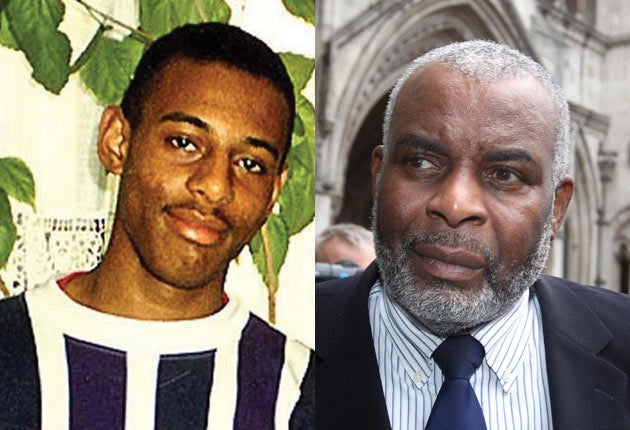

Stephen Lawrence's murder left a 'shrunken, shattered family'

The phone rang unusually early on a weekday morning in April 1993. It was Neville Lawrence, a tall, quiet man who, a few years earlier, had spent a week or two plastering our home in Greenwich, south-east London.

Now Neville was ringing because his 18-year-old son Stephen had been stabbed the previous night – murdered. And he needed the world to know.

So I set off east, through spring sunshine and a sense of dread, to the big estate in Eltham where the Lawrence family lived. I arrived, rang the bell and was ushered in. Friends and relatives were already there to support the shrunken, shattered family. But it was quiet: hushed voices, no weeping. Endless rounds of cups of tea and coffee. The men were in the small, neat living room, the women in the kitchen. Neville and Doreen, Stephen’s mother, were both in shock during those very first hours of a nightmare which would roll on for decades. Doreen seemed barely able to speak. Neville told of a neighbour’s late-night knock on the door – his son had heard that Stephen had been stabbed.

Then the rush to hospital, the waiting, the doctor who told the parents they had tried their hardest but that there was nothing they could do to save their son.

They had seen Stephen’s body laid out in the small hours. Now the sun was up but their sleepless night continued. Neville had since heard, from Stephen’s friend Duwayne Brooks, that it was a group of white youths who had crossed a road and descended on his son.

Looking back, two things are striking. A few hours after the family left their son’s body in hospital, there were no police or authority figures with them and none arrived during the time I was there. Police forces put less effort into victim support in those days. To me, back then, the absence of any officers seemed uncaring. The Lawrence family appeared to have been left isolated in their grief by the wider community.

The second thing: why had Neville called a journalist so soon?

Amid his shock and unimaginable grief, Neville must have feared that the police, the state, the establishment, might fail in finding and convicting his boy’s killers. He hoped that doing anything he could to tell the world about the murder would help him to get justice.

Family photographs stood on a sideboard – an image of Stephen as a young teenager, not the tall, confident-looking youth in the striped sports shirt that is always shown on television today.

Neville explained that Stephen was serious about his A-level studies at Blackheath Bluecoat School. He wanted to be an architect and avoided trouble. “He wasn’t into fighting one bit,” is the one direct quote from my talk with Neville that made it into print the next day. My interview with Neville, combined with another reporter’s write-up of a police press conference, was edited into a middling-length, inside-page piece about the latest in a run of racist murders in Greenwich. None of the national press gave much space to the killing the following day, but a campaign gradually built up around the parents’ long, agonising search for justice.

This dignified, quietly spoken man gradually became grey and stooped in television images, while those who killed the Lawrences’ son so quickly went free.

Neville and Doreen Lawrence had no idea that bright April morning that their son’s murder would consume them for two decades – through the court cases, the Macpherson inquiry, the new forensic evidence and prosecution.

Doreen spoke today. It was time for people to stop thinking of her son as a black victim, she said. He was “a bright, beautiful young man any parent would have been proud of”.

Nicholas Schoon was The Independent’s Environment Correspondent