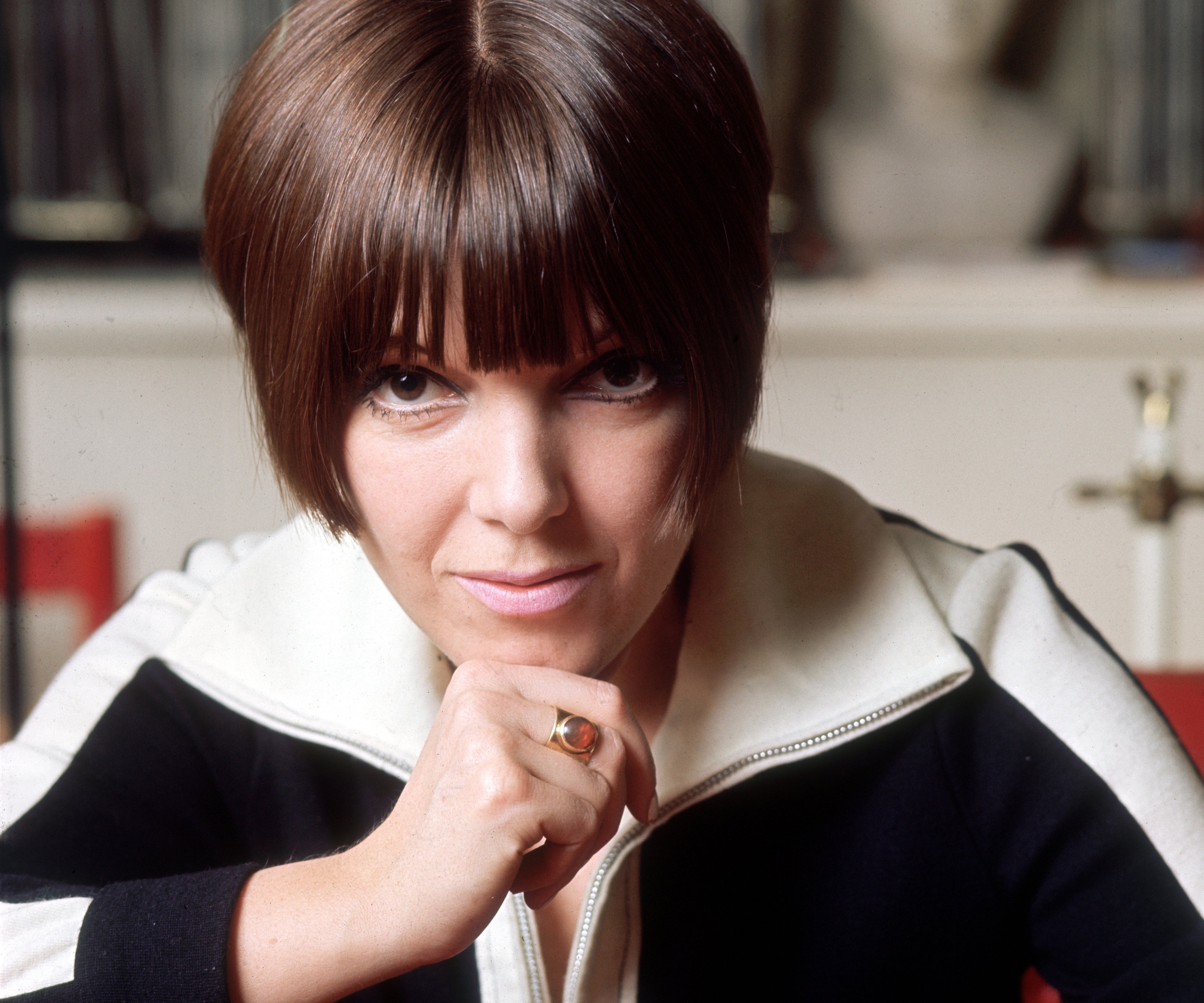

Mary Quant: Mother of the miniskirt

The scandalous hemlines of the British designer, who has died at the age of 93, helped turn the Sixties into a bold and vibrant era of fashion, writes Linda Watson.

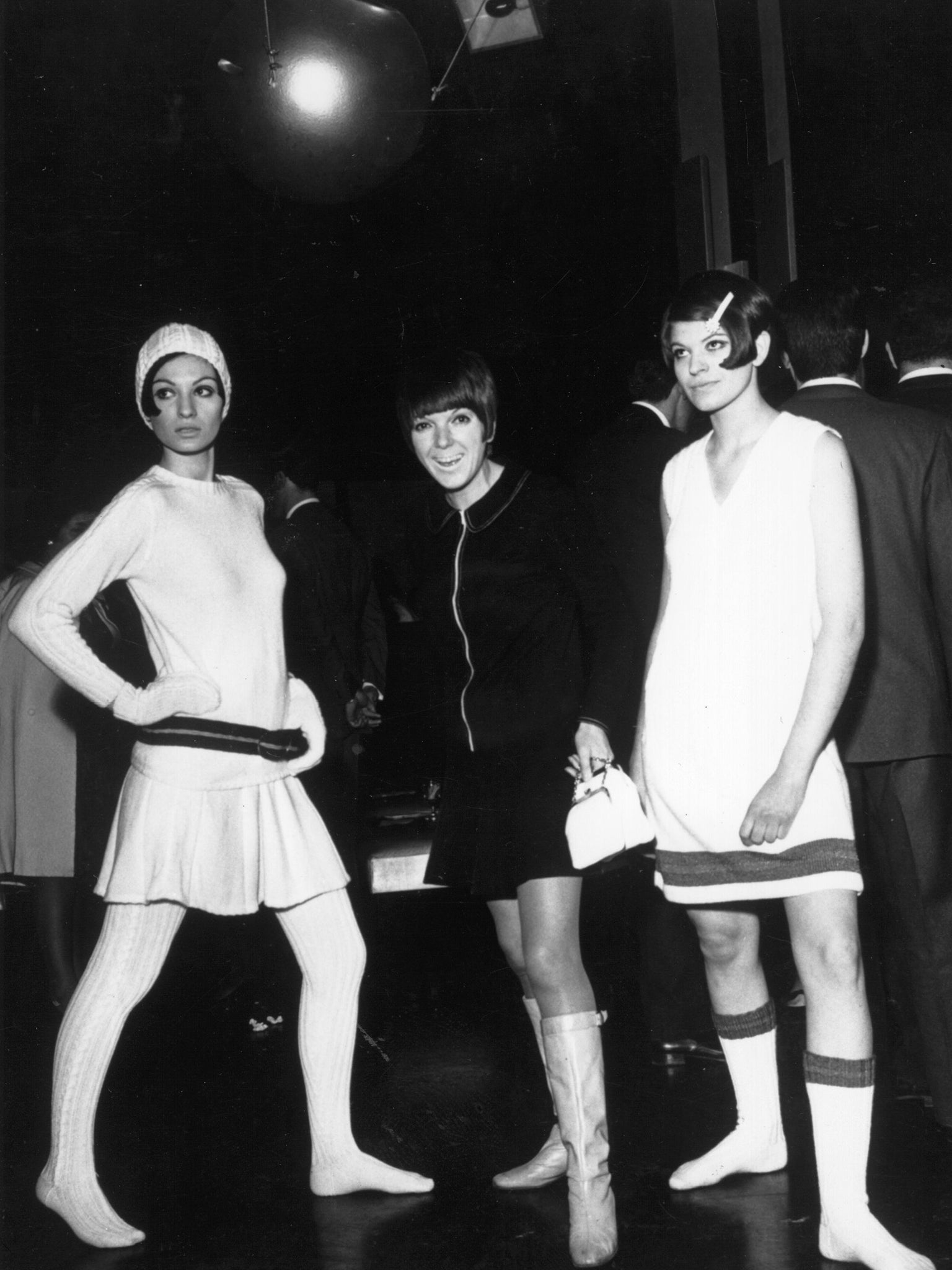

It wasn’t me or Courrèges who invented the miniskirt – it was the girls in the street who did it,” said Mary Quant of the revolutionary hemline she is widely credited with creating. The miniskirt was launched on King’s Road and immortalised in the Swinging Sixties, with Quant putting its success down to genetics: “The Chelsea girl had the best legs in the world. She had the courage to wear it.”

Despite it grabbing global press attention, not everyone was enamoured with the abbreviated skirt. Quant recalled how the stereotypical city gent, with his pinstriped suit and bowler hat, would beat Bazaar’s window with his brolly while shouting “Immoral!” and “Disgusting!”. Coco Chanel declared the miniskirt “indecent”. When Sophia Loren publicly claimed that the miniskirt had “destroyed the feminine mystique”, Quant replied: “Well, she’s built the other way up.”

Quant was born in Blackheath in 1934 to Welsh schoolteachers. Her mother was born in Kidwelly, her father in Merthyr, and each graduated with a first class honours degree from Cardiff University. Evacuated to a village in Kent with her brother Tony during the war, Quant recalled her earliest fashion memory as being in bed with measles at six years old and cutting the bedspread with nail scissors in order to transform it into a dress.

Her first successful encounter with needle and thread was an embroidered pillowcase she made for her mother at Christmas. When Quant was dispatched to a boarding school in Tunbridge Wells and presented with an exam question that asked her to choose between the Roundheads and the Cavaliers, Quant deemed it a no-brainer. “I came down strongly on the side of the Cavaliers, as they were more chic,” she said. On leaving school, she expressed her intention to pursue a career in clothes. Her parents were against the suggestion. Quant persuaded them to agree on the condition that she took an art teacher’s diploma.

Quant applied to and was accepted at Goldsmiths. Quentin Crisp was a resident model; Quant described him as “the most admired model and the most difficult to draw”. It was here that she met her future husband, the debonair Alexander Plunket Greene, in 1953 at a ball. Instantly besotted, she described him as “a 6ft 2in prototype for Mick Jagger and Paul McCartney rolled into one”. Quant was wearing “black mesh tights and strategically placed balloons” at the time.

Her suitor, who had a penchant for wearing his mother’s gold silk pyjama top paired with prune hipster pants and chelsea boots, could often be spotted with a copy of Tom Brown’s Schooldays under his arm or an enormous single lily in his hand. Plunket Greene invited Quant to Paris, claiming he was busking outside the George V Hotel. It was the beginning of a personal and professional partnership that would last until he died, at the age of 57, in 1990.

On graduating from Goldsmiths, Quant experienced a eureka moment when she apprenticed with a Mayfair milliner called Erik whose salon was situated next to Claridge’s. Earning £2 and 10 shillings per week, she started to think about fashion strategically – on the level of cost per wear. “It seemed so ridiculous making one hat for one woman to wear to Ascot that cost 30 quid,” said Quant. “It seemed obvious that clothes should be made by mass production.”

Despite his flamboyant persona, Plunket Greene was an astute entrepreneur with a sharp marketing mind, and according to Quant was “the greatest salesman ever”. They decided they wanted to work together rather than apart. “It makes your rows much more interesting,” Quant claimed. “They aren’t just about the housekeeping – or a wet towel.” Money wasn’t an issue.

Having met Archie McNair, a former solicitor who had opened Chelsea’s first espresso coffee bar, called Fantasy, they considered the possibility of a partnership. Plunket Greene had inherited £5,000 at the age of 21, and together with McNair decided to set up a business that combined fashion and food – Quant’s boutique, called Bazaar, would be on the ground floor, with a restaurant called Alexander’s in the basement.

Although McNair had previously run a photography studio, the trio used a mix of gut instinct and unfettered enthusiasm to stay afloat. “We didn’t know about mark-ups, we didn’t know about working capital,” said Quant. “Nobody told us we couldn’t do it – and we did it.” They paid the princely sum of £8,000 for the freehold on Markham House, a three-storey property at 138a King’s Road. When Bazaar opened its doors in 1955, there was already a long queue waiting patiently outside.

Alexander’s had opened a few weeks before. Word had spread. About to be unleashed was the style that Quant had succinctly summarised as “Very simple. Very bold.” A daisy logo, which Quant described as “the luck of my life”, became her symbol. Unable to find the kind of clothes she wanted, Quant metamorphosised from buyer to designer. She attended pattern-cutting classes and bought a sewing machine. Purchasing lengths of men’s suiting cloth from Harrods, Quant made tunic dresses to be worn with skinny sweaters underneath.

She would ask theatrical manufacturers to make tights in all colours. Quant persuaded knitwear producers to add another foot onto sweaters to turn them into dresses. “That was how the sack was born,” claimed Quant, “and it appeared in Paris a year later.” One of her most successful early creations – which sold in its thousands – was a white plastic collar designed to give a new look to a favourite black dress.

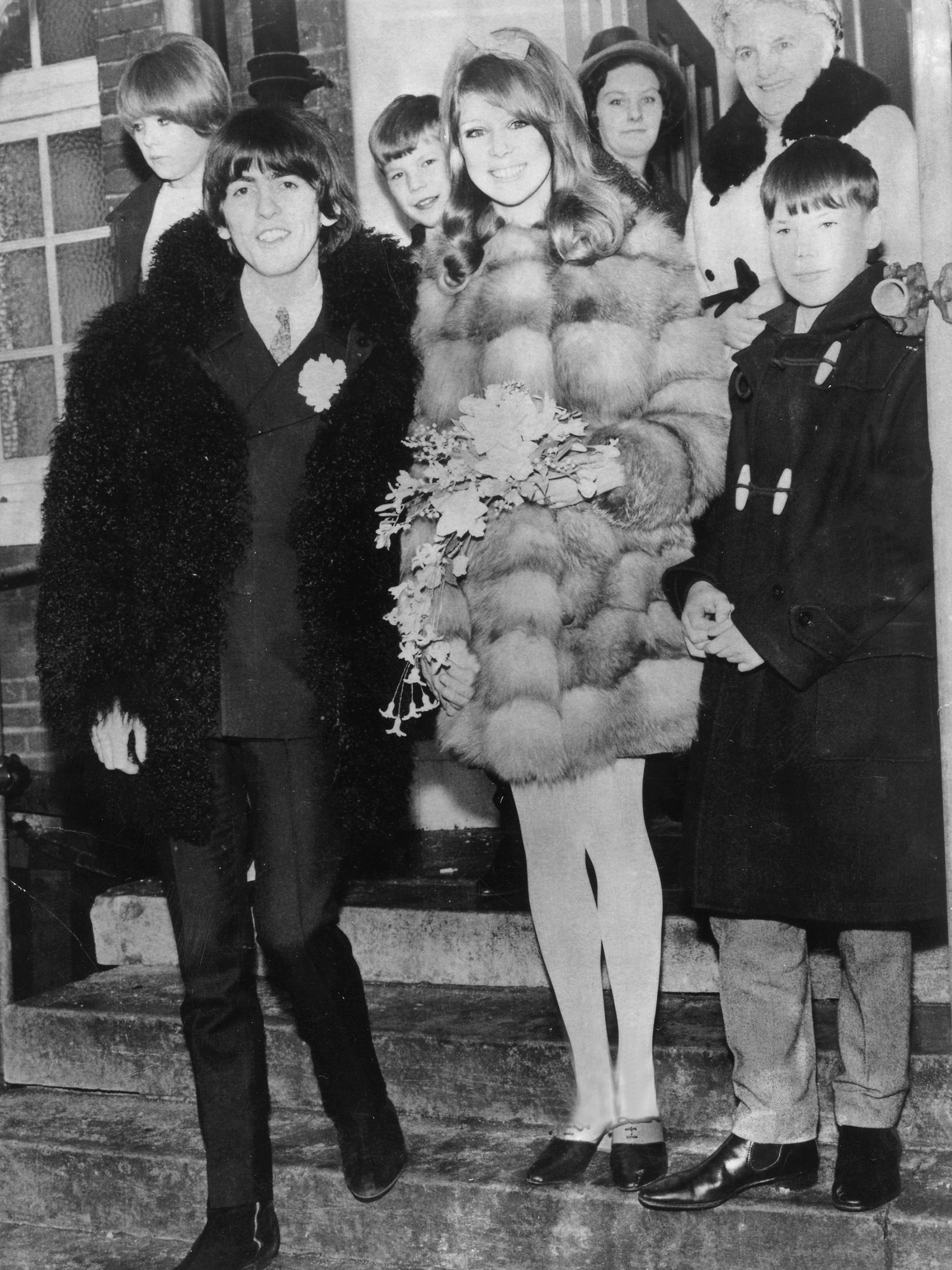

“I had my clothes described as dishy, grotty, geary, kinky, mod, poove and all the rest of it,” said Quant. “People either loved or hated it.” Celebrity customers including Brigitte Bardot, Leslie Caron and Audrey Hepburn frequented both the boutique and the restaurant. John Lennon was photographed wearing a Mary Quant peaked cap. When Pattie Boyd married George Harrison at the Epsom register office in January 1963, she wore a Mary Quant ensemble of silk dress and red fox fur coat. Quant was given the Sunday Times Award for “jolting England out of its conventional attitude towards clothes”.

The Quant agenda was one of discovery and reinvention. In 1963, the designer deployed the glossy properties of PVC, having fabrics dyed in “ginger, terracotta colour and Coleman’s mustard yellow” for her “Wet Look” collection. She then launched the Ginger Group – one of the earliest designer diffusion lines. Joining forces with America’s JC Penney, Quant became the first named British designer to be promoted throughout the States. At the age of 32, she was awarded an OBE and wrote her first autobiography, Quant by Quant.

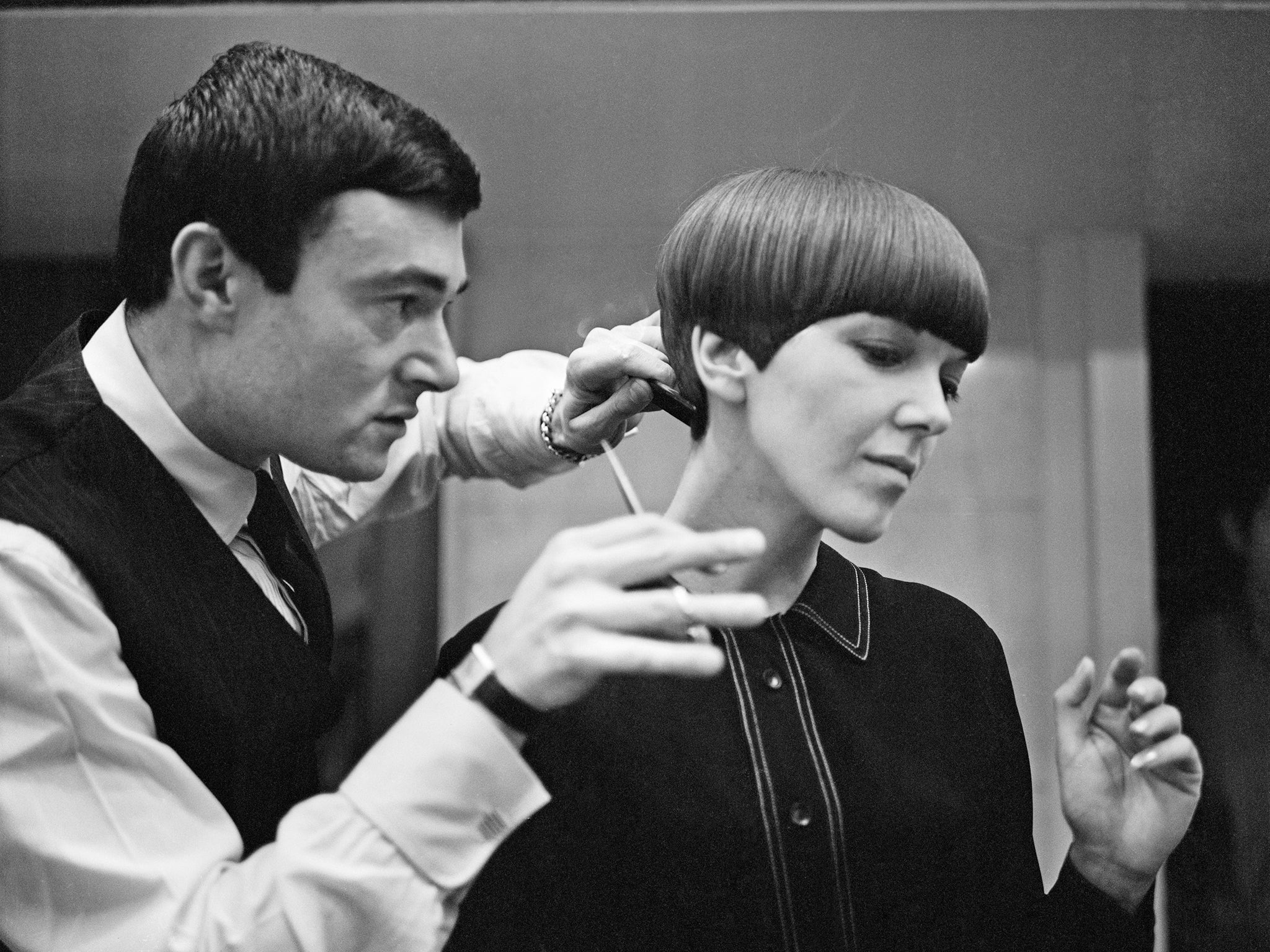

Within seven years of opening, the business had made over £1m and Quant’s designs were in 150 shops in the UK, 320 shops in the USA, and on sale globally in France, Italy, Switzerland, Kenya, South Africa, Australia and Canada. In 1963, Bazaar opened a second branch of her shop in Knightsbridge and, spotting a gap in the market, launched her own line of cosmetics. She was already having her hair cut at acute angles by rising star Vidal Sassoon, telling him decades later: “I made the clothes. You put the top on.” Taking a typically fresh approach to cosmetics, she created “paint boxes” in which make-up was presented as an artist’s palette. “Everything was there from head to toe except the face. The make-up was all wrong,” she said.

She watched Jean Shrimpton and Twiggy at close quarters, noting that they “used their face as a canvas, and painted on top, rather like an impressionist painter, with pots of colour and theatrical powder”. Her first make-up product consisted of cosmetic crayons in a tin. With an uncanny knack for brand-building, Plunket Greene injected humour into the product titles: eyeshadow was called “Jeepers Peepers”, gel cosmetics named “Jelly Babies”, there was a foundation called “Starkers” and a bra christened “Booby Traps”.

Two years after her son Orlando was born, in 1972, Quant visited Japan for the first time. The following year, the London Museum mounted a major retrospective titled “Mary Quant’s London”. Fashion was entering a new decade, but Quant continued to be a covetable brand. Long before it became de rigeur for designers to venture into lifestyle products, Quant launched her Mary Quant at Home line. By 1985, she had 72 shops in Japan.

In 2009, Quant’s favourite dress – called the Banana Split – was featured on a set of Royal Mail stamps, along with other icons of design including Concorde, Spitfire, the Anglepoise lamp and the London Underground map. When she wrote her second autobiography in 2012, three years before she was made a dame for services to the fashion industry, she looked back on her adventurous existence with an overwhelming sense of gratitude.

“I mostly felt, my God, what a marvellous life you had, you are very fortunate. I think to myself, you lucky woman – how did you have all this fun?”

Mary Quant, designer and entrepreneur, born 11 February 1930, died 13 April 2023