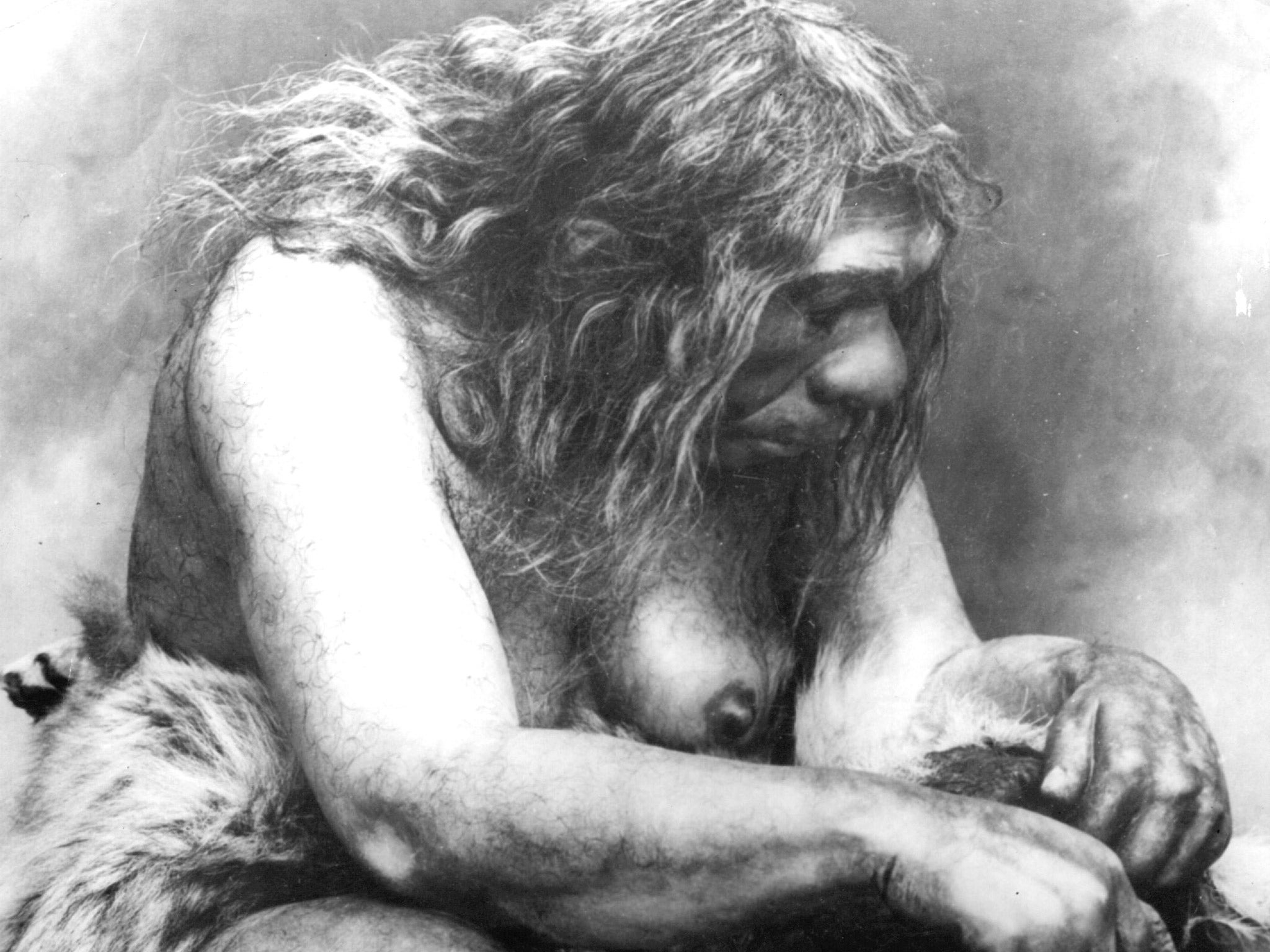

DNA from a 50,000 year old toe shows Neanderthals were highly inbred

The toe holds the clues to the truth about interbreeding between Neanderthals and other human sub-species

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A study has shown that Neanderthals took the idea of the close-knit family a little too far.

DNA taken from the 50,000-year-old toe bone of a Neanderthal woman has shown that she was highly inbred.

Experts believe that the inbreeding is the outcome of Neanderthal populations being very small.

Scientific tests revealed that her parents were either half-siblings who shared the same mother, an uncle and niece, an aunt and nephew, or a grandparent and grandchild.

Alternatively, they may have been double first cousins.

The DNA studies have now proved that Neanderthals and modern humans interbred, a question that scientists have disagreed over for years. In fact, it is currently estimated that between 1.5 per cent and 2.1 per cent of the genomes of modern non-African people can be traced to Neanderthals.

Although they made tools and weapons, it is thought that Neanderthals did not survive as a human sub-species in the same was a modern humans because they lacked the inventiveness and social structures that saw the latter flourish.

The findings published in the journal Nature come from the most complete blueprint of a Neanderthal genome – or genetic code – ever constructed.

To achieve their results, scientists sequenced the genome from DNA found in the toe of the Neanderthal woman whose remains were found in a Siberian cave in the Altai Mountains.

Neanderthals and Denisovans were also found to be closely related.

The study also identified at least 87 specific genes in modern humans that stand out as significantly different from any found in Neanderthals or Denisovans.

According to Dr Svante Paabo, who led the international team behind the project, the list of genes contains a “catalogue” of features setting modern humans apart from all other creatures, living or extinct.

“I believe that in it hide some of the things that made the enormous expansion of human populations and human culture and technology in the last 100,000 years possible,” he said.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments