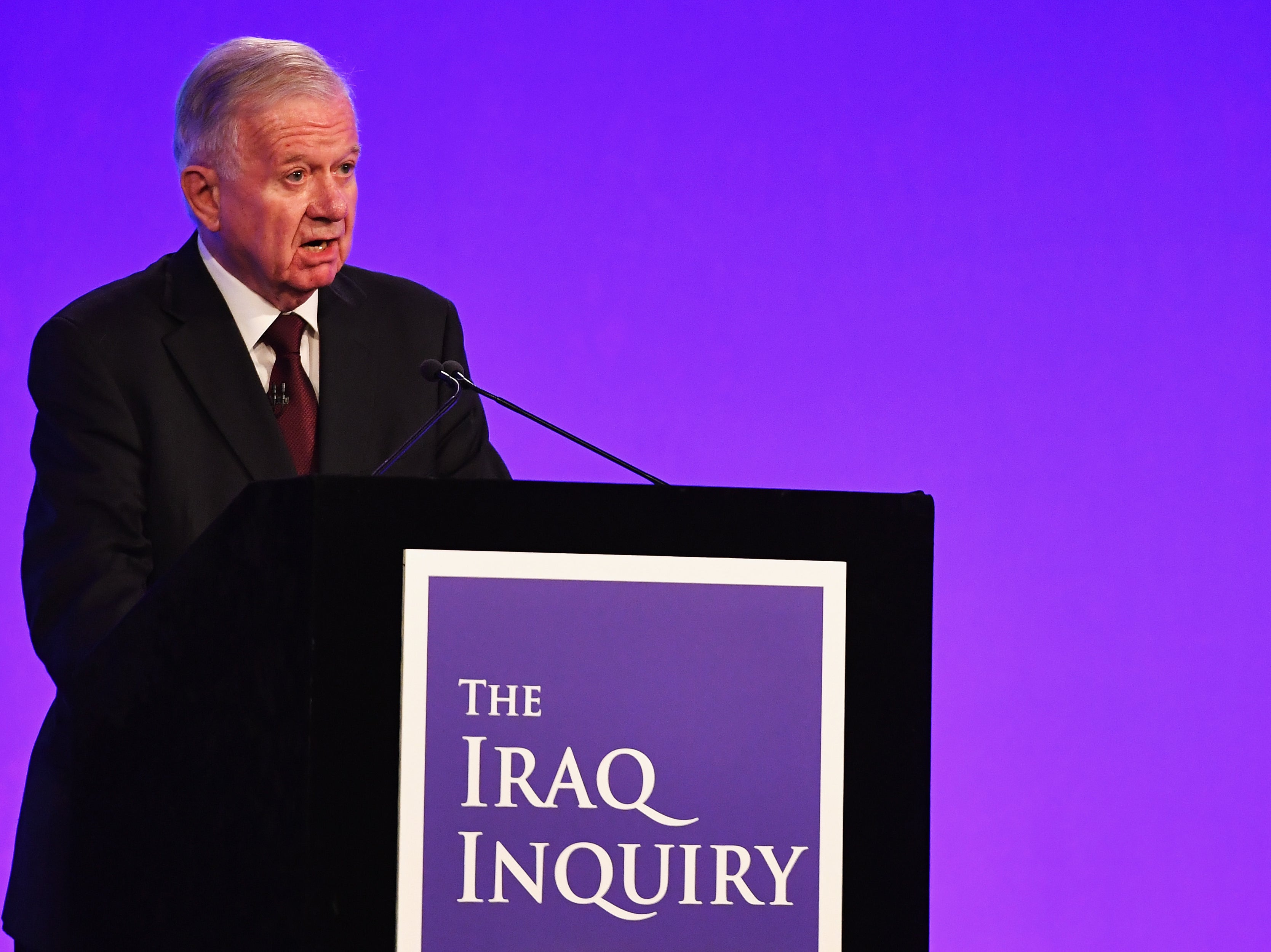

John Chilcot: Devoted civil servant who led damning inquiry into Iraq war

Chilcot’s 2.6-million-word report forensically stripped bare the campaign’s deceit and its failures, as well as delivering a withering verdict on Tony Blair

At home in the wilds of Dartmoor one Friday evening in June 2009, the retired civil servant, Sir John Chilcot, who has died aged 82, received a phone call from the cabinet secretary inviting him to chair the forthcoming inquiry into the 2003 invasion of Iraq. At least 150,000 Iraqi citizens were killed during the war that followed the invasion, along with 179 British military personnel.

While Chilcot was viewed as a safe pair of hands, the confirmation of his appointment by prime minister Gordon Brown on the Monday morning was met with widespread public unease about what he could actually achieve. Part of that scepticism stemmed from discontent with two recent public inquiries – the Hutton Inquiry into the death of weapons inspector Dr David Kelly, and the Butler Review, in which Chilcot was involved, which looked into the failings in intelligence in respect of Iraq’s alleged weapons of mass destruction. Describing Tony Blair’s administration as “sofa government” was perhaps the most severe of Lord Butler’s criticisms.

Chilcot displayed a tenacity that was belied by his outwardly mild-mannered approach to life. He served for seven years as permanent under-secretary of state at the Northern Ireland Office, during which time he witnessed the many difficulties endured by Lord Saville in relation to his inquiry into Bloody Sunday. Chilcot immediately displayed his independence by rejecting Gordon Brown’s initial demands for evidence to be given under oath and in secret. Instead it was decided that, whenever possible, witnesses would be heard in public.

The panel began their work during the autumn of 2009, and called their first witness in November that year; the last, former foreign secretary Jack Straw, was called almost two years later, in February 2011. Within his broad terms of reference, Chilcot considered Britain’s involvement in Iraq between 2001 and 2009, taking in the run-up to the conflict, the invasion itself, and its aftermath. Among the 100 witnesses were Alastair Campbell – Blair’s former head of communications – and Gordon Brown. There were also two extraordinarily tense sessions with Blair.

Considerable delays followed, due in part to “Maxwellisation”, the requirement that people who were criticised in the report be given the right to reply before publication. Not helping was Chilcot’s own resolve to view all relevant documents, particularly the notes between Blair and George W Bush.

When it was finally published, to wide praise, in 2016, the 12-volume, 2.6-million-word report, plus 145 pages of summary, was three times as long as the Bible. In it, Chilcot forensically stripped bare the campaign’s deceit and its failures. He found that Britain had chosen to join the invasion of Iraq before all peaceful options for disarmament had been explored. Policy was constructed on the basis of intelligence that had gone unchallenged, while the legal basis for military action was spurious at best and undermined the authority of the UN Security Council.

In addition, the military gravely underestimated its abilities, finding itself in circumstances in southern Iraq that Chilcot described as “humiliating”. Chilcot also strongly reiterated the point that never again should there be unchallenged obedience to any leader. As if to emphasise this, he quotes from a note sent by Blair to Bush in July 2002, which states: “I will be with you, whatever.”

The only son of artist Henry Chilcot and his wife, Catherine, born just before the onset of the Second World War, John Anthony Chilcot won a scholarship to Brighton College in 1952. Five years later he moved to Pembroke College, Cambridge, as an exhibitioner, initially reading English before switching to modern and medieval languages.

After graduating in 1960, he stayed on to work for a PhD, but never got round to completing his studies. Instead, he joined the civil service in 1963, spending a significant portion of his early career at the Home Office. Three years later he became an assistant private secretary to the home secretary, Roy Jenkins, later serving as a principal private secretary to home secretaries Merlyn Rees and William Whitelaw. Between 1971 and 1973 he was private secretary to the head of the civil service, Sir William Armstrong, before working in the Cabinet Office. From 1980 until 1984, he took on the challenging role of director of personnel and finance at the Prison Department just as numerous riots were breaking out throughout the sector.

In his own typically understated way, his ability to remain resolute in the face of intense pressure was much in evidence following his move to the Northern Ireland Office in 1990. Over the next seven years he would come to play an increasingly pivotal role in helping hasten the province’s transition to peace. Three years on he found himself in a Los Angeles courtroom defending claims that an escapee from the Maze Prison, James Smyth, would be in danger if extradited back to Ireland.

On his return to Belfast, a message purporting to come from Martin McGuinness, vice-president of Sinn Fein, was passed to him by an MI5 contact. It read: “The conflict is over but we need your advice on how to bring it to an end.” Eventually deciding that it was genuine, Chilcot quietly opened up channels of communication as the first tentative steps to what ultimately became the 1998 Good Friday Agreement began to take shape.

Although he was supposedly retired, over the coming years Chilcot’s talents were more in demand than ever. He served on the commission set up by Blair under his old boss, now Lord Jenkins, to review the voting system. From 1999 until 2004 he was staff counsellor to the security services, acting as an agony aunt to the 8,000 staff in MI5, MI6 and GCHQ. While chairman of the Police Foundation, he also took charge of a root and branch review into Royal and VIP protection. When chairing the not-for-profit Building and Civil Engineering Group, he attempted to provide a cheap pension scheme to millions of British workers. From 2007 until 2009, he chaired the committee looking at the highly sensitive issue of intercept evidence being used in criminal cases.

He was appointed CB in 1990, KCB in 1994, GCB in 1998, and a privy counsellor in 2004.

His wife Rosalind Forster, whom he married in 1964, survives him.

Sir John Chilcot GCB PC, civil servant, born 22 April 1939, died 3 October 2021