‘I don’t think white folks as a whole have come very far’: Washington burned in the 60s, but with the new protests, there is hope

For residents who saw Washington DC burn decades ago in the wake of the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr, the George Floyd protests feel like hope, writes Rachel Chason and Rebecca Tan

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.More than five decades had passed since Poopoo Earls protested.

Back then, Earls ran through the DC streets with hordes of other young people hurt and outraged by the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. Four days of rioting left 13 dead and some of Washington’s predominantly black neighbourhoods in ruins for 30 years.

For people like Earls, who watched their communities reduced to rubble in 1968, the mass protests that erupted in the nation’s capital this month were at first a painful reminder of that chaotic point in history. The killing of George Floyd in the custody of Minneapolis police showed that the injustices of their youth had persisted. Demonstrations descending into looting and fires suggested that history was on the verge of repeating itself.

As the days wore on, however, there were glimpses that, this time, things might be different.

A 75-year-old who marched to 14th Street NW with his classmates from Howard University in 1968 was astonished by the white faces he saw this month chanting against police brutality. A woman haunted by memories of the riots 52 years ago relaxed as she wove through the peaceful crowds with her grandsons. The 86-year-old founder of Ben’s Chili Bowl, who packed food for several hundred protesters on a Saturday in June, says she couldn’t have felt prouder of her city.

Earls, 64, stayed home in the Truxton Circle neighbourhood when the Floyd protests started, worried about the risk of exposure to the coronavirus. But when she heard that one of the marches would feature the District of Columbia’s iconic go-go music, she could not resist.

She hopped onto her motorcycle and headed for 14th and U Streets NW, epicentre of the 1968 devastation. What she saw astounded her: hundreds of people – black, white, Latino and Asian – bobbing their heads and snapping their fingers to the music she had grown up dancing to.

“We ain’t never seen nothing like that,” Earls says. “We ain’t never had that many Caucasians, all walks of life, walk with us... ‘68 wasn’t like that.”

In searing 90-degree heat, Earls followed the go-go truck towards the White House, where thousands of others were wielding signs, playing drums and sharing food.

“I thank God I lived to see it,” Earls says. “It gave me hope.”

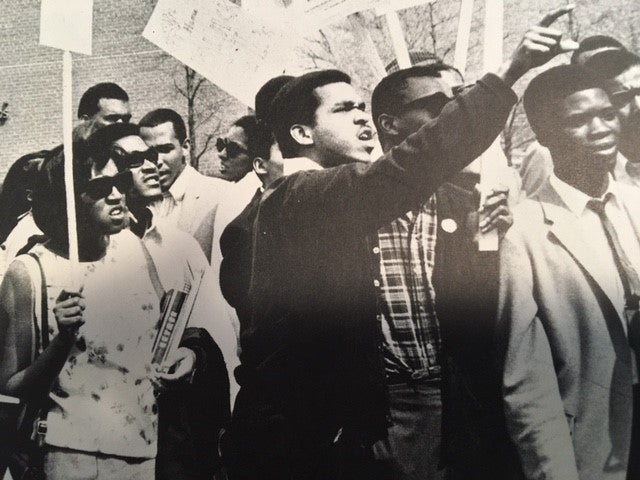

The first thing Tony Gittens remembers is the smoke. In 1968, the pungent smell of stores and homes burning followed him and his friends as they walked about seven blocks from Howard University, on Georgia Avenue NW, to 14th Street. Gittens says his eyes watered from tear gas that police had fired to clear rioters; one of his friends was quickly arrested, while another was pinned to the ground.

That April, police arrested 7,600 people on riot-related charges in the District. Seven hundred homes were destroyed, many in Shaw and along the 14th Street and U Street corridors, which had been predominantly black enclaves. Businesses were boarded up, and many families moved to the suburbs, shrinking the city’s population from 764,000 in 1960 to 638,000 in 1980. As drugs and crime took over many neighbourhoods, tens of thousands more would leave.

Jarvis says that in the 1960s, there was little understanding in the white community about the discrimination felt daily by black residents

Those who remained say it felt like the black community had absorbed the pain of King’s killing largely on its own. The riots ravaged black neighbourhoods, and when it was all over, black communities were left to pick up the pieces. While white people played a significant role in the national civil rights movement and events like the 1963 March on Washington, the protests in the District after King’s murder were deeply segregated, as was the city itself.

“We wanted to see everybody stand up for equal rights, but back in those days, it was a different time,” says Virginia Ali, who with husband Ben Ali, now deceased, founded Ben’s Chili Bowl, which served as a hub for civil rights activists in the 1960s.

“We tore up our own stuff – and we were already suffering,” says Earls, who for many years struggled with addiction and was in and out of prison for drug dealing. “We lived to regret it.”

Former DC Council member Charlene Drew Jarvis was a young mother teaching at Howard University the night King was killed. She remembers seeing the looting on 14th Street, and growing scared as she rushed to pick up her children at day care, only to find that a teacher had taken them home.

Jarvis says that in the 1960s, there was little understanding in the white community about the discrimination felt daily by black residents. Now 78, she did not join the Floyd protests because of concerns about the coronavirus. But she has had conversations about racism this month via Zoom with various civic and business groups that include both white and black residents.

“There was no marriage between protests at that time,” Jarvis says of the tumultuous days following King’s death. “This now is very different.”

Gittens, now 75, spent the last few months quarantining with his wife at their home in Washington’s Adams Morgan neighbourhood. He knows he is at risk for covid-19, but on June 6, when thousands were slated to turn up for protests, he was drawn to participate, just as he was pulled to 14th Street all those years ago.

“People just kept coming and coming and coming,” says Gittens, who stepped down as the head of the DC Arts Commission in 2008 but still serves as director of the DC International Film Festival.

He spent hours at 16th and K streets NW, marvelling at the multiracial protest. In 1968 in Washington, he says, having even one non-black friend or colleague express support for the civil rights of African Americans felt like a win. Now, there were thousands of them in front of the White House.

At one point, a young white man passed by, holding up a sign that read: “Stop killing my friends.”

“I was so moved by that, genuinely,” Gittens says. “For me, it was like a real, honest personal example of progress.”

Among the relatively few white allies in 1968 was Susanne Jackson, then Sue Orrin, a civil rights and anti-Vietnam War activist. Heeding the advice of Stokely Carmichael that white people should organise themselves, she helped to bring together more than a hundred white doctors, lawyers and journalists in a network of activists in 1967.

These volunteers deployed across the city after King’s death, providing medical assistance and legal aid and raising money to pay bond for those who were arrested. There was a curfew in place, Jackson says, but police rarely stopped or questioned white residents.

At 76, Jackson says she is heartened to see more white people protesting now than before. She lives in Memphis and stayed at home because of the coronavirus, but worked remotely to help organise protests.

He had been at 14th and U streets the evening King was assassinated, and watched as a man hurled a trash can into the window of the Peoples Drugstore

“I am very excited about the enthusiasm,” she says. “But I don’t think white folks as a whole have come very far.”

Nicole Baker was four years old when her parents returned to their townhouse in the Kenilworth neighbourhood of Northeast Washington and announced that King was dead.

For the next week, Baker and her six siblings were not allowed to go outside. Through their window, they watched people running by, sometimes carrying boxes of shoes or a TV set. When it got dark, people screamed and cried.

Decades later, her grandson Jeremy Gray declared that it was his 18th-birthday wish to attend the DC protests with his family. Baker’s first reaction was dread.

“Inside me was a fear to be in the midst of it again,” says Baker, now 55 and living in Pennsylvania.

For days, she thought about the painful times in her life when she had encountered law enforcement,including in 2018, when she watched police Taser and restrain one of her sons in Chambersburg, Pennsylvania. Gray and his two younger brothers are biracial, with lighter complexions. But Baker knew this would not stop police from seeing them as black.

Late on the evening of June 6, the grandmother and her grandsons made their way to the centre of the crowd at 16th and I streets NW. At 10 pm, when protesters raised their fists in a black-power salute, they did, too. Baker turned to look at Gray, her white Afro matching his brown one, and smiled.

“It was an honour to be part of that,” Baker says a week later. “For both of us.”

Stanley Mayes, 70, worried not just about what might happen at the protests, but what lasting damage they might leave. He had been at 14th and U streets the evening King was assassinated, and watched as a man hurled a trash can into the window of the Peoples Drugstore. For years afterward, he avoided walking to stores in the neighbourhood, concerned about his safety.

The process of revitalising the city – which Mayes helped lead as a local activist – took decades. And yet, even as the city changed, much stayed the same, he says, including black men being mistreated by police. That is why he chose to attend a protest earlier this month, he says, braving the possible coronavirus exposure.

“African Americans, period, and African American men, in particular, know this stuff,” Mayes says, sitting in the leather repair shop he owns in the Shaw neighbourhood. “We live it every day.”

Police misconduct is “a consistent theme” across the major bouts of civil unrest in the District, says historian J Samuel Walker, including in 1991, when three days of rioting erupted in the District’s Mount Pleasant neighbourhood after a 30-year-old Salvadoran immigrant was shot by an African American police officer.

“Education, poverty – it all builds on one another,” Walker says. “But often, what seems to set off a spark is police actions.”

Mayes, a lawyer, can tick off the number of times he has been stopped without cause by police, including once when he was leaving the hospital after visiting a dying client and an officer asked if he had been drinking. But he says it was not until the advent of the cellphone, and the videos of police brutality and shootings, that people started paying attention to a reality that African Americans had long been experiencing.

“For so many years, it felt like we were like Chicken Little, shouting, ‘the sky is falling!’” he says. “Finally, finally, people seemed to be listening.”

Gittens pointed out that even during this month’s protests, law enforcement officers across the country were repeatedly caught on camera exerting excessive force. After 1968, he says, he hoped never to see police swinging batons against the backs of peaceful protesters again. But he has – and knows that he is likely to again.

This doesn’t mean giving up hope, he says.

“I’m going to show up every time if that’s going to help move it forward,” Gittens says. “Every time.”

© The Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments