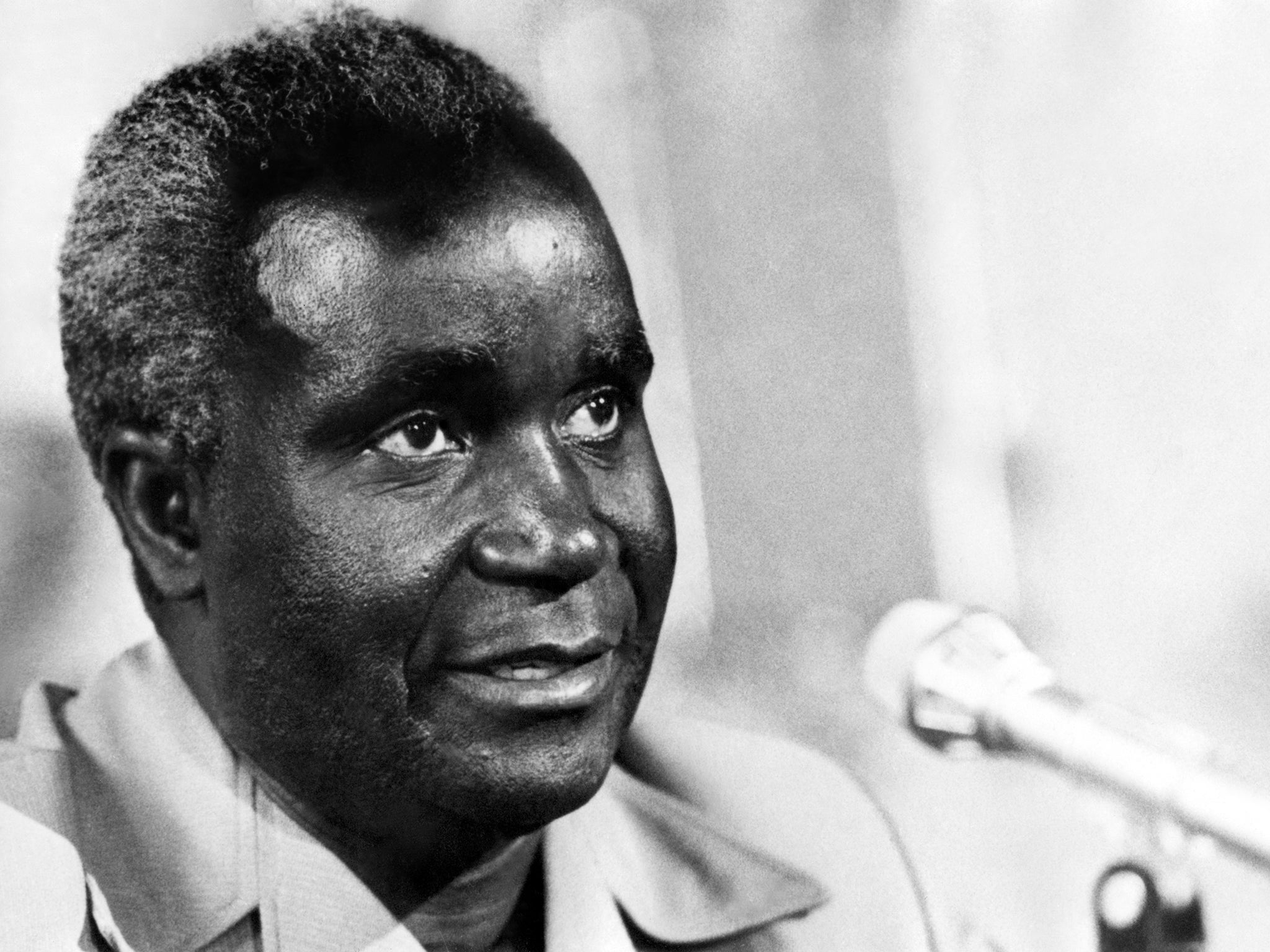

Kenneth Kaunda: President and founding father of Zambia

The politician fought for liberation and led the country to freedom from British rule

Kenneth Kaunda, a symbol of African liberation who led Zambia to freedom from British rule, has died aged 97. He served as the country’s first president and maintained a loose grip on the nation for 27 years.

Even after he left office in 1991 following a crushing election defeat, Kaunda was a revered figure for many Zambians who knew him as “KK”. He had campaigned for black liberation while crisscrossing the countryside in the 1950s and 1960s, then emerged as a leader of Africa’s first generation of post-colonial leaders while calling for an end to white-minority rule on the continent.

“People were fed up with him by the end, but now there’s a great deal of nostalgia for his leadership, particularly the way he was seen as a unifier,“ says Scott Taylor, the director of the African studies programme at Georgetown University. “A lot of the country today seems to be more divided, regionally or ethnically. People look back on Kaunda as living up to his slogan: ‘One Zambia, one nation.’”

As president, Kaunda led a patchwork country of more than 70 ethnic groups and 8 million people (the population has since more than doubled), maintaining stability even as conflict raged in neighbouring countries such as Angola and Zimbabwe. Delivering speeches about African comity and the challenges facing the continent, he sometimes wept into his white linen handkerchief, clutched in his left hand.

In part, Kaunda enforced Zambian unity by fostering a cult of personality, creating tens of thousands of civil service jobs and presiding over nearly two decades of one-party rule. Political opposition was outlawed, although he was never known for the brutality that characterised the regimes of leaders such as Mobutu Sese Seko of Zaire (now known as Congo) or Hastings Banda of Malawi. “It wasn't the iron-fist approach that others took,” Taylor says. “He never went to extremes of violence or tribalism.”

Kaunda, a teetotalling former schoolteacher and avid ballroom dancer, espoused what he called a humanist political philosophy, which mixed socialism with soaring rhetoric about the importance of community. His government nationalised the copper mines that fuelled Zambia’s economy, sought to expand manufacturing and agriculture, and subsidised healthcare, education and the cost of food. Yet when copper prices fell in the early 1970s, the economy collapsed, leading Kaunda's administration to borrow more than $6bn (£4.3bn) from foreign governments and financial institutions.

As copper prices continued to plunge, Kaunda struggled to tame rampant inflation. The country faced chronic shortages, with people sometimes lining up for hours to buy corn, soap or milk. In 1990, he faced growing criticism after a World Bank programme forced him to raise the price of cornmeal, a staple food, prompting riots in which dozens were killed. Kaunda endured an abortive military coup before agreeing to legalise opposition parties and schedule multiparty elections, which were monitored by western observers including former president Jimmy Carter.

By then, he had acquired a reputation as a respected if somewhat eccentric statesman. He chaired the Organisation of African Unity, backed efforts to end apartheid in South Africa and welcomed members of the banned African National Congress to Lusaka, which emerged as a base for nationalist leaders from across the region. He also cultivated close ties with the west, granting frequent interviews with journalists and courting diplomats by inviting them to play golf on a private course around his State House mansion.

“He, more than anyone else, has been responsible for the principle of nonracialism in African politics,” Richard Sklar, a professor emeritus of political science at UCLA, told The Boston Globe in 2002. “On that he stands with Mandela.”

Kaunda was also known for backing quixotic economic development projects, including what The Philadelphia Inquirer described as “an agrarian utopia” he wanted to build with the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi. His United National Independence Party was accused of corruption, although charges seldom stuck to Kaunda. “There is almost no money to maintain roads, hospitals or schools,” The Washington Post reported in 1988. “Mass transport hardly exists.”

With urban discontent on the rise and pro-democracy movements budding across Africa, Kaunda was swept out of office in the 1991 presidential election, winning only about 25 per cent of the vote. He lost to Frederick Chiluba, a trade union leader whom Kaunda’s regime had jailed years earlier.

After the votes were counted, Kaunda appeared on national television to congratulate his opponent and accept the results. “The true lesson of democracy is to accept the verdict of the people,” he said. “This I will do … I have done my best for Zambia. This is the nature of multiparty politics. You win some, you lose some. It’s not the end of the world.”

Kenneth David Kaunda was born in the Zambian town of Chinsali, then part of Northern Rhodesia, in April 1924. Both his parents were schoolteachers – his father was also a Presbyterian preacher from Nyasaland, now Malawi – and Kaunda followed them into the profession before moving near the copper mines, where he founded a welfare office and farmers’ cooperative.

By the late 1940s, he was increasingly involved in the black liberation movement and helped organise a political group, the Zambian African National Congress. His independence activities landed him in prison for several months. After being released in 1960, he formed a new party, the Unip, and renewed his campaign of civil disobedience, modelled after Mahatma Gandhi’s independence effort in India.

Kaunda served in Northern Rhodesia’s legislature and became prime minister in 1964, shortly before the protectorate gained full independence from Britain. He consolidated power in 1972, banning other political parties in what he described as an effort to keep order. “Every election, there is peace,” he said.

After leaving office, Kaunda appeared poised to run for president in 1996. But his successor, Chiluba, blocked his candidacy in the courts, and in 1997 he was wounded while travelling to a political rally, struck by a gunman’s bullet that grazed his forehead. Kaunda, who said he had information that Chiluba’s government was trying to assassinate him, was later accused of participating in an attempted coup. The charges were dropped, but he was briefly stripped of his citizenship.

His wife of more than six decades, the former Betty Banda, died in 2012. Kaunda disclosed in 1987 that one of his sons had died of Aids, a taboo subject across much of the continent, and later started a foundation to combat the disease. Another son, a rising politician named Wezi Kaunda, was shot and killed by four gunmen in 1999, in what Kaunda’s security chief said was an assassination. Authorities said they thought the attack was an attempted carjacking.

Information on survivors was not immediately available.

Defending his record as president, Kaunda often cited Zambian stability as his greatest achievement. “Peace, unity, love. One Zambia, one nation. That is what I believe and that is what we have,” he said in 1991, during a campaign stop in the village of Chongwe. “Look around Africa, what do you see? Starvation. War. Chaos. Look at our poor brothers in Zaire, Angola, Mozambique, Ethiopia, Uganda. Zambia is at peace, not in pieces.”

Kenneth Kaunda, president and political leader, born 28 April 1924, died 17 June 2021

© The Washington Post