Being told to be ‘grateful for the legacy of empire’ is akin to telling us we should accept we’re inferior

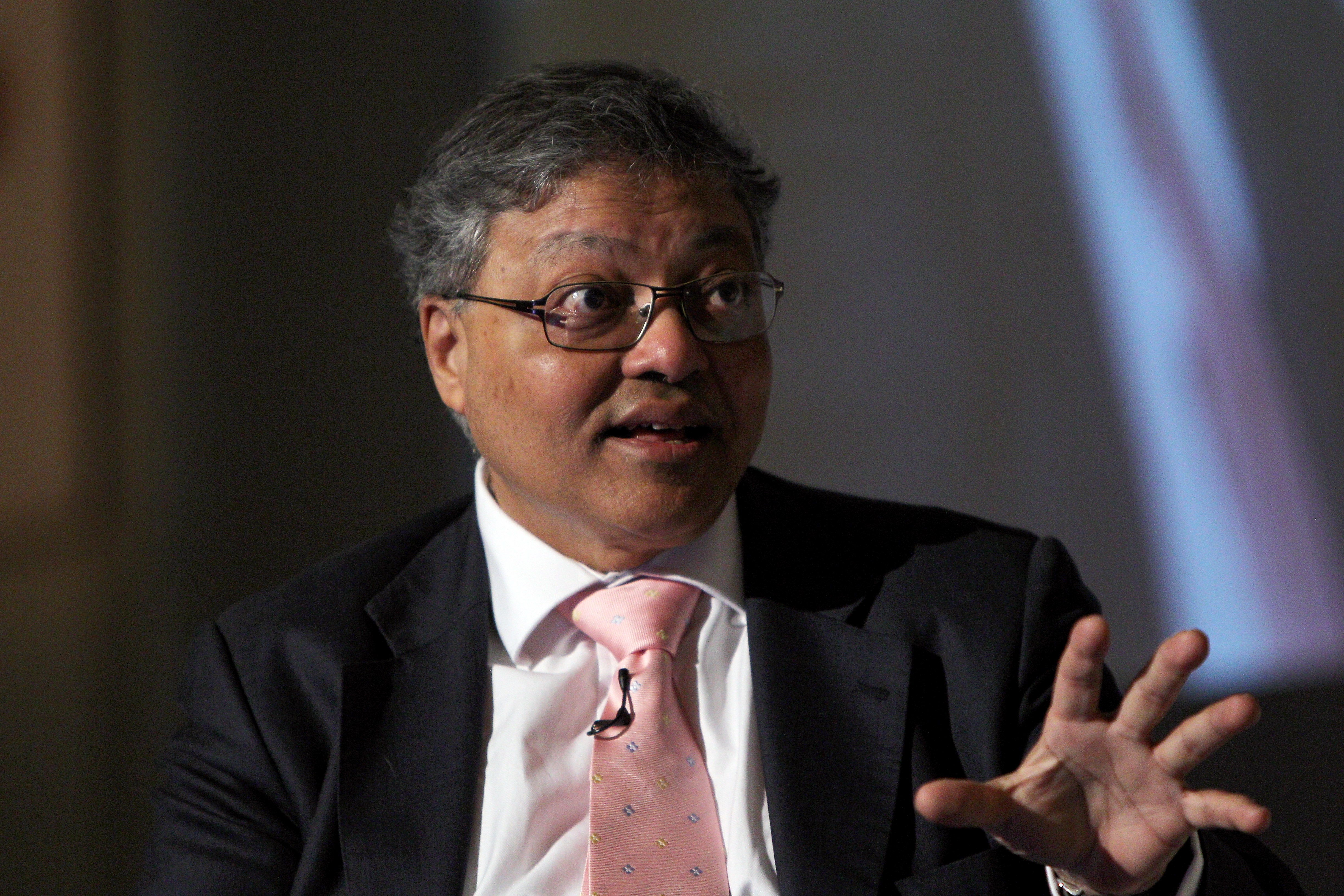

There is a lot about life in Britain to be grateful about, says broadcaster and author Mihir Bose, but when Robert Jenrick tells Indians like me that we should show gratitude for being colonised, he might as well be asking us to gather in Westminster Hall to lick his boots

Those who forget the past,” warned George Santayana, “are condemned to repeat it.” And Britain should need no lessons on how to reconcile its history; you only have to walk past the Houses of Parliament to realise that. There stands the statue of Oliver Cromwell, the man who beheaded a king and established a republic. Every year, the Cromwell Society assembles at the statue to celebrate his birthday, yet his body isn’t even there.

After the restoration, Cromwell’s body was dug up from his tomb at Westminster Abbey, his head stuck on top of Westminster Hall, and his body, after being hung at Marble Arch, was dumped in a pit somewhere beneath Hyde Park Corner. His bones lie under the road there to this day. Yet now, whenever the monarch addresses parliament, he passes this statue with no questions asked, showing how a country with no appetite for the return of the republic can still honour the founder of a republic.

In stark contrast, the country is struggling to reconcile its imperial history. This failure is all the more remarkable, as in the nearly 60 years that I have lived in Britain, I have seen it reinvent itself into a much more welcoming country.

I could not have imagined this when I arrived from India in January 1969, nine months after Enoch Powell’s Rivers of Blood speech, where he called for a policy of repatriation of “coloured” immigrants to be enforced. This was a time when people did not conceal their racism. A landlady in Hampstead told me she could not rent a room to me as her husband would not like an Indian in the house. A white woman ended our relationship because I could not provide her with white babies.

During the first summer of my university holidays, I worked in a factory in Leicester, where the foreman introduced me as “Mick”. This prompted one of his mates to say, “Bloody hell, we’ve now got a coloured Irishman, have we?” and the whole factory floor burst into raucous laughter. In 1980, while travelling on the Piccadilly line, a skinhead punched me in the face, sending my glasses flying. As I bent down to gather them, the rest of the passengers looked on as if they were in a cinema watching a film.

Yet, at the same time that I was being reminded that my skin colour made me an unwelcome outsider – a realisation that was both shocking and difficult to deal with – there were others who reassured me that the cosy image of England I had formed while growing up in India, the land of Shakespeare, Shelley, and cricket on the village greens, was not a complete fantasy. Six weeks after arriving at Loughborough to study, I was elected president of the student union at a university that then had an almost wholly white student population. I was told by one student that she had voted for me because I had a trustworthy face and would not run away with the union’s funds.

I could not have imagined then that Indian food would one day become the national cuisine. I remember landladies seeking reassurance that if they rented me a room, I would not cook Indian meals, as they could not abide the smell. Nor could I have predicted that five years after being turned down for admission to Cardiff University’s journalism course, I would fulfil my dream of becoming a journalist. Doors in the media would open to me in the UK in ways they never would have in the land of my birth. Yes, there was discrimination, with most Fleet Street sports editors, who, while prepared to believe my Indian background meant I knew about cricket, were unable to accept that I could possibly know anything about football.

The exception was John Lovesey, sports editor of The Sunday Times, whose first assignment for me was to cover Chelsea vs Tottenham – a team I had been a fan of since the age of 14. In 1981, when my life was threatened by racist fans, Lovesey devoted a whole page to my experiences, including the time an Arsenal supporter chased me down the train shouting, “C**n, c**n, hit the c**n with a baseball bat”, then a popular football song.

I have found that an Englishman or woman’s home, far from being a castle where strangers are unwelcome, can be a place where they can warmly invite in a journalist who they have never met and whose name they cannot pronounce. This has included great writers like Malcolm Muggeridge and socialites like Lady Diana Cooper, who agreed to be interviewed by me at her home overlooking London’s Little Venice. When I left she handed me a signed copy of her autobiography which I still treasure to this day. In India, a lady of that status would have been surrounded by “chammas”, courtiers, who would have denied me access unless I had come highly recommended, and the lady would never have given me a present.

Confronted by racism in the early years in the UK, I agreed with the French Afro-Caribbean philosopher Frantz Fanon that colonialism forced “the people it dominated to ask the question constantly: ‘In reality, who am I?’”. Now, I do not see being asked “but where are you really from?” as all people of colour invariably are, as racist. Britain has helped me discover my ancestral roots and be proud of them and I do not feel any shame in saying I’m of Bengali origin and a Hindu, something I would have denied in 1969, so keen was I to be accepted by the natives.

In fact, I now feel sorry for the many Britons who were born here, but who feel alienated from their roots and are afraid to even know their past. An acquaintance of my wife, when told about my memoir, immediately asked: “Does it say bad things about Britain? Then I don’t want to know.”

People like that see anything that suggests British imperial rule as anything but a moral blessing as questioning the very foundations of Western civilisation. They prefer polemical pamphlets more suited to Speakers’ Corner eulogising imperial rule rather than well-researched histories which clearly show that there was little to be proud of. Robert Jenrick, hoping to be the leader of the Conservatives, has even gone further and claimed former colonies should be grateful for the legacy of the empire.

How George Orwell would have laughed at such an assertion.

The greatest political writer of the 20th century described the empire as “in essence nothing but mechanisms for exploiting cheap coloured labour”. Orwell, having seen the empire first hand, came to this conclusion in July 1939, two months before the Second World War started.

That a man like Jenrick, who hopes to lead the country, has evidently not read this seminal essay is shameful. Reading Jenrick’s claims I wonder how he suggests that, as a descendant of the conquered, I should express my gratitude. Should I, as some of my ancestors did when Britain ruled India, touch Jenrick’s feet? Maybe he could gather us, the children of the conquered, in Westminster Hall and get us to do just that. It would make great television.

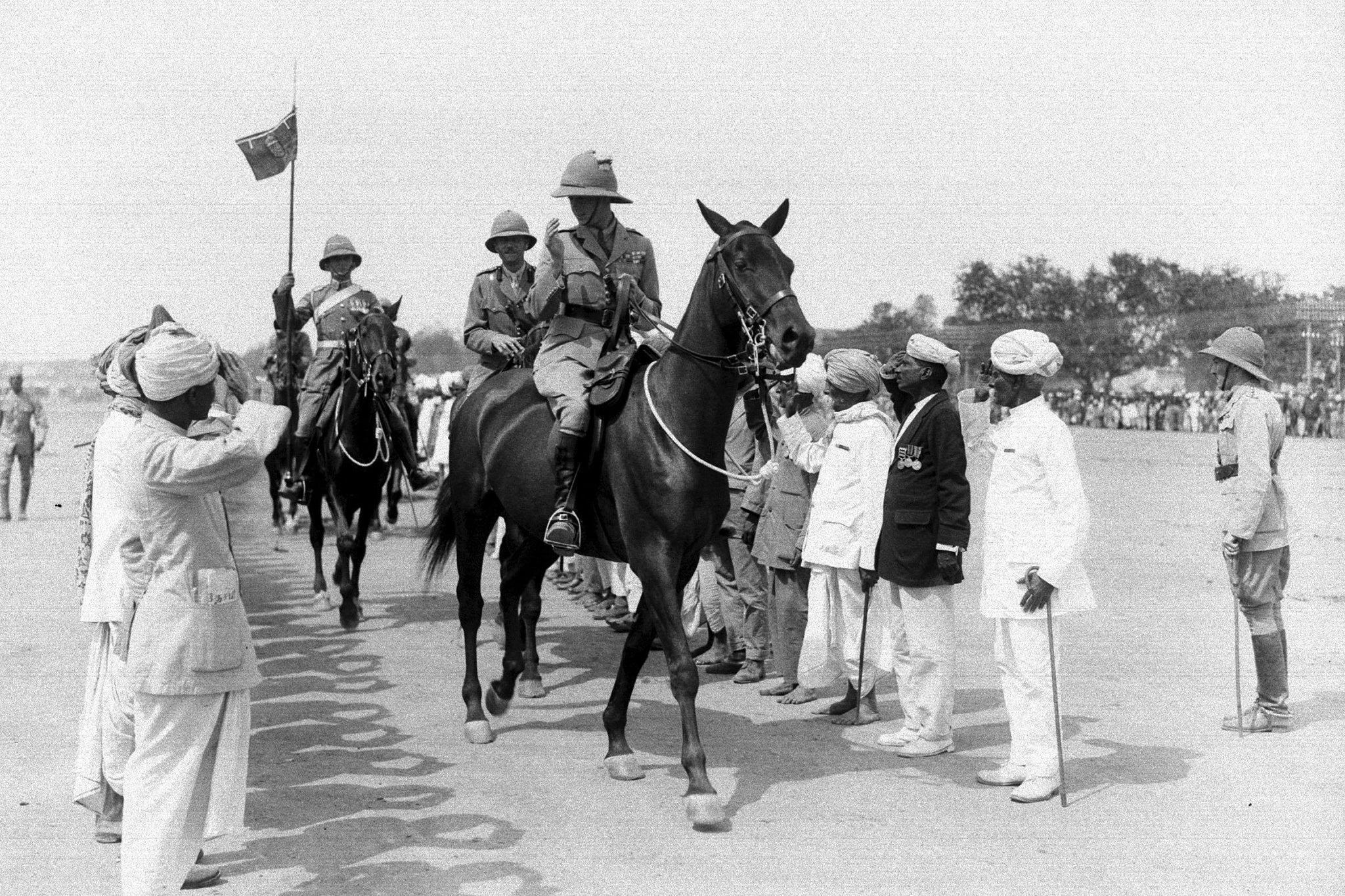

The fact is the empire was meant to make profits for the conquerors – and it did. While there was a collateral benefit, for instance, railways in India constructed to better facilitate the transportation of British troops necessary to maintain control, it was never meant to be and was never a sort of Victorian NGO.

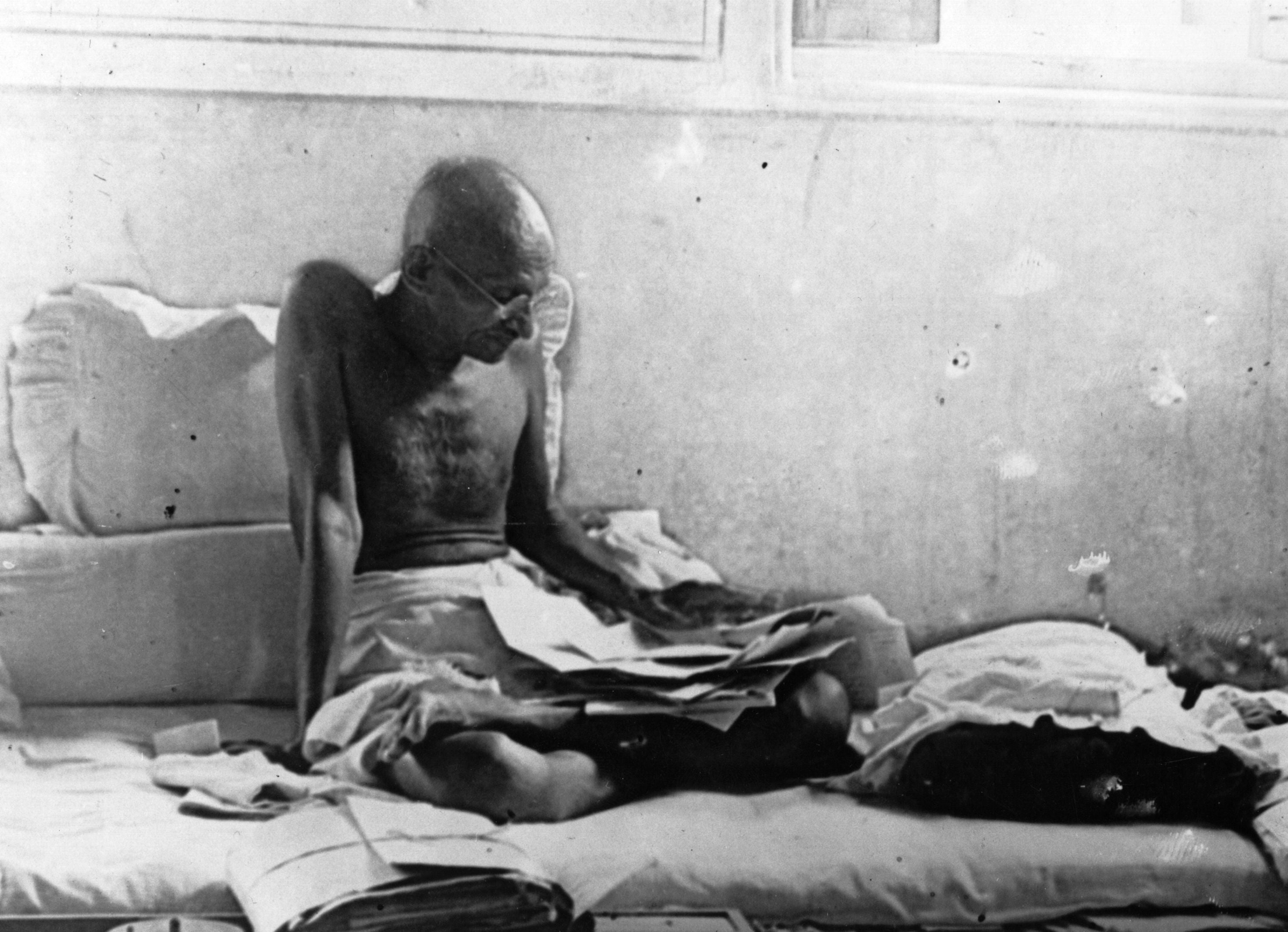

The British empire’s “success” story was, as Norman Manley, Jamaica’s first and only premier put it, in nurturing a “sense of inferiority in the governed”. Jawaharlal Nehru, India’s first prime minister, put this well when he wrote that “most of us accepted it as natural and inevitable” that Indians were second rate. “Greater than any victory of arms or diplomacy was this psychological triumph of the British in India”.

The problem for Jenrick and his ilk is that, unlike Manley and Nehru, today’s generation no longer accepts they are inferior to whites. They want to reclaim their history and present it as they see it, rather than as the version that is presented to them. In the process, they are discovering some very troubling facts that need to be acknowledged, not denied. I accept that the descendants of the conquerors cannot be asked to apologise for their ancestors or pay compensation. But they need to understand what their ancestors did and not provide excuses for the dark deeds or present an edited version which is far from the whole truth.

Unless they do, the process of reinventing this country into a truly multi-racial society will not be complete. Until we recognise the hard part of our collective history, there will always be a risk of going backwards and undoing all the progress that has been made since I arrived in 1969.

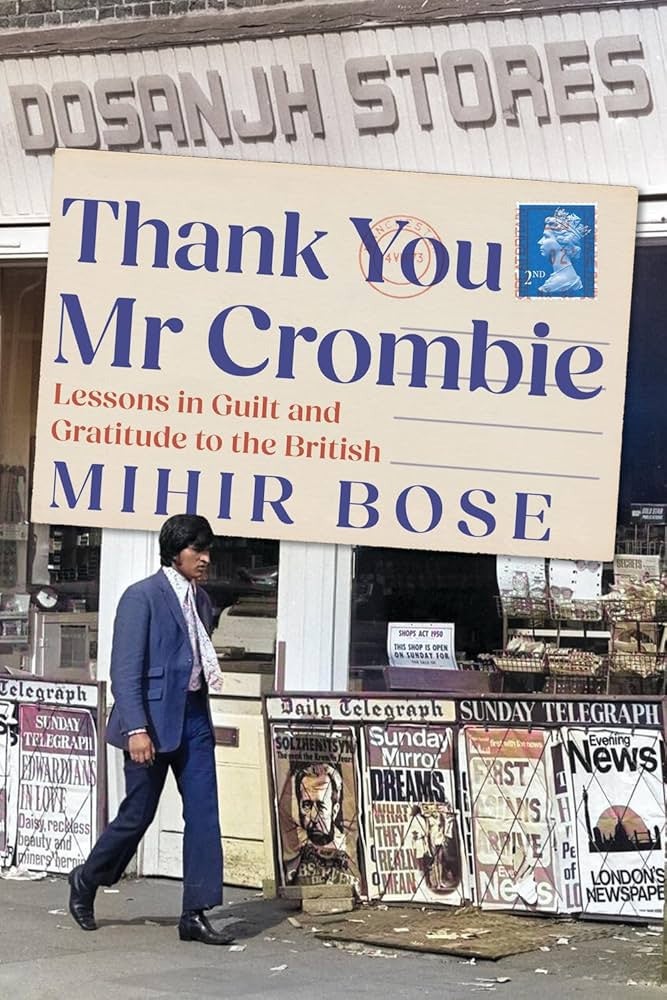

Mihir Bose is the author of ‘Thank You Mr Crombie: Lessons in Guilt and Gratitude to the British’ (Hurst, £25)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments