Facial recognition to be rolled out across London by police, despite privacy concerns

Only a handful of arrests were made in almost three years of trials but police insist technology is ‘fantastic crime-fighting tool’

Police are to start using controversial facial recognition across London, despite concerns over the technology’s accuracy and privacy issues.

Eight trials carried out by the Metropolitan Police between 2016 and 2018 resulted in a 96 per cent rate of “false positives”, and only eight arrests resulted from a facial recognition match.

Privacy campaigners have vowed to launch new legal challenges against its use and called the move a “serious threat to civil liberties in the UK”.

But a senior officer insisted live facial recognition (LFR) was a “fantastic crime-fighting tool”.

Assistant commissioner Nick Ephgrave said every deployment would be “bespoke” and target lists of wanted offenders or vulnerable missing people.

“LFR is only bringing technology to bear on a policing activity since policing began,” he added.

“We brief officers showing them photographs of wanted people, asking them to memorise that photograph and see if they can spot that person on patrol ... what LFR does for us is make that process more efficient and effective.”

Mr Ephgrave said the technology would be primarily used for serious and violent offenders who are at large, as well as missing children and vulnerable people.

Police said any potential “alerts” would be kept for one month, while watchlists will be wiped immediately after each operation.

The system can support lists of up to 10,000 wanted people but officials said they will be targeting specific groups in set areas because of “lawfulness and proportionality”.

Mr Ephgrave said LFR “makes no decisions” alone, and works by flagging potential facial matches from live footage to the police database.

Officers then judge whether the person could be the same and decide whether to question them in order to establish their identity.

“Most of the time they will want to do that – have a conversation, establish credentials, and either make a positive identification and arrest or let them move on,” Mr Ephgrave said.

“We want to make sure these deployments are effective in fighting crime but are also accepted by the public. Londoners expect us to deploy this technology responsibly.”

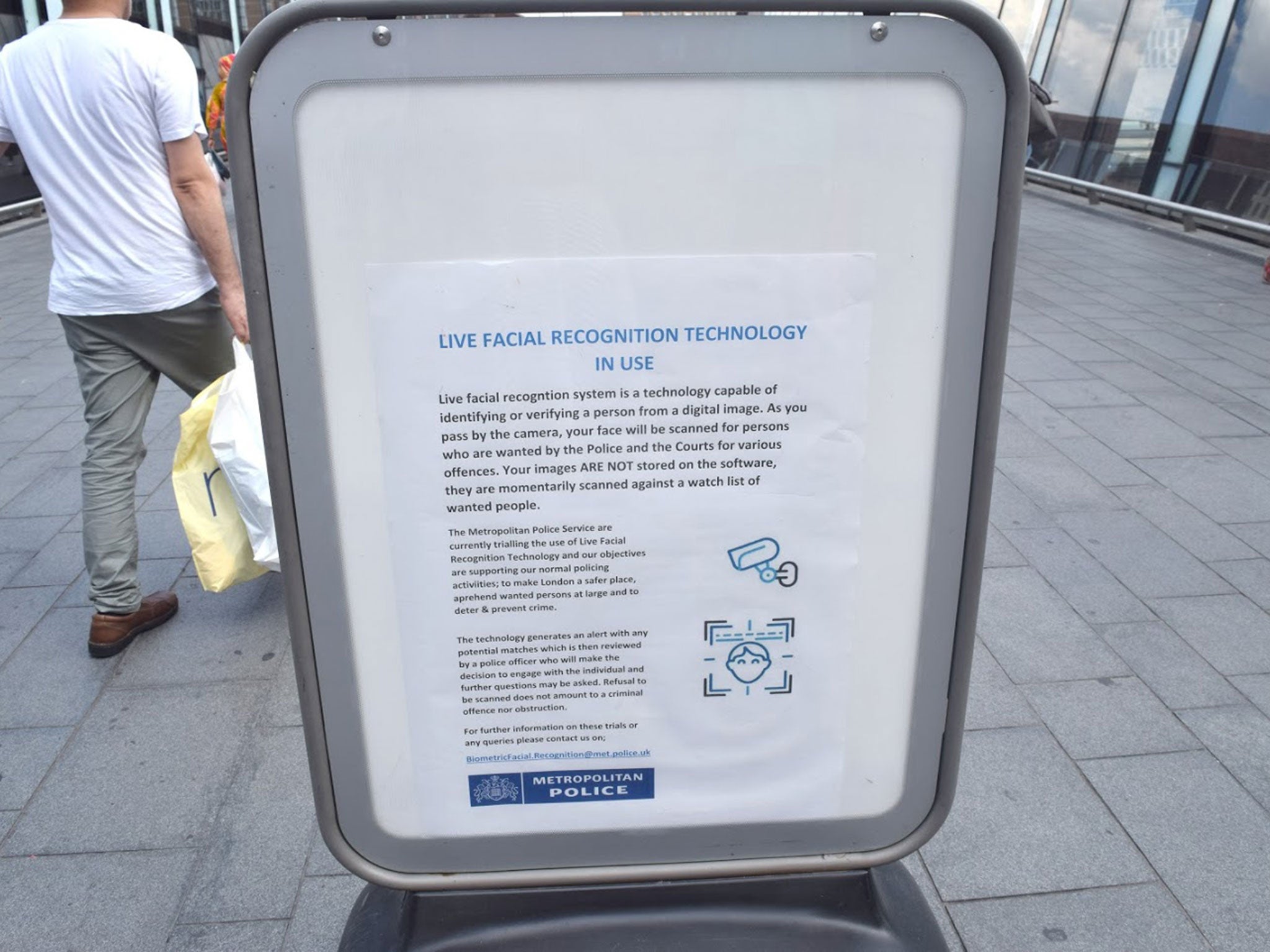

He insisted that deployments would be “overt”, with members of the public being warned about scanning using signs and leaflets handed out by officers.

But Scotland Yard promised the same tactics at a series of trials where The Independent found people were unaware that they had been caught on facial recognition.

The force said its system was “completely closed” and will use mobile police cameras rather than existing CCTV.

Officers acknowledged that algorithms were “marginally less accurate” when scanning women but denied any racial bias in the technology being used in London.

Mr Ephgrave claimed police had been given a “strong legal mandate” to use facial recognition by a legal challenge that ruled that South Wales Police had used the technology lawfully.

But the landmark case is being appealed and only assessed two specific deployments, and the information commissioner warned that it “should not be seen as a blanket authorisation for police forces to use LFR systems in all circumstances”.

Issuing a legal opinion in October, Elizabeth Denham said: “Police forces must provide demonstrably sound evidence to show that LFR technology is strictly necessary, balanced and effective in each specific context in which it is deployed.

“A high statutory threshold that must be met to justify the use of LFR, and demonstrate accountability, under the UK’s data protection law.”

She added: “Never before have we seen technologies with the potential for such widespread invasiveness.”

Ms Denham warned that the lack of a specific legal framework for facial recognition created inconsistency and increased the risk of data protection violations.

The Metropolitan Police said it could not give journalists its budget for the technology, after The Independent revealed it spent more than £200,000 on initial trials that resulted in no arrests.

A small number of arrests were made at later deployments, but police were heavily criticised for fining a man after he swore at officers who stopped him for covering his face in Romford.

Eight trials carried out in London between 2016 and 2018 resulted in a 96 per cent rate of “false positives” – where software wrongly alerts police that a person passing through the scanning area matches a photo on the database.

Two deployments outside the Westfield shopping centre in Stratford in 2018 saw a 100 per cent failure rate and monitors said a 14-year-old black schoolboy was fingerprinted after being misidentified.

Scotland Yard said that during almost three years of trials only eight arrests were made as a direct result of the flagging system.

Offences included robbery, malicious communications, kidnapping and assaulting police. One man arrested for breaching a non-molestation order was later jailed.

Johanna Morley, Scotland Yard’s senior technologist, described the NEC NeoFace software as “extremely accurate”.

She said that for people walking past cameras who are on a watchlist, there is a 70 per cent chance of an alert, and only a 0.1 per cent chance for innocent members of the public.

But Clare Collier, the advocacy director for campaign group Liberty, called rolling out the technology a “dangerous, oppressive and completely unjustified move”.

“Rolling out an oppressive mass surveillance tool that has been rejected by democracies and embraced by oppressive regimes is a dangerous and sinister step,” she added.

Silkie Carlo, director of Big Brother Watch, said: “This decision represents an enormous expansion of the surveillance state and a serious threat to civil liberties in the UK.

“It flies in the face of the independent review showing the Met’s use of facial recognition was likely unlawful, risked harming public rights and was 81 per cent inaccurate.

“This is a breathtaking assault on our rights and we will challenge it, including by urgently considering next steps in our ongoing legal claim against the Met and the home secretary.”