The human cost of Doritos: Claims of 84-hour work weeks and stagnant wages at Frito-Lay factory where workers are on strike

Employees at the snack giant’s facility in Kansas demand an end to unpredictable hours and what they call hazardous conditions amid soaring profits, reports Alex Woodward

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

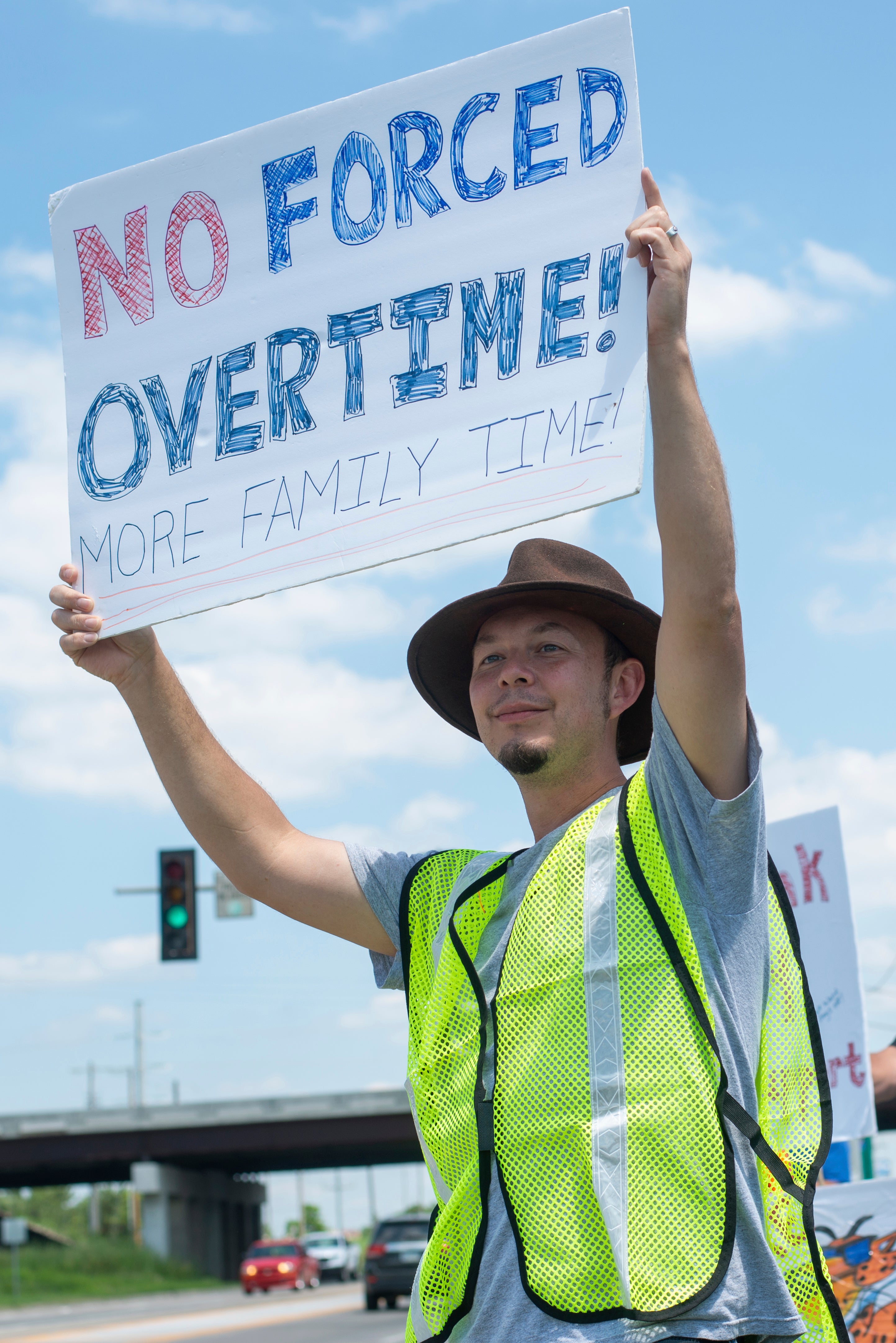

Your support makes all the difference.As of midnight on 5 July, hundreds of employees at one of the nation’s largest snack manufacturers went on strike, demanding better workplace protections and an end to forced overtime that has pushed Frito-Lay workers in Topeka, Kansas to the brink.

For nearly two weeks, roughly 600 workers at the Frito-Lay plant have been on strike, calling for better pay, stronger workplace protections and an end to unpredictable overtime schedules and staff shortages that workers say have endangered their lives on the job and stretched them too thin despite years of warnings.

Workers have reported what they say are stagnant wages that have not kept pace with the cost of living and no meaningful raises in more than a decade despite the company reaping billions of dollars in profits during the coronavirus pandemic.

Their claims of hazardous working conditions have allegedly been met with indifference, according to workers.

When a worker died on the line, “you had us move the body and put in another co-worker to keep the line going”, said Cherie Renfro, a Frito-Lay worker writing to the company in The Topeka-Capital Journal.

On 27 June, the Local 218 chapter of the Bakery, Confectionery, Tobacco Workers and Grain Millers Union notified local labour leaders that its membership authorised a strike by a vote of 353-30.

Frito-Lay said it was “shocked” by the vote.

“We believe a strike would be the most harmful outcome for everyone involved, especially our employees,” the company said in a statement.

Ms Renfro told the company she is “shocked you are so out of touch with your employees you didn’t see this coming”.

“This storm has been brewing for years,” she said.

Frito-Lay – the ubiquitous industry giant and subsidiary of Pepsi Co, with more than two dozen brands under its umbrella, including Lay’s chips, Cheetos and Doritos – operates more than 30 facilities in the US.

In her letter to the company, Ms Renfro accused the company of dismissing workers’ concerns about inhaling smoke and fumes after a fire at the facility. She also said she did not receive any hazard pay while management worked remotely during the pandemic, and reported that a co-worker was denied bereavement leave when their father died in another state.

Workers struggled to keep warm through a deep freeze, she claimed, and inexperienced temporary workers have been involved in “numerous” accidents.

“You have pushed us into a corner and we came out swinging,” Ms Renfo told the company.

The Topeka facility has been fined in several recent cases involving an employee’s amputation, according to reports filed with the Occupational Safety and Health Administration. The agency also is investigating an incident from May involving a forklift.

The plant has remained operational through the strike, and the company is hiring temporary workers – it plans to host a career fair later this month to recruit more workers.

“We continue to welcome any employees who are part of the bargaining unit on strike to continue to work as they are legally entitled to do,” a company spokesperson told The Topeka-Capital Journal. “We are currently not permanently replacing employees who are on strike.”

Anthony Shelton, international president of the Bakery, Confectionery, Tobacco Workers and Grain Millers Union, said the strike “is about more than wages and benefits. It is about the quality of life for these workers and their families.”

“This strike is about working people having a voice in their futures and taking a stand for their families,” he said.

The union has “repeatedly” asked the company to hire more workers to meet the pace of their demands against the current staffing levels, “and yet despite record profits, Frito-Lay management has refused this request”, Mr Shelton has claimed

Workers are “left with no choice but to strike to defend the livelihoods of themselves and their families,” he said. “We simply ask that management recognize the sacrifices our members have made, and work with us to find a solution that promotes the well-being of our membership and their families.”

Earlier this week, Pepsi reported that its quarterly revenue rose by more than 20 per cent from 2020, with recent stock increases giving the company a market value of more than $211bn.

Its growth is also fuelled by sales from Frito-Lay, which recorded more than $4bn in sales in 2020 as Americans hunkered down during the pandemic.

Mark Benaka, Local 218’s business manager, has called on labour leaders to “discourage the purchase of any Frito-Lay, Pepsi, Gatorade, Starbucks, Lipton, Tropicana and Stacy’s products” under the Frito-Lay and Pepsi umbrella “until a resolution or agreement in place to protect our members and their family’s financial livelihoods”.

The company’s two-year agreement with the union expired in September 2020 and was extended through the end of June, but the union voted against a new contract with a two per cent wage increase and 60-hour work week cap. Members rejected the wage increase as insufficient, and the overtime cap would mean more senior workers would be forced to work weekends, according to workers.

“We want to go home and see our families. We want to have our weekends off. We want to work the time that we agreed to work – and hopefully not much more than that,” factory worker Monk Drapeaux-Stewart told Labor Notes.

Mr Drapeaux-Stewart said his wages have increased by only 77 cents within the last 12 years.

“Fifteen, 20 years ago Frito-Lay had a really good reputation – all you need is a high school diploma and you’ve got this job with good pay and benefits,” he said. “But slowly all of that has been whittled away.”

On 19 July, the union’s contract negotiating committee will reconvene with the company to hash out better terms, though it is unclear whether Frito-Lay will update its last offer.

In a statement issued by the company on 14 July, Frito-Lay said it is “committed to providing a safe and fair workplace for all of our employees”.

“We believe our existing two-year offer addresses the concerns that have been raised at our Topeka facility,” the company said. “That good-faith offer, which was recommended by the entire union bargaining committee, accepted the union’s proposal for across-the-board wage increases and improved work rules that would reduce overtime and hours worked.”

The statement added that the company believes the strike “unnecessarily puts our employees at risk of economic hardship, and we are focused on resolving this matter as expeditiously and fairly as possible”.

The strike is among several high-profile organising efforts and strikes across the US amid a pandemic that has underscored a widening wealth gap in the US while the nation endures a lingering economic fallout from the public health crisis despite the growing fortunes of America’s largest employers.

Hundreds of Volvo workers are on strike in Dublin, Virginia, and a months-long strike is still underway among miners in Alabama. After a high-profile union vote among workers at an Amazon warehouse in Bessemer, Alabama, failed to join the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union, labour organisers accused the retail giant of busting a campaign to create the first-ever union in the company’s history.

A potential union at the nation’s second-largest retailer, founded by the world’s wealthiest man, marked a turning point for US labour; The International Brotherhood of Teamsters, one the largest labour unions in the US, passed a resolution committing to “supply all resources necessary” to help unionise workers at Amazon as a “top priority” for the union.

The Frito-Lay strike also comes as members of Congress revive debate over the White House-backed Protecting the Right to Organise Act, or Pro Act, which would constitute one of the largest labour provisions since the New Deal era, taking aim at so-called “right to work” laws in 27 states.

US Senator Bernie Sanders has confirmed that parts of the measure – which has broad support among Democrats, including moderate Joe Manchin – are included in proposals for a $3.5 trillion budget bill, a measure that can be passed in a marginally Democrat-controlled Senate through a reconciliation process on a simple majority vote.

Union membership has neared all-time lows across the US, while income inequality has widened, according to the Economic Policy Institute, a progressive think tank.

A report from the organisation earlier this year found that the annual median income for a full-time worker is $3,250 less than similar work in 1979 amid declining union enrolment.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments