Kofi Annan: Former UN secretary general and Nobel Peace Prize laureate

The Ghanaian national was the first and only black African to be appointed as the world’s top diplomat, a tenure that saw him mediate in some of the biggest crises of the 21st century

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In December 1996, the selection of Kofi Annan as the seventh secretary general of the United Nations had been a milestone. This was the first time in the history of the UN that a secretary general had been chosen from the UN staff, and Annan, an international civil servant, had come up through the ranks in management and personnel departments.

There were immediate comparisons made between Annan and the third secretary general, Dag Hammarskjold. Hammarskjold had also been welcomed as a quiet and ghanaunassuming bureaucrat but had gone on to transform the office of secretary general from one of an international administrator to that of a world statesman and had become a world figure.

Annan began his professional life as an administrator and aged 24 had joined the international civil service as a budget and administrative officer for the World Health Organisation (WHO). Ten years later he was awarded a management degree from Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

When Hammarskjold had taken the helm in 1953, appointed from the Swedish civil service, he had been horrified at the magnitude of his task. Annan in contrast was already well acquainted with the UN’s constant crisis management, its inherent weaknesses, its institutional complexity, and its serious and damaging lack of coordination between its organisations and programmes.

The comparisons between Hammarskjold and Annan were inevitable and when Annan assumed office in January 1997 there were high hopes for what he might achieve. Almost everyone has a different idea about what the job of secretary general is but for Annan a more central and more immediate predicament existed. He had not been everyone’s choice.

Many UN member states had wanted his predecessor to remain for a second term, the outspoken Dr Boutros Boutros-Ghali, an Egyptian diplomat and politician. But in a sorry and a shameful spectacle Boutros-Ghali had been drummed out of office by the Clinton administration. The Americans lobbied hard for Annan to take his place, diplomats from the US mission to the UN arguing that Annan was the only UN official in which they had any confidence.

The Americans promised Annan that once he was in office the debt the US owed to the UN would be paid. In December 1996, The New York Times had described Annan’s selection as another key appointment for President Clinton’s second term, as though the UN were a division of the US government.

Kofi Annan was born on 8 April 1938 in a small town called Bekwai, near Kumasi, Ghana. His father was the elected governor of Ashanti province and a hereditary paramount chief of the Fante people. At the time Ghana was a British colony and called the Gold Coast, and his father worked for a subsidiary of Unilever dealing in cocoa exports and various imports.

Annan went to Ghana’s leading boarding school and later enrolled in the University of Science and Technology at Kumasi, a provincial capital. He completed his undergraduate work in economics at Macalester College, St Paul, Minnesota, in 1961 with the help of a grant from the Ford Foundation. From Minnesota he went to Geneva to the Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies and then, as a 1971-72 Sloan Fellow, he studied at MIT and received a master of science degree in management.

His first job within the UN system was as a lowly administrative and budget officer with the WHO, where he appeared efficient, tactful and persuasive – but Annan wanted to work in Africa and he resigned from the WHO and found a job as head of the personnel section at the Economic Commission for Africa in Addis Ababa.

Annan was ambitious and from Addis Ababa he decided to go to America to study management, at MIT, after which, in the mid-Seventies, he went home to Ghana to run the Ghana Tourist Development Company. But here he felt restricted. Ghana was under military rule. Annan returned to the UN system and he went to Geneva to the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees. It was a crucial period with a dramatic increase of refugees worldwide, a result of events triggered by the fall of Saigon that saw nearly 2 million Indo-Chinese flee Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos.

In the mid-Eighties Annan was promoted. He moved to New York where he served as assistant secretary general for programme planning, budget and finance and was appointed controller in that office in 1990. That year, following the invasion of Kuwait by Iraq, Annan was asked by the then secretary general, the Peruvian Javier Perez de Cuellar, as a special assignment, to facilitate the repatriation of more than 900 international staff and the release of western hostages in Iraq.

Annan negotiated with Iraq the safe passage of 500,000 Asian workers stranded in the region. It was Annan who led the first UN team negotiating with Iraq on the sales of oil to fund purchases of humanitarian aid. And so Annan managed to make a difficult transition from finance and management to international diplomacy. And as it happened, at that very time, and as a result of the end of the Cold War, there was an expansion in UN peacekeeping.

Annan was appointed assistant secretary general for peacekeeping operations on 1 March 1993, just as the tragic UN peacekeeping mission in Somalia was experiencing real difficulties: that summer 23 peacekeepers from Pakistan lost their lives and in October 18 soldiers from the US elite forces were killed by Somali militiamen. Later on, Annan would be critical of the speed with which the US withdrew its troops from Somalia after the deaths of the soldiers. He said that the impression had been created that the easiest way to disrupt a UN mission was to kill Americans.

In February 1994 Annan was appointed under secretary general for peacekeeping, a post he held until he was selected secretary general. Between November 1995 and March 1996, following the Dayton Peace Agreement that ended the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Annan served as special representative of the secretary general to the former Yugoslavia, overseeing the transition in Bosnia and Herzegovina from the United Nations Protection Force to the multinational Implementation Force, led by NATO.

It was at this moment that he came to the attention of American diplomats and they would report how efficient this UN civil servant and how calm and collected. Annan was never inoffensive and he was elegant and well mannered. He was diligent and patient. He had a British accent.

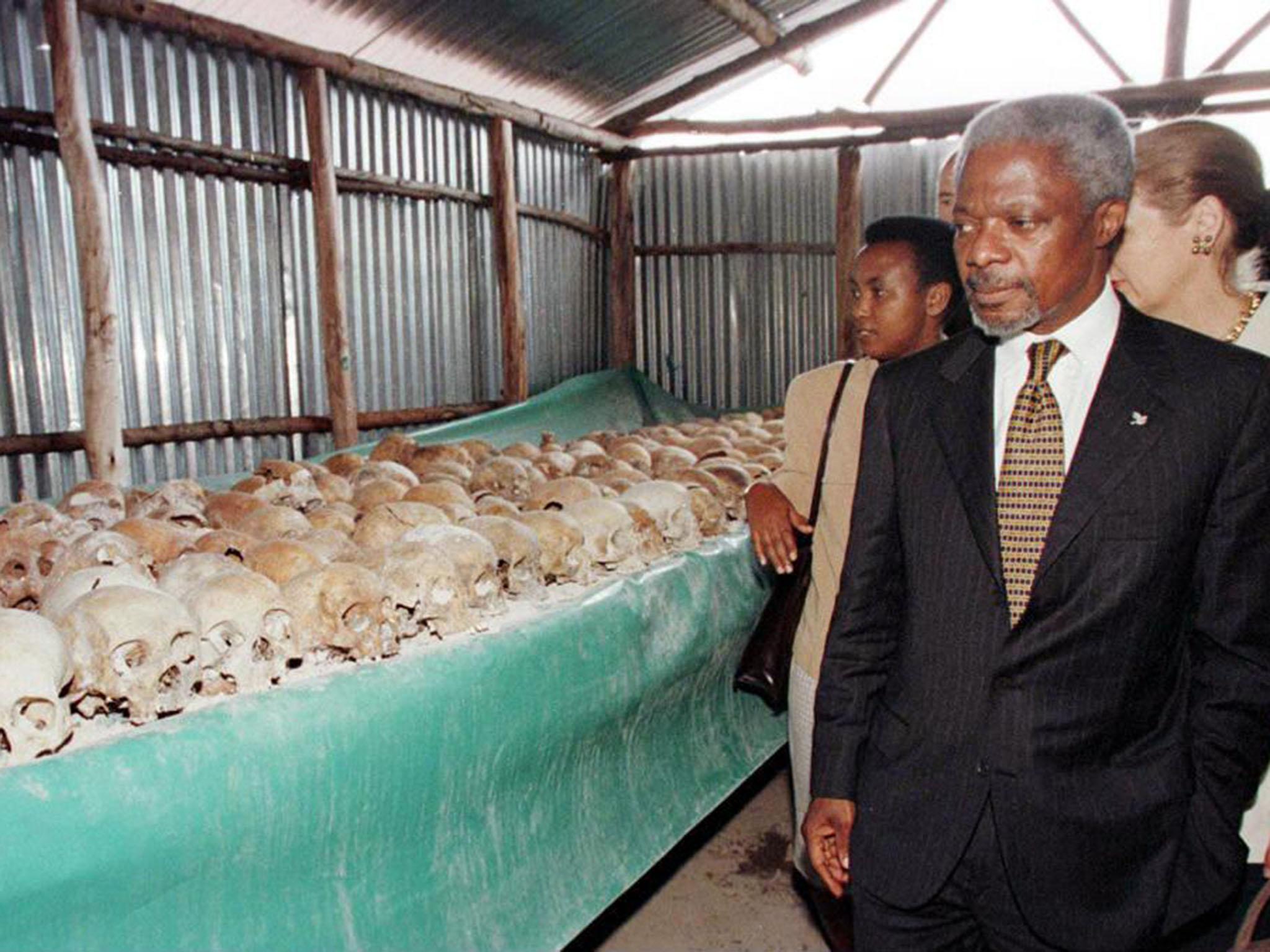

During Annan’s term as head of peacekeeping there was an unprecedented growth in the size and scope of UN peacekeeping, with a total deployment at its peak in 1995 of almost 70,000 military and civilian personnel from 77 countries. It was also a time of the UN’s greatest humiliations and the genocide in Rwanda would define the consequences of inaction. Two particular episodes would come to haunt Annan, the genocide in Rwanda that took place between April and July 1994 and the massacre in Srebrenica in July 1995

When Kofi Annan’s term as secretary general began in January 1997 his first major initiative was to propose a plan for reform, presented in a document, “Renewing the United Nations”, which was given to UN member states in July and was pursued with an emphasis on improving coherence and coordination. A cabinet of the UN’s most senior officials was established, breaking the tradition whereby each official briefed the secretary general individually. In this way Annan hoped to address the UN’s organisational incoherence.

To ease a ridiculous workload Annan was successful in seeking approval from the General Assembly for the appointment of a deputy secretary general. Of note in these early years, in April 1998, was his report to the Security Council on “The Causes of Conflict and the Promotion of Durable Peace and Sustainable Development in Africa”. He was keen to increase the international community’s commitment to Africa.

Annan quickly proved himself a consummate diplomat and he used his good offices in several key political crises, including an attempt in 1998 to gain Iraq’s compliance with Security Council resolutions. His ability in this case to pursue a sensible diplomatic path while US forces were amassing in the Gulf was lauded in the American press and there were favourable profiles. He was credited with having prevented the bombing of Iraq. In 1998 Annan helped to promote the transition to civilian rule in Nigeria and in 1999 he mediated an agreement to resolve a stalemate between Libya and the Security Council over the 1988 bombing of a jet airliner over Lockerbie.

Annan’s quiet diplomacy in 1999 helped to forge an international response to violence in East Timor. In the latter case he negotiated with the Indonesian government in Jakarta to let UN peacekeepers into the country. He was a skilful moderator in the Middle East in October 2000 and amid a serious escalation in violence and with many Palestinians shot dead by Israeli troops he was said to have been instrumental in persuading Yasser Arafat to travel to an international conference at Sharm el Sheikh.

Throughout this period Annan was dogged by questions from the past into his role as head of UN peacekeeping between 1993-1994, in the circumstances of the tragedies of Rwanda and Srebrenica. In Srebrenica in July 1995 a massacre of the Muslim population had taken place after the town had fallen to besieging Serb forces. There was TV news film of the men and boys led away to be killed and Danish peacekeepers nearby had been vilified for their inactivity. The tragedies in Rwanda and in Bosnia had exposed the role played by UN officials before now of little concern to the media.

Annan set up two internal inquiries, one into each tragedy. This resulted in reports in which blame was evenly spread and although the reports heralded a break with UN tradition, they were notable for their lack of specific information although they did go some way to expose the decision-making in the Security Council – always in secret and informal sessions – and an international civil service whose officials seemed incapable of adequately managing UN missions. Some human rights activists remain convinced that all involved in these two events should have resigned. The spotlight remained on Annan. Less attention was paid to the role of his predecessor, Boutros-Ghali, whose behaviour at this time was never fully explained.

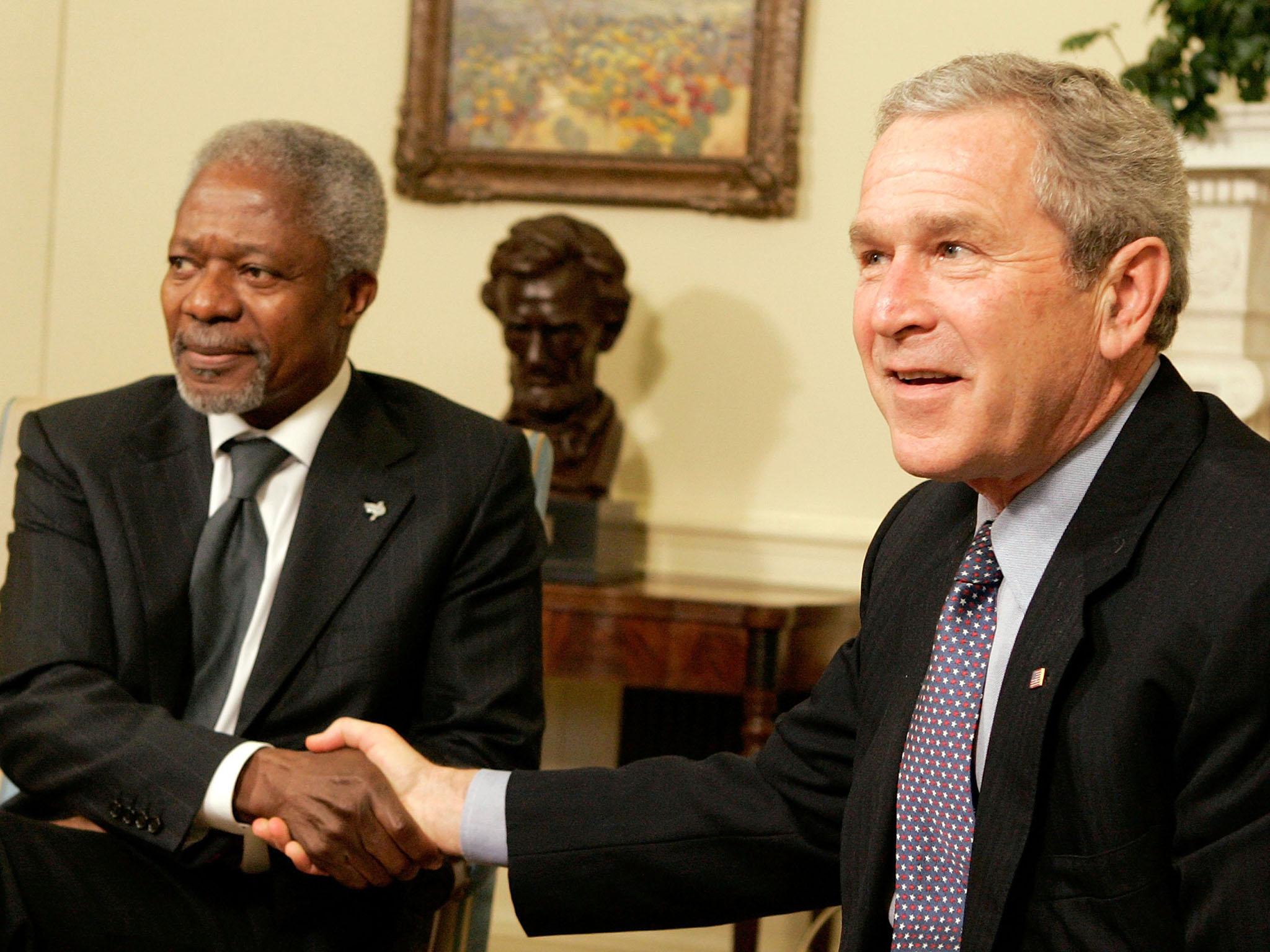

Whatever the lessons of these disastrous years there remained a gulf between what was needed in UN peacekeeping and the means provided by member states. Nor did the Security Council change its ways, the five permanent members failing as usual to provide adequate and timely intelligence information to UN missions in the field. What was really needed was a peacekeeping revolution within the UN and within the defence ministries of its most powerful nations. And this was unlikely with a Republican president, George W Bush.

One of Annan’s most notable achievements was to sell the UN to sceptics. Annan, a man who chose his words with great care, often managed to side-step Washington and brought the UN closer to the people. He actively courted Hollywood; film star Michael Douglas was appointed a special UN ambassador. CNN founder Ted Turner gave a massive donation for UN programmes. Annan tried to promote an idealistic moral world view and seemed determined that the mistakes of the past, and particularly the immediate past, would never be repeated.

He gave the organisation a more streamlined image and he was admired and respected by those who worked for him. He was a quiet man, a calming presence and unflappable. While others pointed out that a more realistic approach for UN success would entail warships, combat aircraft and war fighting troops, he remained hopeful and quietly determined. To have completely altered the nature of UN peace forces would entail changing the institution itself beyond recognition. A safer option for reform was chosen.

There were problems and serious challenges to the institution during his term of office. Annan had strong reservations about Nato’s 1999 unilateral intervention in Kosovo, the bombing used to try to prevent human rights abuses. In his annual report for 1999 he cautioned those who welcomed Nato’s campaign to remember that actions without Security Council authorisation threatened the very core of the international security system founded and based on the UN Charter, although he did believe that borders should not prevent intervention and that sovereignty was not a shield for human rights abuses.

For Annan a new international solidarity in favour of intervention represented a humanity that cared more, not less, for the world’s suffering. A developing international norm in support of intervention was for Annan a hopeful sign at the end of the 20th century but it was imperative that the UN be central to it.

Annan knew better than any other secretary general before him how the UN system worked. Most importantly, he was aware of the low morale of the UN staff. This was a toxic bureaucracy in which promotion depended on nationality rather than ability and Annan made sure that reform of the UN bureaucracy was a permanent item on the agenda, but efforts were hampered by the continuing debt crisis with the amount that America owed reaching well over $1bn (£7.8m).

By 2000 the new trend was for the UN to enter into partnership with corporations. There were many critics of this policy but Annan believed that the UN’s original aims would not be subverted, and the private sector would be eager to provide funds. He was outspoken at the 2001 World Economic Forum at Davos when he warned against a background of protest, that world business leaders faced a backlash against their globalisation unless their companies became better world citizens.

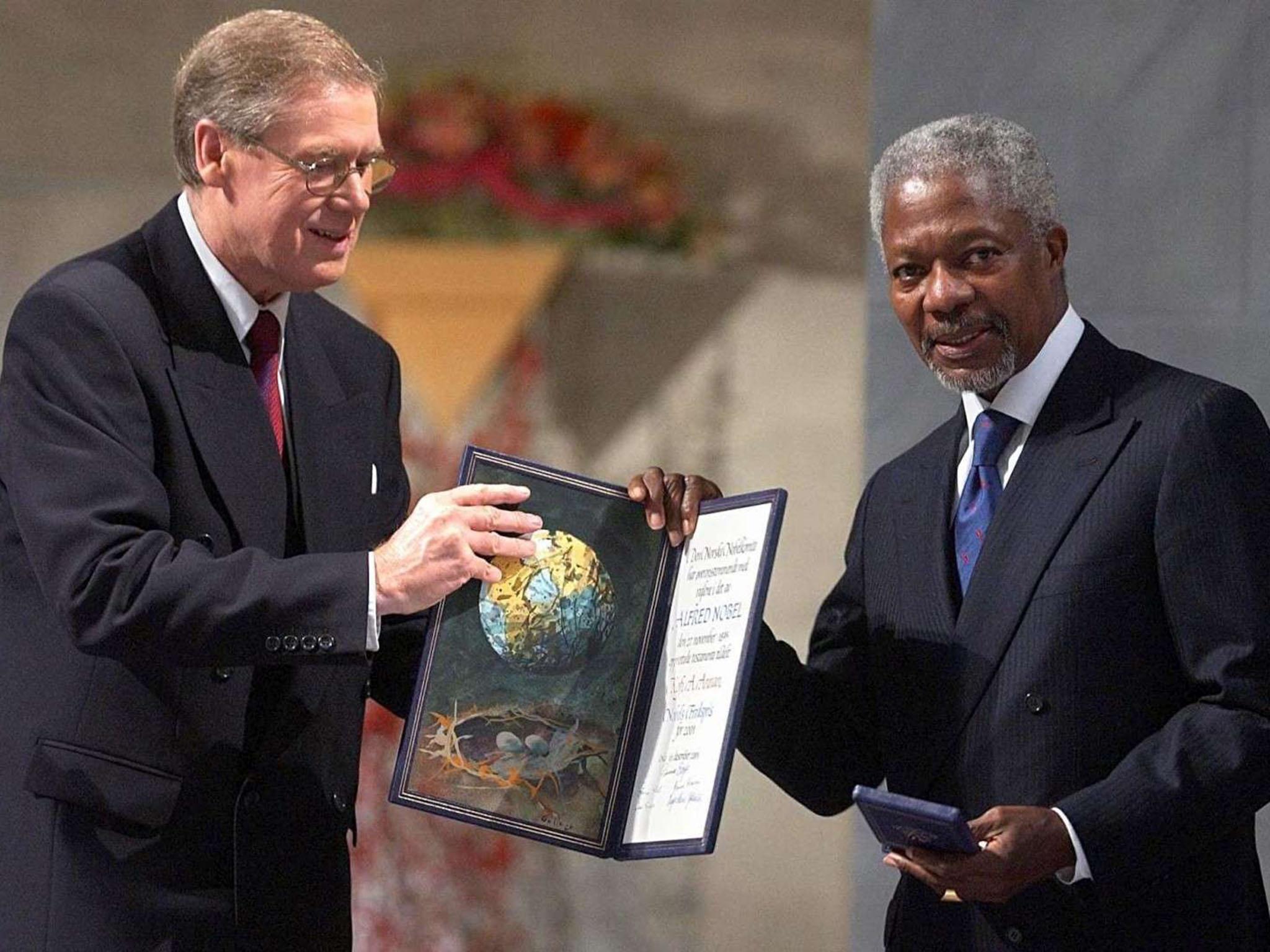

The same year, Annan and the UN were jointly awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for their efforts to “revitalise” the UN and for “having given priority to human rights”. Annan was also recognised for his commitment to the fight against the spread of HIV in Africa and his outspoken opposition to international terrorism.

In 2003, the US announced its intention to bypass the UN and invade Iraq, despite Annan urging them and the UK not to intervene without the UN’s support. In a September 2004 interview, Annan told the BBC: “From our point of view and from the charter point of view, it was illegal.” This drove a wedge between Annan and the US, one of his biggest supporters, and caused him problems when he was implicated, both professionally and personally, in the “oil for food scandal” in 2004.

Reports surfaced that Annan’s son Kojo had received payments from the company monitoring the programme, which was started in 1996 to sell limited quantities of oil from sanction-hit Iraq in return for humanitarian supplies. Annan called for an investigation which cleared him of using improper influence a year later, but did identify failings in how he had overseen the programme. In the US, politicians called for his resignation.

However, it wasn’t until 2006, after 10 years at the helm and nearing 70, that Annan stepped down as secretary general of the UN. In his final speech, he called on the US to return to President Truman’s multilateralist foreign policies, saying “the responsibility of the great states is to serve and not dominate the peoples of the world”. He also said the US must maintain its commitment to human rights “including in the struggle against terrorism”.

During much of his time in office his wife, Nane Marie, often travelled with him and she was seen as a tremendous asset. He had married her, a Swedish jurist and painter, in 1984. It was a second marriage for both. His son, Kojo, and daughter, Ama, are from his first marriage.

Nane is a niece of Raoul Wallenberg, the Swedish diplomat who saved thousands from death at the hands of the Nazis. The couple were often described as near perfect and Annan paid tribute to the help that Nane brought him during his years as secretary general.

Despite his resignation, Annan continued to fight for diplomacy and human rights. In 2007, he set up the Kofi Annan Foundation, which works “towards a fairer, more peaceful world”. A year later, he helped broker an arduous power-sharing agreement between Kenyan opposition leader Raila Odinga and former president Mwai Kibaki, putting an end to the post-election violence which left at least 1,000 people dead, and 300,000 displaced.

In February 2012, he was appointed by the UN and Arab League as joint special representative for Syria in an attempt to end the civil war, a post he resigned from in August of the same year, saying the peace mission was impossible because of militarisation on the ground and lack of international unity.

The following year, he was appointed as the chair of the Elders, an independent group of world working together for peace and human rights and brought together by Nelson Mandela. In 2016, Annan was appointed to lead a UN commission to investigate the Rohingya crisis.

“I’ve discovered retirement is hard work,” he said in an interview with the BBC to mark his 80th birthday.

Kofi Annan, UN secretary general, born 8 April 1938, died 18 August 2018

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments