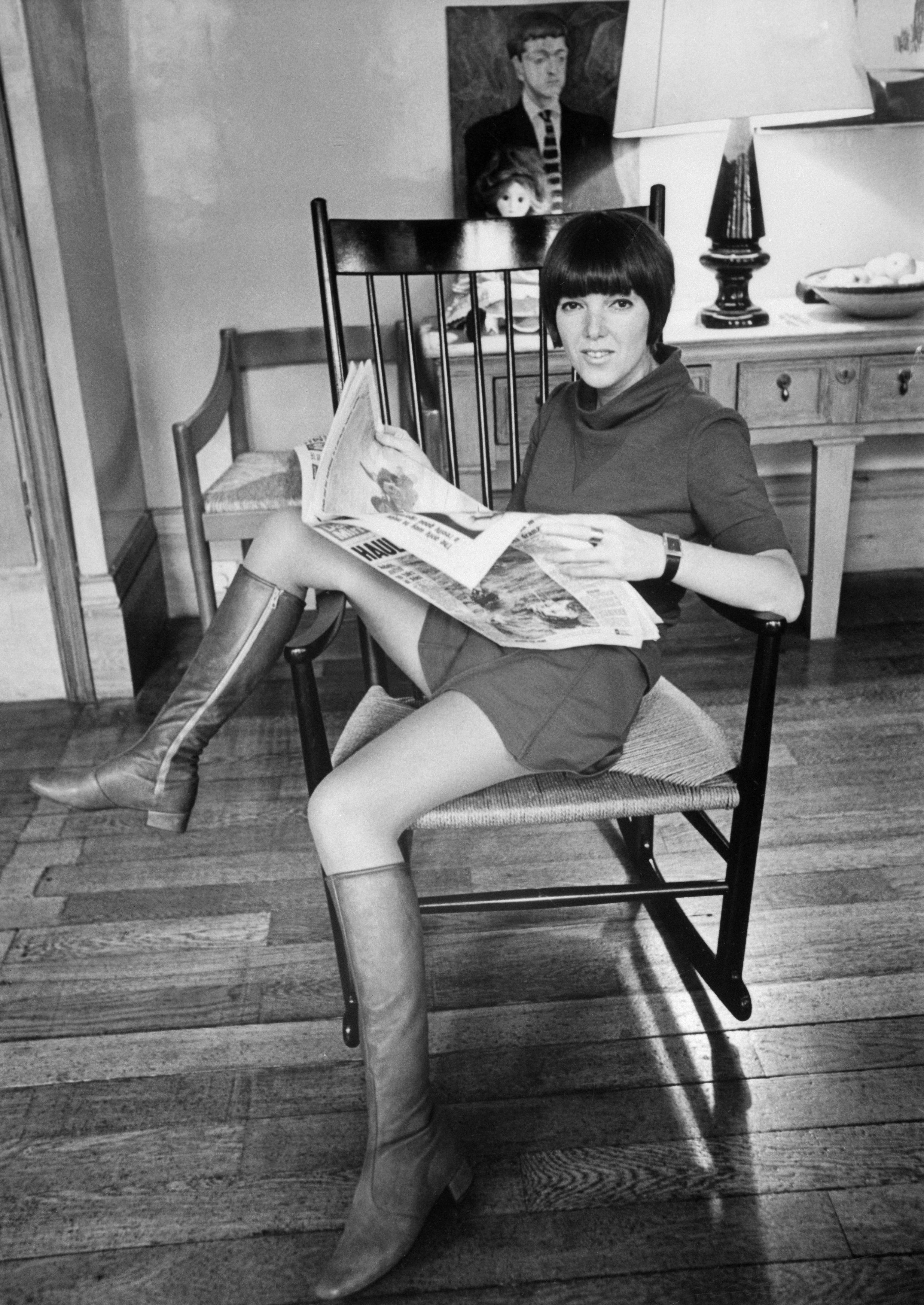

Mini but mighty: How Mary Quant raised hell (and hem) by inventing the mini skirt

The pioneering designer’s bold look caused a frenzy, not just in Britain but around the world

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.“Immoral! Disgusting!” So said those who were scandalised when Mary Quant’s mini skirts made their way onto the streets of London and beyond.

The British fashion designer, who has died aged 93, was widely credited with popularising the look and was one of the most influential figures in the fashion scene of the Sixties.

Born in south-east London on 11 February 1930, Quant was the daughter of two Welsh school teachers. She gained a diploma in the 1950s in Art Education at Goldsmith’s College, where she met her husband Alexander Plunket Greene, who later helped establish her brand.

Quant was taken on as an apprentice to a milliner before making her own clothes and in 1955 opened Bazaar, a boutique on the King’s Road in Chelsea.

“It’s impossible to overstate Quant’s contribution to fashion. She represented the joyful freedom of Sixties fashion, and provided a new role model for young women. Fashion today owes so much to her trailblazing vision,” the Victoria & Albert Museum said in its tribute.

In a piece discussing the emergence of the mini skirt, the V&A shows a version of a dress Quant designed for her Mary Quant Ginger Group label, which launched in 1963. It was owned by Sheffield-based Jenny Fenwick, who said: “Mary Quant epitomised a style which was different from the norm and meant that teenage girls like me didn’t have to look like their mothers.”

Her designs sparked a mass market-boom in mini skirts, with hemlines starting just above the knee but steadily creeping upwards. In 1967, she told The Guardian that her shorter dresses and skirts, made in loud colurs, were “arrogant, aggressive and sexy”.

Despite now being highly praised for liberating British women from restrictive and overly formal clothing, Quant’s designs were not accepted by everyone at the time.

Although they were all the rage in London, mini skirts were considered “mad” in other cities, even in Paris and New York. In 1966, Helen Lazareff, the former editor of Elle said that Parisians would not adopt the short hemlines because young French people were not “so restrained that [they] had to break out” of societal norms like the English.

Meanwhile, in Russia, the mini skirt was derided as a floozy distraction from “social revolution”. A writer who went with the byline Miss A Belskaya wrote that the mini skirt was linked to “the idea that young people should dance every night until they are dizzy, play at free love, smoke marijuana” and accused it of being a capitalist attack on socialism.

Closer to home, Quant recalled in her 1966 memoir Quant by Quant that men would protest against her clothing. “City gents in bowler hats beat on our shop windows with their umbrellas shouting, ‘Immoral!’ and ‘Disgusting!’ at the sight of our mini skirts over tights,” she wrote. “But customers poured in to buy.”

It was clear that despite all the ruckus, Quant’s creations were going nowhere. When Twiggy, the model of the era, began adopting her designs, their popularity reached stratospheric heights. Twiggy became synonymous with Quant’s collections and the pair would go on to collaborate closely throughout the years.

Model Jackie Bowyer also wore Quant’s designs and became particularly famous for a black-and-white photograph, in which she is swinging from a street lamp pole and wearing a black oilskin coat with a matching hat and boots by the designer. The outfit was shown at the first Sunday Times International Fashion Awards ceremony in 1963.

When asked which models and celebrities wore the mini skirt best, Quant told The Herald in 2018: “Jean Shrimpton, of course, was unbeatable, and also Audrey Hepburn... But there were many others... Twiggy, Sandra Paul, Grace Coddington.”

Quant was also very outspoken about her attitude towards sex and sexuality. According to V&A fashion curator Jenny Lister, she “would make provocative statements about sexuality and her private life as well, which perhaps went along with her clothes, which were seen as quite outrageous at the time”, as per the Fashion Network.

Her influence in fashion coincided with the emancipation of women in the Swinging Sixties, as the contraceptive pill became available just six years after Quant opened her legendary boutique on the King’s Road, Bazaar.

In the 2021 documentary Quant about her life, directed by Sadie Frost, Quant summarises her life’s work succinctly: “I think the point of fashion is not to get bored with looking at somebody, I think the point of clothes for women is that one, you’re noticed; two, that you look sexy; and three, that you feel good.”