Stephen Lawrence 25 years on: What happened and was this really a murder that changed a nation?

Some say it changed the UK, but The Independent has heard claims that 'institutional racism' still lurks within some police forces

For a murder that changed a nation, it received precious little attention when it first happened.

On the evening of April 22 1993, 18-year-old aspiring architect Stephen Lawrence was set upon by a pack of white, racist youths as he waited at a bus stop in Eltham, south-east London.

At first it seemed the young black man might survive. He managed to break free from his attackers and run a distance of some 222 metres. But then he collapsed bleeding from two fatal stab wounds.

The racism was – or should have been – obvious from the start.

Before they charged at their prey, the killers had shouted: “what, what n****r?”

Among their number was David Norris, later caught by a police surveillance camera fantasising about being able to “skin a black c*** alive”. And Gary Dobson, seen by the same camera strutting about with a huge knife while boasting of confronting another “n****r”.

Yet the first national journalist to reach the grieving Lawrence family was not a specialist in crime or race relations.

It was The Independent’s then environment correspondent Nick Schoon, summoned by Stephen’s father Neville, who had done some plastering work on the journalist’s home (a coincidence that was to recur.)

Perhaps significantly, Mr Lawrence had felt the need to explain that his son was serious about his A-Level studies, that “he wasn’t into fighting one bit”.

The resulting story was tucked away on page four, “edited,” as Schoon recalled it, “Into a middling-length, inside-page piece about the latest run of racist murders in Greenwich.”

Twenty-five years ago, it seems, racist murders were not front page news.

In 1993, to get the attention of the press and the public, the Lawrence family and their supporters repeatedly had to show that Stephen was a “clean-living, honest young man with ambitions,” and “not a gangster”.

It seems that on the night of the murder, one Metropolitan police officer formed the view that this was a drug-related killing.

The day after the murder, a letter giving the names of Norris, Dobson and two other suspects was left in a phone box. Within days of the stabbing, dozens of people had given the names of the suspected killers to police.

But in July 1993 charges against five arrested suspects were dropped.

There were suspicions that the investigation had been hampered by a possibly corrupt relationship between one detective and Norris’ gangster father.

But more fundamentally there was the problem later defined by the inquiry judge Sir William Macpherson as “institutional racism”: “the "collective failure of an organisation to provide a professional service … through unwitting prejudice, ignorance, thoughtlessness and racist stereotyping which disadvantage minority ethnic people".

It took six years and a public inquiry before Sir William published that conclusion in February 1999.

To get there took a visit from Nelson Mandela, who met Neville and Doreen Lawrence and publicly stated that their son’s murder showed “It seems black lives are cheap”.

It took the failure of Neville and Doreen’s private murder prosecution, and an inquest which reached the verdict that Stephen had died in a “completely unprovoked racist attack”, despite the swaggering suspects’ refusal to answer questions.

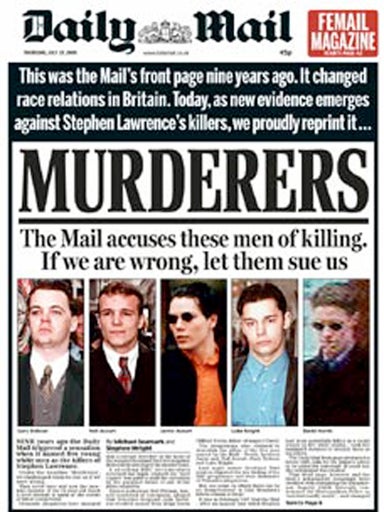

Most striking of all, though, it took the Daily Mail’s front page of February 14 1997, the day after the inquest. “MURDERERS,” it shouted, above the pictures of the mute inquest attendees. “The Mail accuses these men of killing. If we are wrong, let them sue us.”

Neville Lawrence had also done plastering work on editor Paul Dacre’s house.

Initially some rivals suspected a cynical stunt. Now it can be seen that whatever else the Mail got wrong, that front page was an act of astonishing moral and journalistic courage, with profound consequences.

Seven months later, in July 1997, Labour home secretary Jack Straw announced that Macpherson, a retired High Court judge, would chair a public inquiry into the Lawrence murder.

It was held, not in some hallowed legal chamber, but in Hannibal House, above south London’s Elephant and Castle shopping centre.

At times, the drama surrounding the inquiry was extraordinary. When the five murder suspects left after giving evidence, they were pelted with eggs, hot coffee and bottles. David Norris responded by trading punches with some of the 200 demonstrators.

But nothing compared with the drama of Sir William’s report, with its conclusion of “institutional racism” within the Metropolitan Police.

Endorsing the report in the Commons in February 1999, Mr Straw looked directly at Doreen and Neville Lawrence, sitting in the public gallery, and praised their “dignity, courage and determination”.

He told them that he wanted the Macpherson report to be “a watershed in attitudes towards racism, a catalyst for permanent and irrevocable change, not just across our public services, but across the whole of society.

“Upon this report,” said Mr Straw, “We must build a lasting testament to Stephen.”

As the 25th anniversary approaches, Stephen’s death is being marked by interviews, analysis, a BBC documentary series. And yet it still might be possible to overlook just what a watershed it became.

The Macpherson report didn’t just coin the new phrase "institutional racism".

It made 70 recommendations, and 67 of them had produced specific changes in practice or law within two years of the report’s publication.

So many of these are now so taken for granted – or so bemoaned as “political correctness” – that it may come as a surprise to learn that they have not been around forever.

Before the Stephen Lawrence murder and Macpherson report, the police, immigration service and many other public bodies were exempt from race relations legislation. A year after Macpherson, the Race Relations (Amendment) Act placed a legal obligation on public bodies including the police to promote good relations, while protecting any victims they might discriminate against.

The Macpherson report defined a racist incident as “any incident which is perceived to be racist by the victim or any other person”. In so doing, it imposed a far stronger obligation on the police to investigate hate crime.

The creation of the Independent Police Complaints Commission in 2004 was a response to the Lawrence family’s deep frustration with the existing system and Macpherson’s recommendation that allegations against the police be investigated by a body that was truly separate from it.

Other recommendations led to the introduction of detailed recruitment and retention targets for black and Asian police officers.

And beyond the police, beyond its specific recommendations, the Macpherson report prompted wider soul-searching. Across the country, individuals, institutions, and private companies came to ask themselves whether they too might be institutionally racist.

The report may not have introduced the concept of “diversity”, but it did help make it a buzzword.

There was a “deep-seated cultural change”, Straw claimed in 2013. “The pervasive, open racism of the fifties and sixties, the pernicious, sniggering racism of the seventies, eighties and nineties is gone.”

If that suggests something of a Hollywood ending, it should be said that in 2018, there remain more than a few voices suggesting that the Stephen Lawrence story shouldn’t be quite be so neatly packaged.

Speaking to The Independent on Monday, Tola Munro, president of the National Black Police Association (NBPA), revealed: “I was having a private conversation with a chief constable. He said of his own force that it was institutionally racist. That was last month.”

Mr Munro said this, not to deny that progress has been made, but to show that it has been “patchy”.

And so he praised the good work done by the police forces of Bedfordshire, West Midlands, and Avon and Somerset.

But he also pointed out that the Independent Office for Police Conduct is currently investigating claims of discrimination at Cleveland Police - allegations that the NBPA suspects might amount to “institutional racism” - 25 years after the murder of Stephen Lawrence.

Other relatively recent employment tribunal cases, said Mr Munro, suggested that ethnic minority police officers were still being discriminated against because of the colour of their skin.

Among them were cases involving London police officers. The black, gay police officer Kevin Maxwell complained of being “hounded out” of the Metropolitan Police in 2012 after raising concerns about racist and homophobic behaviour by some counter-terrorism officers

Carol Howard, “poster girl” for Scotland Yard’s Olympics security operation in 2012, was ruled by a tribunal in 2014 to have been victimised because of her race.

Being used as a “token”, Ms Howard told the tribunal hearing, even stretched to the irony of having to drive Doreen Lawrence from Brixton to Kensington “to demonstrate to [her] that the organisation had come a long way as here I stood as a successful black female officer."

Such cases, Mr Munro said, point to a wider problem of police forces failing to retain and progress BAME officers.

Only about two per cent of officers of assistant chief constable rank or above are BAME, he said, and the UK has only ever had one black chief constable.

“You have got to look at those figures,” says Mr Munro, “And ask the reason for them, and consider the possibility that your processes and behaviour might be institutionally racist.”

It is a controversial view.

Metropolitan Police Commissioner Cressida Dick has told the BBC: “The Met is a completely different organisation to the one it was when Stephen was killed. We're much more diverse. We are so much more open.

“The Stephen Lawrence inquiry and the endless campaigning [of the Stephen Lawrence family] has helped change the face, professionalism and attitude of the Metropolitan police service.”

A Scotland Yard spokesman told The Independent: “Our officers' response, when a small minority of their colleagues are found to be guilty of racist behaviour, can leave others in no doubt that there is no place for racism within the Metropolitan Police.

“In September 2016 the Equality and Human Rights Commission published the findings of their investigation into how the Met managed internal complaints of discrimination. The Met has delivered a significant number of improvements.”

Mr Munro further suggested that nationwide, progress has also been patchy when it comes to operational policing: while the police are now “much stronger” at dealing with hate crime, the statistics are far less encouraging when it comes to stop and search.

In February 1999 Jack Straw had told the Commons he hoped such powers would be used “more effectively and fairly”.

But in October 2017 new figures revealed that black people were eight times more likely to be stopped and searched than whites. That was actually worse than the disparity in the year Stephen Lawrence was killed: in 1993 a black person was five times more likely to be stopped and searched.

For Mr Munro, there was a clear conclusion: those forces which have been willing to confront the implications of being called institutionally racist, have been able to progress.

“But,” he said, “Those forces which have avoided it or refused to speak about it are, sadly, still in denial.”

“That,” he added, “Is the lived experience of my members. When there is an operational necessity, with an issue like knife crime, a chief officer might say ‘We want our BAME officers out there speaking to people’.

“But then we go back to being invisible, apart from dismissals.

“I find myself having to say the same thing over and over again. It makes me quite frustrated and very disappointed.”

And it does indeed seem that major anniversaries of the Stephen Lawrence murder have developed an unfortunate tendency to bring forth what could be seen as glaring examples of just how far from perfect the situation remains.

In 2013, 20 years after the murder, Surrey had a new Police and Crime Commissioner, Kevin Hurley. Three months after being elected on a “zero tolerance” ticket and two years after leaving the Metropolitan Police, the ex-Detective Chief Superintendent told a local newspaper the Macpherson report was the result of “post-colonial guilt”.

In 2003, 10 years after the murder, BBC Panorama reported on the experiences of a reporter who had gone undercover as a police trainee. Mark Daly found himself being told by a fellow recruit that Stephen Lawrence had deserved to die.

“He f***ing derserved it and his mum and dad are a f***ing pair of spongers,” the trainee constable said. “The Macpherson report … a kick in the bollocks for any white man.”

Mr Daly has now revealed how he showed the footage to Doreen Lawrence in a BBC editing suite.

Stephen Lawrence’s mother, he said, had not seemed surprised. She had simply said: “It’s just like we thought.”

Doreen Lawrence, made Baroness Lawrence in 2013, may never have accepted the injustice meted out to her son, but she has developed a steely realism about it.

In 2012 she had the satisfaction of seeing Dobson and David Norris convicted of murder, after changes to the double jeopardy rules – made partly because of Stephen’s case - allowed them to be tried on new evidence.

That, though, left the widespread impression that three other suspected racist killers had evaded proper justice.

And this month, in an interview to mark the 25th anniversary, Lady Lawrence suggested the continuing investigation into her son’s murder should now be closed if it really had no more worthwhile leads to investigate.

“I don't think they have any more lines of inquiry,” Lady Lawrence said. “If they've come to the end, they should be honest, say they've come to an end and stop.”

It seemed, perhaps, to suggest that a nation could change, and that some progress, however faltering or limited, could be made - but that after the racist murder of a teenager at a south London bus stop, there were some things that could never be put right.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments