Martin Luther King Jr assassination: Did James Earl Ray really kill the civil rights leader in Memphis?

The petty criminal pleaded guilty to murder, but 50 years on doubts still persist that the FBI and other shadowy government forces might also have been involved in a conspiracy

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When Martin Luther King Jr checked into Room 306 of the Lorraine Motel, one of the few in Memphis to give black Americans a friendly welcome, the eyes of the world were upon him.

This was the youngest man ever to have been awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, a leader whose oratory on behalf of his people could neither be ignored nor forgotten.

That evening Dr King again showed how his words had the power to change a nation.

“Let us rise up tonight with a greater readiness,” he told a huge crowd at the Mason Temple Church. “Let us stand with a greater determination … to make America what it ought to be … to make America a better nation.”

The 39-year-old reverend spoke of narrowly surviving an attempt to stab him to death a decade previously, the blade coming so close to his heart that had he sneezed, he would have died.

In words that have now acquired a chillingly prophetic significance, he told his supporters: “I would like to live a long life … But I'm not concerned about that now … I've seen the Promised Land.

“I may not get there with you, but I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the promised land!”

No-one noticed when the following afternoon, on April 4 1968, 40-year-old James Earl Ray checked into a boarding house a block away from the Lorraine.

Why would they? Unlike Martin Luther King, this guy was a loser, a burglar, armed robber and nobody whose only talent seemed to be for getting arrested and escaping jail. That was what he had done a year earlier, slipping out of Missouri State Penitentiary by hiding in a bakery truck.

The fugitive, it would later be reported, was an admirer of Hitler, who wanted an all-white America. When he saw Martin Luther King on a prison television, his fellow convicts claimed, Ray would fly into a rage and promise: “If I ever get to the streets, I am going to kill him.”

In the shared bathroom at the back of Ray’s boarding house, there was a window overlooking the Lorraine Motel.

At 6.01pm that evening Martin Luther King was standing on the balcony of the Lorraine. A single shot was fired. The bullet hit Dr King’s right cheek, shattering his jaw and several vertebrae and severing his spinal cord.

The civil rights leader was pronounced dead at St Joseph’s Hospital at 7.05pm.

Ray’s fingerprints were found on a Remington .30-06 Gamemaster rifle dumped near the front of the boarding house.

He was arrested 65 days later, at London’s Heathrow Airport, while apparently trying to flee to what was then the white supremacist haven of Rhodesia, (now Zimbabwe).

On March 10 1969, James Earl Ray pleaded guilty to the assassination of Dr Martin Luther King.

He was sentenced to 99 years in jail. The Lorraine Motel was eventually converted into the National Civil Rights Museum.

It was an open and shut case.

Except, of course, it wasn’t. Fifty years on, controversy continues to rage about the death of Martin Luther King.

Even during the relatively brief Memphis courthouse proceedings, Ray had leapt to his feet when both the prosecutor and his own defence lawyer Percy Foreman agreed that there was no evidence that anyone else had conspired to kill Dr King.

Ray insisted that he had not intended his guilty plea to be taken as meaning that no others had been involved.

The guilty plea, of course, had allowed him to avoid the executioner’s electric chair.

Three days after pleading and being sentenced, Ray wrote to the judge saying he wanted to retract his confession.

Never again could the assassination of Martin Luther King be laid to rest and universally accepted as the work of a lone racist with a gun.

After half a century, there has been a profusion of alternative theories presenting Ray as having been directed by shadowy, powerful government forces, either as a paid assassin or as an unwitting patsy.

Some of this was almost inevitable. For such a great man to be killed by such a petty, peripheral figure as Ray seems almost to offend the natural order of things. Many conspiracy theories, it has been noted, spring from the fact that the human mind seems to need grand causes for great events.

But when it comes to the controversy around Dr King’s death, it is rather hard to instantly dismiss everything as the delusions of “conspiracy theorists”.

For one thing, Dr King’s own family have been among the most prominent in suggesting that Ray might have been framed.

In March 1997, one of Dr King's two sons, Dexter Scott King, visited Ray in prison and said he thought he was innocent.

Until the day she died in 2006, Dr King’s widow Coretta believed what she had told a press conference in December 1999: “There is abundant evidence of a major high level conspiracy … The Mafia, local, state and federal government agencies, were deeply involved in the assassination of my husband … Mr Ray was set up to take the blame.”

To the King family and many others who lived through the civil rights struggle of the Sixties, the idea of such high-level government involvement in an assassination plot was anything but fanciful.

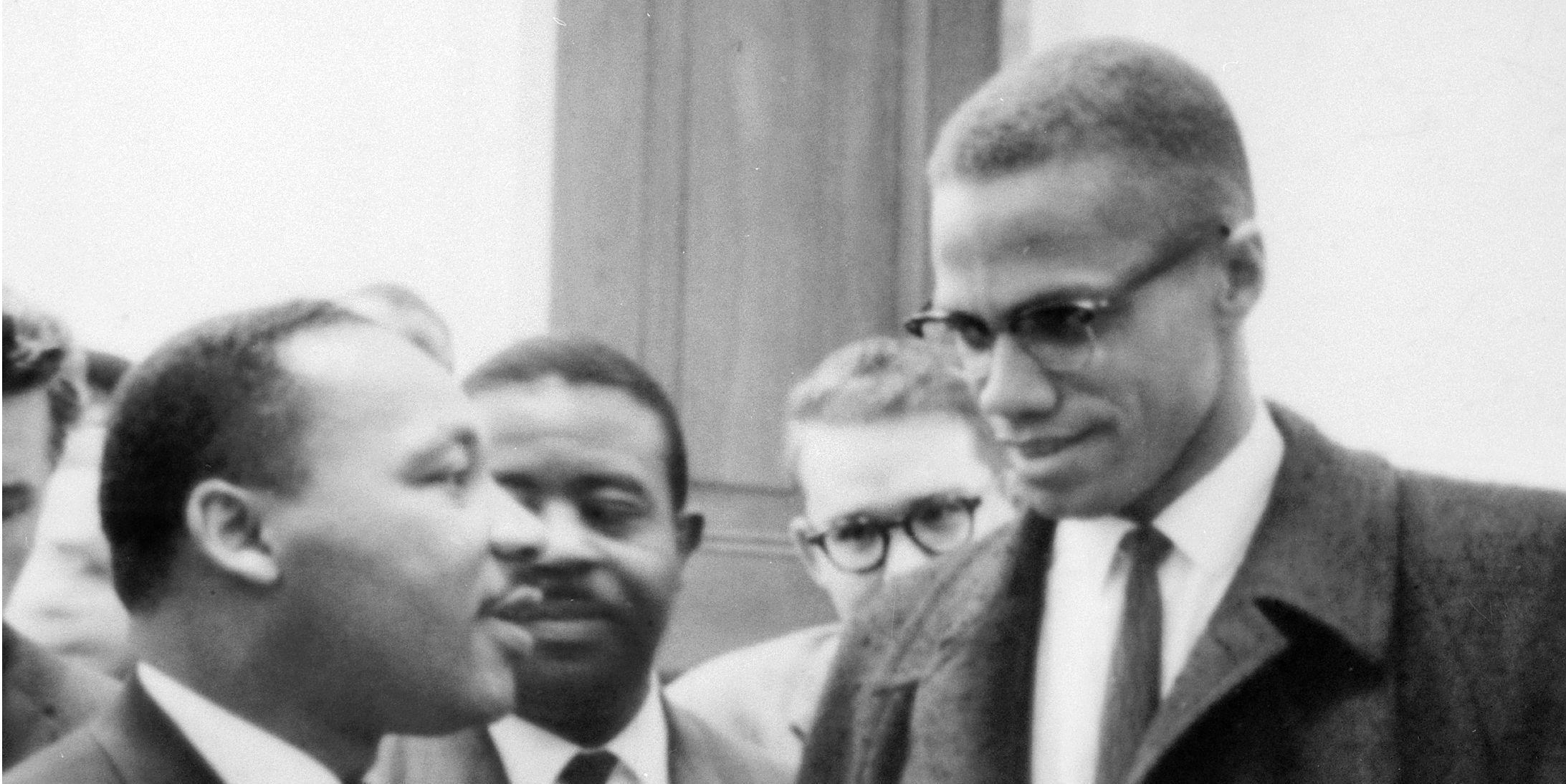

They had suffered from racial discrimination all their lives, seen police brutality at first hand at civil rights and Vietnam War protests. Moreover, this was the era of assassinations – John F. Kennedy had been killed in 1963, the black leader Malcolm X in 1965.

Dr King knew the FBI had been operating against him. On November 18 1964 none other than J. Edgar Hoover, the director of the FBI, had publicly denounced him as “the most notorious liar in the country”.

A few days later, Coretta opened a package addressed to Dr King, thinking it contained a recording of her husband’s speeches. Instead there was a letter that claimed the enclosed tape was of Dr King having sex with other women, although the recording turned out to be so unclear that Coretta dismissed it as “mumbo jumbo”.

The misspelt letter accused Dr King of being a “colossal, evil, vicious fraud”, and denounced him as an “abnormal beast”.

In what many interpreted as a hint that he should kill himself, the letter stated: “There is only one thing left for you to do”.

Dr King and everyone around him immediately concluded that what became known as “the suicide letter” was the work of an FBI agent.

We now know that the FBI had been wiretapping Dr King’s phones since 1963 and had started a counterintelligence operation to discredit him.

Hoover, who in one memo called Dr King “a tom cat with obsessive degenerate sexual urges,” was amazed and frustrated when FBI efforts to plant stories about the civil rights leader’s sex life came to nothing.

Small wonder, perhaps, that Dr King’s family could suspect the government of involvement in his murder.

In reaching such conclusions they were assisted by a perhaps unlikely ally: Ray’s new lawyer William F. Pepper.

It was Pepper who did much to publicise the story that Ray was now telling from his prison cell, in between his four attempts to escape from it.

Ray insisted that the real story was that after escaping from the Missouri State Pen, he had been approached by a blond Cuban going by the name of Raoul.

The mysterious Raoul had got him to buy the rifle and to book a room at the boarding house, Ray claimed.

The convicted man’s story was that Raoul had taken the gun and then the Cuban, or an accomplice, had shot Dr King before dumping the rifle where it would be found with Ray’s prints on it.

In 1993, there was another twist. Loyd Jowers, who had owned Jim’s Grill, the café on the ground floor of the boarding house building, gave a televised confession that he had been paid $100,000 by a Memphis businessman with links to organised crime to arrange the murder of Dr King.

Jowers claimed the real gunman was a rogue Memphis Police Department lieutenant acting on his instructions. This was possible because the fatal bullet had not necessarily come from the Remington rifle. Ballistics tests had failed to prove or disprove its use in the assassination of Dr King.

Adding to the intrigue was Pepper’s stated belief that green beret snipers from a top secret unit known as Alpha 184 had been after Dr King. They had actually had him in their rifle sights, it was claimed, but before they could pull the trigger, another, unknown gunman had fired the fatal bullet.

It all came to a head in 1999, when the King family brought a wrongful death lawsuit against the now ailing and elderly Mr Jowers. They were represented by Mr Pepper.

In December 1999, after four weeks of testimony involving more than 70 witnesses and thousands of pages of evidence, a Memphis jury unanimously found that Jowers had conspired in the assassination of Dr King with “others, including government agencies”.

At the post-verdict press conference, Coretta King issued her statement about “abundant evidence of a major high level conspiracy.”

Others, though, begged to differ.

In his 1998 book Killing the Dream: James Earl Ray and the Assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr the author Gerald Posner claimed Jowers – who died in 2000 – had been spinning a yarn for money.

He quoted a telephone conversation, which he said had been recorded by the authorities, which suggested that Jowers had been hoping to get a $300,000 film deal.

Posner claimed that military order papers cited by Pepper as proof of the existence of sniper unit Alpha 184 had been forgeries. Posner also revealed that a soldier said by Pepper to have been killed as part of the subsequent government cover-up was alive – and suing Pepper for libel.

Posner concluded that Ray really was a lone assassin, and also suggested he might have got away with it had he not panicked and dumped his rifle when he saw two police cars parked near the boarding house.

As for Raoul, Posner claimed to have tracked down the man Pepper suspected of being the mysterious Cuban, only to find he was from Portugal and the records of the auto company which employed him showed he had been working in New York on April 4 1968.

In claiming that Raoul was a figment of Ray’s imagination, Posner was following the line taken by what some regard as the most thorough government investigation into the assassination of Dr King.

In 1979 the US House Committee on Assassinations reported that Raoul did not exist.

It acknowledged the existence of a counter-intelligence operation against the civil rights leader, but still concluded: “No federal, state or local government agency was involved in the assassination of Dr King.”

That, though, did not mean the committee accepted the first court verdict that Ray had acted entirely on his own initiative.

Far from it.

“After examining Ray's behaviour, his character and his racial attitudes,” the report stated, “The committee found it could not concur with any of the accepted explanations for Ray as a lone assassin.

“The committee concluded that there was a likelihood of conspiracy in the assassination of Dr King.”

In its report the committee outlined a strong suspicion that Ray had killed for money, as part of a broader plot – not a government conspiracy, but a conspiracy nonetheless.

The committee raised the possibility of a conspiracy involving Ray’s two brothers John and Jerry, despite both men’s denials.

The committee claimed James Earl Ray had committed a bank robbery after his escape from prison, which might have helped explain how he had the money to go on the run and cross the Atlantic to England after the assassination.

And, most intriguingly of all, the committee uncovered “substantial evidence” of a secret bounty on Dr King’s head that was being offered by a covert Southern organisation centred around St. Louis patent lawyer John Sutherland and his associate John Kauffman.

It heard St Louis criminal Russell George Byers testify that in late 1967 or early 1968 he had declined Sutherland’s offer of $50,000 to kill Dr King.

In 1968, the committee found, Sutherland and Kauffman had both been campaigning in St Louis, helping to stir up “intense support” for the US presidential bid of George C. Wallace who was running on the ticket of the American Independent Party (AIP).

So, the committee said, John Ray could have heard about their secret bounty while running his St Louis bar the Grapevine Tavern.

The committee suggested that James Earl Ray could then have acted in the general expectation of receiving the secret bounty, or “after reaching a specific agreement, either directly or through one or both brothers, with Kauffmann or Sutherland”.

There were caveats of course:

“The committee frankly acknowledged that it was unable to uncover a direct link between the principals of the St. Louis conspiracy and James Earl Ray or his brothers.

“There was no direct evidence that the Sutherland offer was accepted by Ray, or a representative, prior to the assassination.

“In addition, despite an intensive effort, no evidence was found of a payoff to Ray or a representative either before or after the assassination.”

The committee regretted that the evidence it had uncovered had not been pursued in 1968:

“It is a matter on which reasonable people may legitimately differ, but the committee believed that the conspiracy that eventuated in Dr. King's death in 1968 could have been brought to justice in 1968.”

But this government account was ultimately not accepted by the King family.

Even before the civil lawsuit of 1999 produced a very different conclusion, the family had been asking President Bill Clinton to look again at the assassination.

As a result, special counsel Barry Kowalski took yet another look at the murder.

But in 2000, Kowalski who had previously been the prosecutor in proceedings against the Los Angeles police officers accused of beating Rodney King, sided with those who believed the government had nothing to do with the assassination.

“Our thorough investigation,” Kowalski said earlier this week, “Just like four official investigations before it, found no credible or reliable evidence that Dr King was killed by conspirators who framed James Earl Ray. I remain absolutely convinced this well-supported finding is correct.”

James Earl Ray died in prison, of natural causes, in 1998.

After the death was announced, John Campbell, the Memphis assistant district attorney who had investigated – and dismissed – some of the conspiracy claims, insisted: ''He killed one of the greatest men of this century by his own admission. He spent his life in prison, and justice has been served.''

But Dr King’s widow Coretta issued a statement of her own.

The death of the man jailed for murdering her husband, she said, was “a tragedy for the entire nation.”

Mr Ray had never had a trial, she said. America had never learned the truth.

Fifty years after a single bullet was fired in Memphis, one is left with a troubling conclusion: the legacy of Dr Martin Luther King will endure, but so too will the doubts about his death.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments