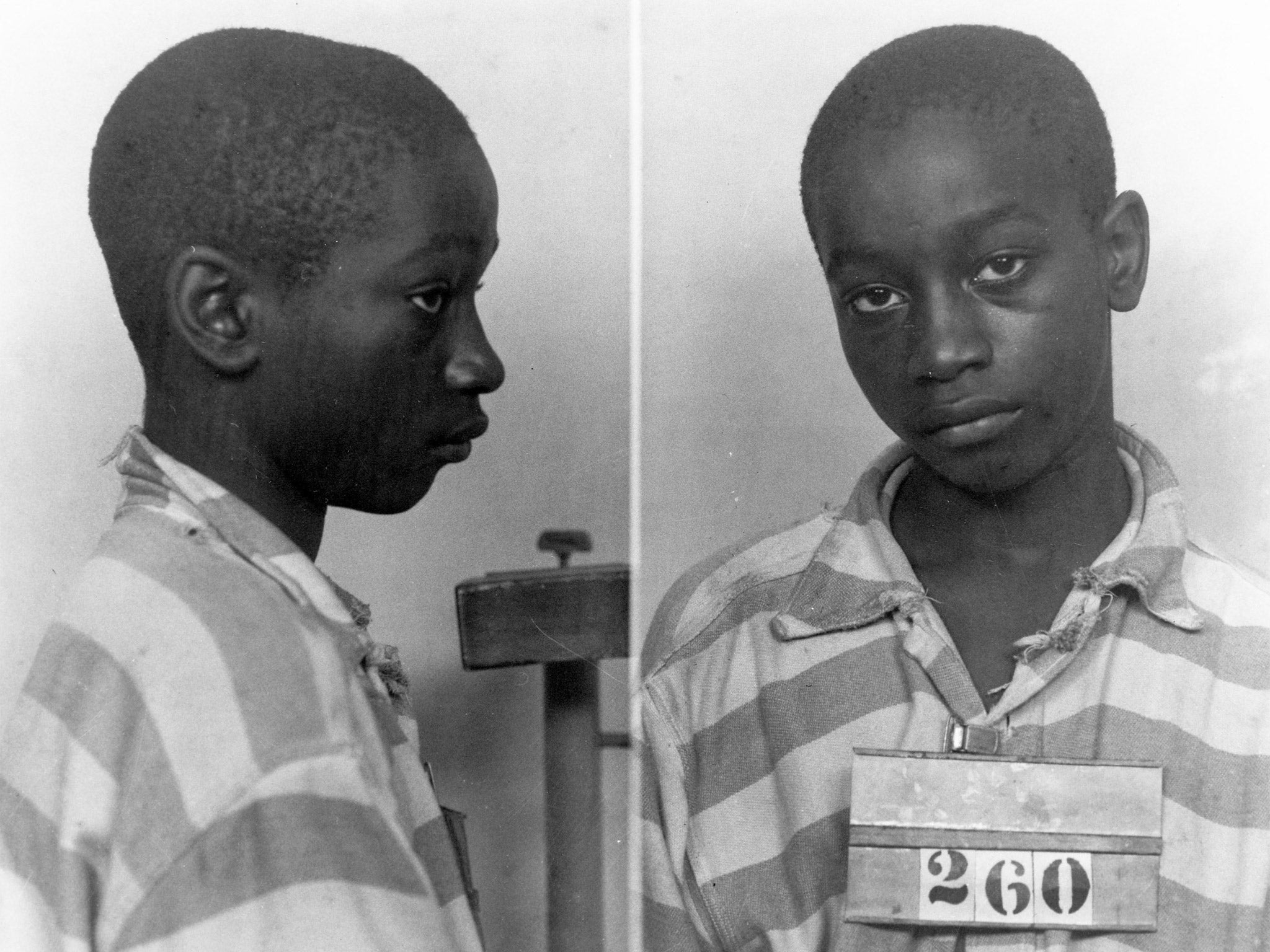

George Stinney: After 70 years, justice in sight for boy America sent to electric chair

George Stinney was 14 when executed for a crime his family says he didn’t commit. A retrial may clear his name

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.George Stinney was only 14 when a court in South Carolina sentenced him to death in 1944. The youngest person to be executed in the US since the 19th century, the black teenager was a little over five feet tall, weighed 95lbs, and had to put a bible on the seat beneath him so that he could fit into the electric chair. His feet dangled some way above the floor.

Now, 70 years on, Stinney’s family still insists he was innocent of the double murder of which he was convicted, and has asked a local judge to order a retrial and clear his name.

They and their supporters claim new evidence about the crime – and about the inadequate legal process that followed – suggest Stinney was the victim of a historic miscarriage of justice.

On 23 March 1944, two white girls – Betty Binnicker, 11, and Mary Thames, 7 – went out on their bicycles to look for wild flowers near Alcolu, a small mill town in segregated South Carolina.

Stinney’s sister, Amie Ruffner, says she and George were grazing their family’s cow close to the railway tracks that divided the town when the girls passed by.

Ms Ruffner, who is now 77, recently told WLTX, a local news station: “They said, ‘Could you tell us where we could find some maypops?’ We said, ‘No,’ and they went on about their business.”

They were the last people to see Binnicker and Thames alive. The girls’ bodies were found the following day in a nearby drainage ditch; both had suffered crushing blows to their skulls.

According to the 1944 medical examiner’s report, the injuries were probably caused by a “blunt instrument with a small round head about the size of a hammer”.

The report noted that both girls’ hymens were intact but that there was minor swelling and a “slight bruise” on Binnicker’s genitalia.

Police soon took George and his brother Johnnie in for questioning, though they later released Johnnie. “They took my brothers away and I never saw my mother laugh again,” said Ms Ruffner, who believes the authorities simply wanted a scapegoat for the murders.

Stinney was interrogated without his parents or a lawyer present. Police claimed he quickly confessed to the crime and that he had been motivated by a desire to have sex with Binnicker.

The 14-year-old’s trial lasted less than three hours, during which time his defence lawyer presented not a shred of evidence, nor any witness testimony to help his case. The all-white jury arrived at its guilty verdict after only 10 minutes. He was swiftly sentenced to death.

Afterwards, a mob of white men arrived at the local jail to lynch Stinney, but he had already been transferred to the Columbia penitentiary some 50 miles away, where, a mere 84 days after the murders, he was escorted to the electric chair.

Witnesses said that as the switch was flipped, sending a 2,400-volt surge of electricity through Stinney’s body, his convulsions caused the oversized mask covering his face to fall away, revealing his terrified features.

Stinney’s father had been among those who searched for Binnicker and Thames after they went missing, yet he was fired from his job at the local lumber mill and the family driven from the town.

Now, his three surviving children say their brother’s confession was coerced, and that George was with the family at the time of the murders.

“South Carolina still recognises George Stinney as a murderer. We felt that something needed to be done about that,” Matt Burgess, a lawyer acting for the Stinney family, told CNN.

“We think we have the opportunity here to make a difference and correct a wrong that’s been there for 70 years.”

Among the evidence in Stinney’s favour is a statement made by his cell mate, Wilford Hunter, who said the teenager had repeatedly denied committing the murders.

The defence team has also uncovered numerous violations of due process during the original case. For instance, one member of the search party sent out for the girls, whose family owned the land on which the bodies were found, was later appointed foreman of the jury at the coroner’s inquest.

A hearing to determine the future of the case began on Tuesday at the Sumter County Judicial Centre in South Carolina.

Judge Carmen Mullen told those assembled that the hearing would not produce a new verdict as to Stinney’s guilt or innocence, but simply decide whether or not he received a fair trial.

Arguing against the prospect of a retrial, Third Circuit Solicitor Chip Finney said: “The fact of the matter is, it happened, and it occurred because of a legal system of justice that was in place and that we – for all we know, based on the record – [know] worked properly.”

Many remain convinced of Stinney’s guilt, including James Gamble, whose father was the Clarendon County sheriff at the time of the killings. Mr Gamble rode in his father’s car with Stinney after the teenager was convicted, and in 2003 claimed: “He was real talkative about it. He said, ‘I’m real sorry. I didn’t want to kill them girls.’”

Two of Binnicker’s nieces also expressed their concerns about airing the old case again. Frankie Bailey Dyches said she believed Stinney had “got what he deserved” and that “justice was served, according to the laws in 1944”.

Carolyn Geddings said she felt bad for the Stinney family, but thought a retrial would only open old wounds.

“They can’t help what happened and I don’t know that they were treated fair back then,” she said.

“Once the trial is over, it will be over whatever way it goes and it’s not going to bring him back and it’s not going to bring my aunt and the other little girl back and it’s a sad situation. That’s what happened in 1944 and 70 years is a long time to keep rehashing it, it needs to be over.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments