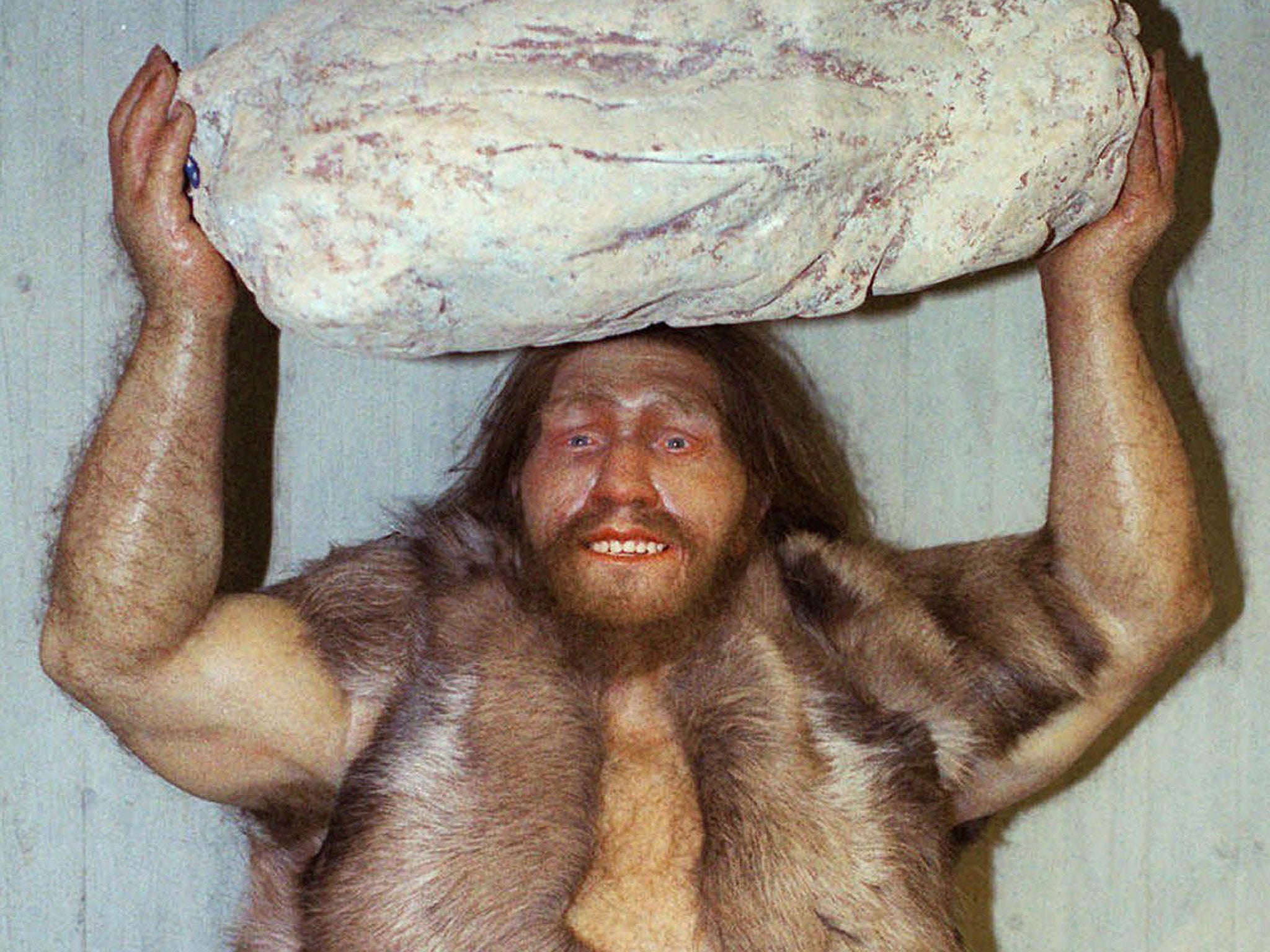

Neanderthal genes linked to diseases in modern day humans including type two diabetes

The likelihood of people developing diseases including type two diabetes and Crohn's could be affected by genes inherited from Neanderthals

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The genetic makeup passed down to modern humans when they mated with Neanderthals continues to affect us, a new study has shown.

The research published in the journal ‘Nature’ reveals that the likelihood of non-African Homoe sapiens developing conditions, particularly auto-immune disorders, can be determined by Neanderthal alleles.

The diseases include: type two diabetes, Crohn's disease, lupus and biliary cirrhosis

The genes are also associated with people who smoke, as well as keratin filaments – the fibrous protein that make skin, hair and nails tough.

This trait may have helped provide newcomers from Africa thicker insulation against the cold European climate.

Researchers believe between two per cent and four per cent of the genetic code of Europeans and Asians derives from interbreeding between the two Homo sub-species, who existed simultaneously until around 30,000 years ago.

People indigenous to sub-Saharan Africa, whose ancestors did not migrate out of the continent when the sub-species co-existed, carry little or no Neanderthal DNA according to research.

To obtain the results, scientists from Harvard Medical School compared the genes from the 50,000 year old toe bone of a Neanderthal woman with the DNA of 846 people of non-African heritage, and 176 people from sub-Saharan Africa.

Professor David Reich, from Harvard Medical School in the US, who led the study, said:

“Now that we can estimate the probability that a particular genetic variant arose from Neanderthals, we can begin to understand how that inherited DNA affects us.

"We may also learn more about what Neanderthals themselves were like."

"It's tempting to think that Neanderthals were already adapted to the non-African environment and provided this genetic benefit to (modern) humans," Professor Reich said.

The team is following up the research by testing for Neanderthal mutations in a biobank containing genetic data from half a million Britons.

Professor Chris Stringer, a leading expert in human origins at London's Natural History Museum, said the findings added a new twist to the debate over how early modern humans related to Neanderthals and Denisovans, another subspecies cousin from Siberia.

He did not think it undermined current thinking about our ancestors' African origins.

“The genetic data also show there are thousands of DNA changes that are unique to Homo sapiens, and these distinctions are likely to have accumulated during the several hundred thousand years since Homo sapiens separated from the Neanderthal and Denisovan lineages as they evolved in Africa and Eurasia, respectively,” he said.

“Our genetic heritage is still largely from a recent African origin, despite the interbreeding with other human populations that undoubtedly occurred.”

Additional reporting by PA

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments