Scientists find strongest biological material in the world in microscopic algae cells

It has been discovered that the shells of the tiny cells have the highest strength-to-weight ratio of any biological material

Your support helps us to tell the story

This election is still a dead heat, according to most polls. In a fight with such wafer-thin margins, we need reporters on the ground talking to the people Trump and Harris are courting. Your support allows us to keep sending journalists to the story.

The Independent is trusted by 27 million Americans from across the entire political spectrum every month. Unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock you out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. But quality journalism must still be paid for.

Help us keep bring these critical stories to light. Your support makes all the difference.

American scientists have discovered the strongest biological material in the world in the shells of microscopic algae cells called diatoms.

A team of researchers from the Division of Engineering and Applied Science at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech), led by Julia Greer, made the important discovery while studying diatoms, tiny single-celled algae organisms which can be as small as twenty microns across.

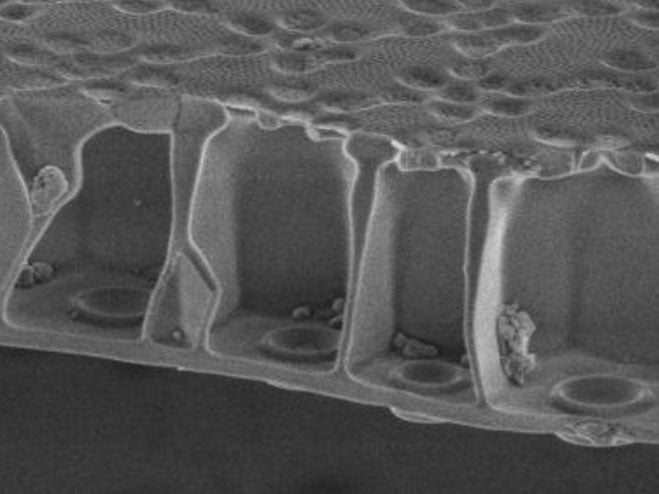

Diatoms, which can vary in shape, are encased within cell walls made of silica called frustules, which were the focus of the group's recent study.

Using painstaking techniques, the researchers built tiny 'beams' out of frustules, which they then subjected to bend tests.

Despite their tiny size, the team were suprised to discover that frustules have the highest strength-to-weight ratio of all known biological materials, finding they are much stronger than bone, teeth or antler.

Frustules are covered in tiny holes that look a little like honeycomb, which scientists believe allow diatoms to absorb nutrients from their surroundings.

However, as Phys.org reports, Greer and her team believe that these holes also strengthen the diatom's structure, by stopping the spread of cracks once the organism comes under pressure.

She said: "Silica is a strong but brittle material. For example, when you drop a piece of glass [which is usually mostly made up of silica], it shatters."

"But architecting this material into the complex design of these diatom shells actually creates a structure that is resilient against damage," she said.

Building on their discovery, the team now intends to take inspiration from the unique structure of diatoms to try and build similarly resistant structures out of other materials.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments