How Amazon busted a historic union effort in Alabama

Amazon may have won the battle, but copycat union efforts and impending legislation from the Biden administration suggest the war is not yet over, write Richard Hall and Alex Woodward

For a while, at least, it was a David vs Goliath battle.

Workers at a warehouse in Bessemer, Alabama, chose to take on one of the biggest companies in the world and form a union. If they were successful, they would be the first in the company’s history. The potential for similar efforts in thousands of warehouses across the country would have risen dramatically. Amazon, America’s second-largest employer, would have been forced to contemplate an entirely new relationship with its gigantic workforce.

When the results were in, however, the analogy broke down. Goliath had won. By Friday morning, the “no” vote on the question of whether to form a union had secured a majority.

But even before the results were in, those involved in the organising effort accused Amazon of deploying an array of union busting and dirty tactics in its campaign. Among the accusations were that it improperly pushed the US Postal Service to install a voting mailbox at the Bessemer warehouse, that it forced employees to attend mandatory meetings in which they were pressured to vote “no”, and that it launched a coordinated and anti-union misinformation campaign.

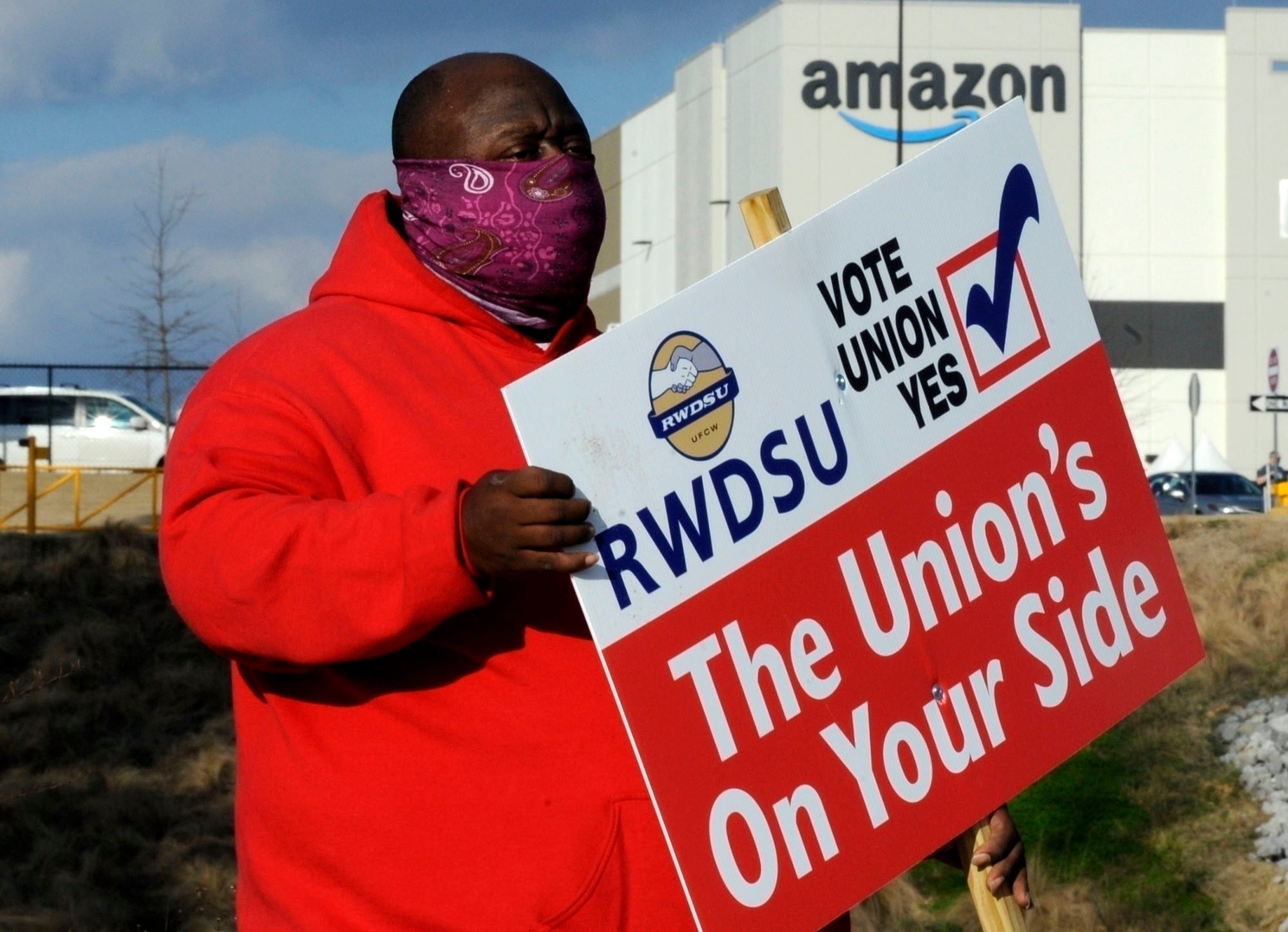

In the aftermath of the vote, the Retail Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU), which led the effort, promised a legal challenge against what it claimed was “egregious and blatantly illegal actions” by Amazon.

“Amazon has left no stone unturned in its efforts to gaslight its own employees,” said Stuart Appelbaum, president of the RWDSU, in a statement. “That’s why they required all their employees to attend lecture after lecture, filled with mistruths and lies, where workers had to listen to the company demand they oppose the union. That’s why they flooded the internet, the airwaves and social media with ads spreading misinformation.”

Mr Appelbaum further accused the union of bringing in “dozens of outsiders and union-busters to walk the floor of the warehouse” and “lying about union dues in a right to work state.”

An Amazon spokesperson said in response to the allegations: ““We respect our employees’ right to join, form, or not to join a labor union or other lawful organisation of their own selection, without fear of reprisal, intimidation, or harassment. We followed all NLRB rules and guidelines as it relates to union campaigns and we believe it is important for all employees to understand all sides of the vote and the election process itself.”

The campaign to unionise in Alabama attracted national attention from politicians and celebrities: Bernie Sanders, Danny Glover, Tina Fey and even president Joe Biden all lent their support to the effort. As voting was underway, Mr Biden released a video of encouragement for “workers in Alabama” who were seeking union recognition.

“This is vitally important, a vitally important choice as America grapples with the deadly pandemic, the economic crisis and the reckoning on race — what it reveals (about) the deep disparities that still exist in our country,” he said in the video message.

Amazon saw the vote in equally stark terms, launching an aggressive anti-union campaign to dissuade the facility’s nearly 6,000 employees from voting to organise collectively. It hired “union-avoidance consultants” from outside companies who are specialised in defeating union efforts and held mandatory meetings where its workers were forced to listen to lectures about the pitfalls of union organising.

In one of the most controversial tactics, which has been seized upon by the RWDSU and is likely to form a key part of its legal challenge, leaked emails showed that Amazon pushed the USPS to install a mailbox immediately outside of the Bessemer facility. The company then urged its employees to use the box to cast their vote, a tactic which the union said might imply that the company itself would see and count the ballots, and thus intimidate them from voting in favour.

Amazon spokesperson Maria Boschetti told The Independent: “We said from the beginning that we wanted all employees to vote and proposed many different options to try and make it easy. The RWDSU fought those at every turn and pushed for a mail-only election, which the NLRB’s own data showed would reduce turnout. This mailbox – which only the USPS had access to – was a simple, secure, and completely optional way to make it easy for employees to vote, no more and no less.”

Amazon also took the fight online. The company’s public relations chief and former press secretary for Barack Obama, Jay Carney, argued on Twitter with Bernie Sanders over working conditions.

Amazon’s decision to go full force against the union drive in Alabama followed a pattern of coming down hard on any organising efforts.

In March last year, as the coronavirus was sweeping across America, an Amazon worker at a facility in Staten Island, New York, organised a walkout over concerns about safety practices. He was promptly fired, and leaked minutes from a meeting of top-level Amazon executives that revealed how the company planned to go on a public relations offensive targeting Mr Smalls.

At a meeting of Amazon’s senior management, the company decided on a strategy to “make him the most interesting part of the story, and if possible make him the face of the entire union/organising movement,” according to minutes from the meeting which were later leaked to Vice News.

“He’s not smart, or articulate, and to the extent the press wants to focus on us versus him, we will be in a much stronger PR position than simply explaining for the umpteenth time how we’re trying to protect workers,” wrote Amazon general counsel David Zapolsky in notes from the meeting, which was attended by CEO Jeff Bezos.

Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders were among a group of lawmakers who sent a letter to the company’s CEO Jeff Bezos in October last year after reports emerged that the company infiltrated private social media groups to track employee discussion of union organising efforts.

In the end, Amazon’s strategy in Alabama won out. But even a defeat for the union organisers there could prove to be consequential in the battle over worker rights in America. President Biden, a self-described “union man,” is currently spearheading efforts to pass legislation that would make it easier for employees to start and join a union, and place restrictions on what companies could do to suppress union organising.

The White House-backed “Protecting the Right to Organise Act”, or PRO Act, is among one of the largest labour provisions since the New Deal era, taking aim at so-called “right to work” laws in 27 states.

The measure passed the Democratically controlled House of Representatives in March. Republicans in Congress have revived familiar arguments against expanded union support, saying it would crush business as employers struggle to reopen on thin margins in the wake of the pandemic’s economic fallout.

If signed into law, the PRO Act would prohibit employer retribution against workers seeking to organise and give unions greater control over voting and organising. It also would allow the NLRB to fine companies that do not comply with its orders.

It follows a decades-long campaign against organised labour in the US, once critical to the nation’s labour force and Democratic support, and undermined by growing corporate influence over politics.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments