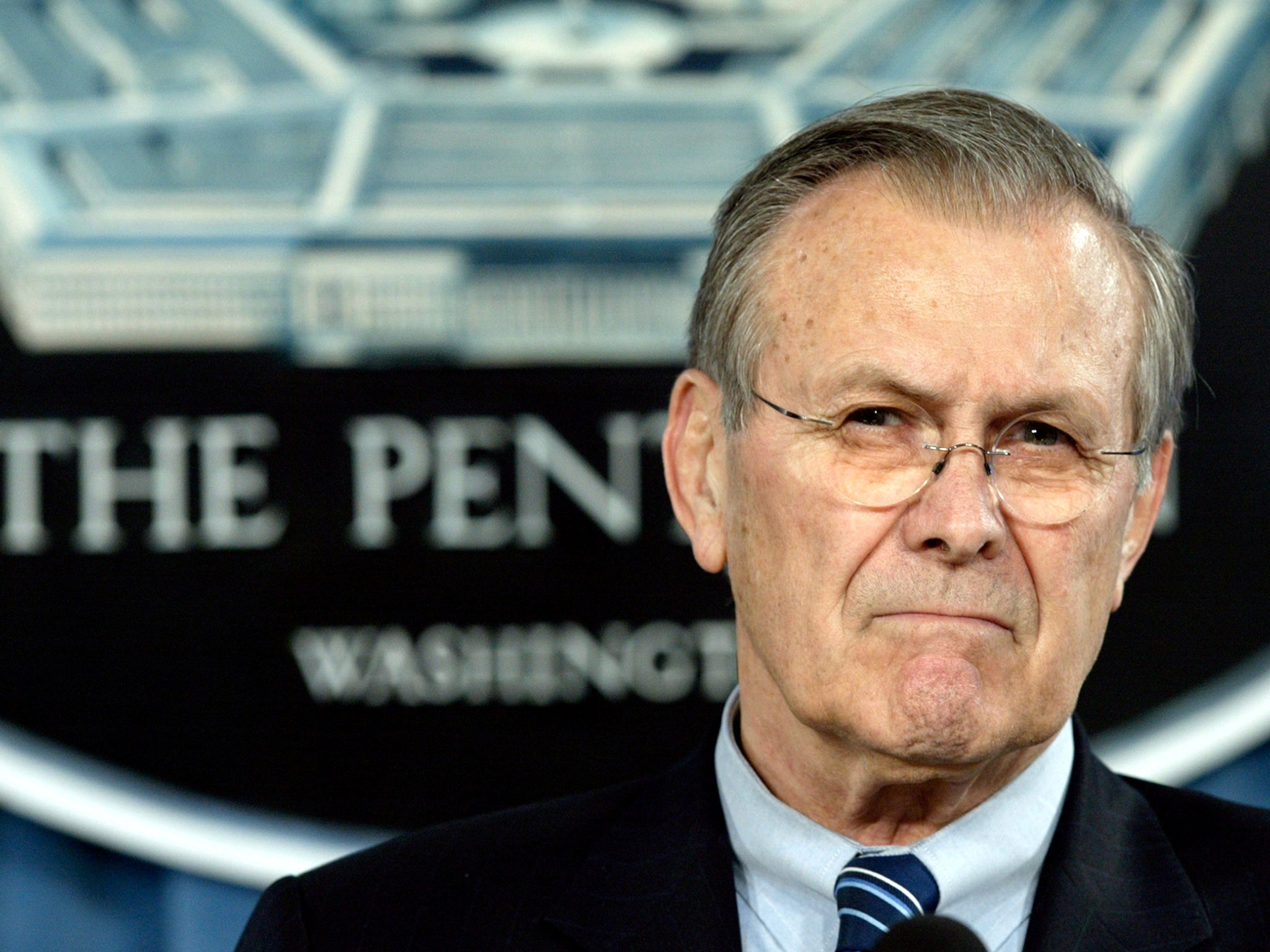

Donald Rumsfeld: Defence secretary who led the US into the Iraq War

Although Rumsfeld helped changed the face of US politics, his handling of the 2003 invasion eventually led to his downfall

Donald Rumsfeld, whose role overseeing the US invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq and his efforts to transform the US military made him one of history’s most consequential as well as controversial Pentagon leaders, has died aged 88.

Rumsfeld’s political prominence stretched back to the 1960s and included stints as a rebellious young Republican congressman, favoured counsellor to president Richard Nixon, right-hand man to president Gerald Ford and Middle East envoy for president Ronald Reagan. He also scored big in business, helping to pioneer such products as NutraSweet and HD television and earning millions of dollars salvaging large troubled firms.

His greatest notoriety came during a six-year reign as defence secretary under president George W Bush. Rumsfeld was initially hailed for leading the US military to war in the wake of the 9/11 terrorist attacks, but his handling of the Iraq War eventually led to his downfall. In the invasion’s aftermath, he was criticised for being slow to draft an effective strategy for countering an Iraqi insurgency. He also failed to set a clear policy for the treatment of prisoners.

Dogged for months by mounting calls for Rumsfeld’s removal, Bush finally let him go in late 2006. Rumsfeld's forced exit under clouds of blame and disapproval cast a shadow over his previously illustrious career.

Nevertheless, in a statement on Wednesday, Bush praised Rumsfeld as “a man of intelligence, integrity, and almost inexhaustible energy” who “never paled before tough decisions, and never flinched from responsibility”.

At the Pentagon, Rumsfeld ruled with a strong hand, persistently challenging subordinates, poring over details of troop deployments and insisting on a greater role in the selection of top officers than his predecessors had exercised. While capable of great charm and generosity, he often seemed to undercut himself with a confrontational, gruff and belittling manner that many found offensive. Senior officers complained that he treated them harshly, legislators groused that he was either unresponsive to their requests or disrespectful in personal dealings, and senior officials at the State Department and the White House portrayed him as uncompromising, evasive and obstructive.

“He wielded a courageous and sceptical intellect,” Douglas Feith, Rumsfeld’s senior civilian policy adviser at the Pentagon, wrote in a memoir. “But his style of leadership did not always serve his own purposes: He bruised people and made personal enemies, who were eager to strike back at him and try to discredit his work.”

When Rumsfeld took over at the Pentagon in 2001, Bush charged him with reforming the military bureaucracy to create more agile, adaptable armed forces. He proclaimed “transformation” as his main slogan and made a point of challenging traditional assumptions, insisting on the need for new principles of warfare and new weaponry to confront terrorism and other emerging threats.

At first, the invasion of Afghanistan in October 2001 appeared to validate Rumsfeld’s vision. The invasion also transformed Rumsfeld into a popular national figure. He had gotten off to a rocky start as defence secretary by alienating a number of officers, lawmakers and administration colleagues. But thrust into the role of war leader, Rumsfeld suddenly seemed made to order for the part.

After the Afghan invasion, Rumsfeld hoped to devise a similarly innovative war plan for toppling Saddam Hussein’s regime in Iraq. He expected US troops to stay in Iraq for only a short time, expecting to hand over responsibility for governing the country to an interim Iraqi authority.

A number of his key assumptions and early judgments proved wrong, and by the end of the war the US military death toll was 4,400, and 134,000 Iraqi civilians are estimated to have died.

He played down the scale and significance of widespread looting that immediately followed the invasion. During the first year of occupation, he left command of US troops in Iraq in the hands of an ill-prepared group led by the army’s newest three-star general. And he went along with a rushed move to disband the Iraqi military and build a new set of Iraqi security forces from scratch.

Moreover, Rumsfeld took issue with warnings that the conflict in Iraq could become a protracted guerrilla war, dismissing enemy fighters as little more than “dead-enders” from the Hussein era.

Eventually, Rumsfeld recognised that a tenacious insurgency had taken root, but as the violence worsened through 2004, 2005 and 2006, he resisted arguments that the US troop level in Iraq should be raised. He argued that Iraq needed to avoid developing a long-term dependence on the United States. But in the process, he underestimated the pace at which Iraq’s new security and political structures could establish themselves

Rumsfeld’s toughness won him respect among a number of senior field officers. He tended to grant commanders broad rules of engagement, backing up troops when things went wrong. “He was the kind of guy you wanted on the other end of the phone,” recalled retired general George Casey, who headed US forces in Iraq.

But all too often, Rumsfeld came across as insensitive to strains on the US military. In one much-publicised incident during a visit to Kuwait in late 2004, he told army reservists, who were concerned about inadequate armour on their vehicles, that “you go to war with the army you have”.

Donald Henry Rumsfeld was born 9 July 1932, in Chicago. His father was a real estate agent, his mother a part-time schoolteacher. Except for a few years during the Second World War, when his father was in the navy, Rumsfeld spent most of his childhood in Chicago's North Shore suburbs.

Known as “Rummy”, he was a popular student, but classmates also considered him intense and inwardly driven. He mused openly about possibly becoming president of the US.

Entering Princeton University on a scholarship, Rumsfeld studied politics.

Long after leaving college, where he met his future wife, he carried a lingering disdain of Ivy Leaguers. “He’d call them ‘reversible names’ – people with initials and all that kind of stuff,” said Ken Adelman, who met Rumsfeld in Washington in the late 1960s and became a close friend. “We talked about that hundreds of times.”

In addition to his wife, survivors include three children; seven grandchildren; and three great-grandchildren.

After leaving Princeton, Rumsfeld served as a navy pilot before landing jobs in Washington assisting two Republican lawmakers.

When a chance to run for his own seat opened up on Chicago's North Shore, Rumsfeld leapt at it. Drawing on a network of schoolmates in the area, he scored an upset win in the 1962 primary against the GOP establishment's pick and entered the House of Representatives in 1963 as the youngest Republican member.

In time, Rumsfeld emerged as a strong supporter of civil rights, a proponent of greater openness in government and a critic of the Vietnam War. He was among the first in congress to oppose the military draft, arguing for the establishment of an all-volunteer force. His hallmark issue remained congressional reform, which he pursued with typical brashness and determination. He even set a filibustering record in 1968, delaying House action on a bill through an entire night to call attention to reform legislation he favoured.

Despite his prominence in the House, Rumsfeld was unable to obtain the more senior committee assignments he sought, suspecting old guard members of manoeuvring against him. In 1969, he jumped to the executive branch, accepting an offer from the newly elected Nixon to head the troubled Office of Economic Opportunity (OEO), a freewheeling collection of anti-poverty programs.

While at OEO, Rumsfeld hired a young Capitol Hill staff aide named Dick Cheney to be his top assistant. The move began a storied relationship that spanned the Nixon and Ford administrations and had major consequences for George W Bush’s presidency, where Cheney, as vice president, became Rumsfeld’s most powerful ally and staunchest defender.

Following Ford’s ascension to the presidency in 1974, Rumsfeld returned to Washington as White House chief of staff – an assignment that placed him at the centre of one of the most wrenching governmental changeovers in US history.

“Clearly, the toughest job I've ever had,” he declared in an interview years later. “You had a president who’d never run for the office, who’d never been an executive, who didn't have a campaign team, didn't have a platform. And you had a White House that was deemed, unfairly in many respects, not legitimate.”

In late 1975, Ford named Rumsfeld defence secretary, giving him the kind of senior cabinet post he had long coveted. He used his new authority to play up a mounting Soviet threat and press for a surge in US defence spending.

After Ford’s presidency, Rumsfeld accepted a distress call from the Searle family of Chicago to take charge of their giant pharmaceutical firm, GD Searle & Co.

Rumsfeld took an axe to the company, selling off at least 20 subsidiaries, dismissing hundreds of employees and refocusing the remaining elements on several core operations.

In 1985, the sale of Searle to Monsanto transformed Rumsfeld into a multimillionaire. He earned millions more in the 1990s when he managed the turnaround of General Instrument, a cable and satellite television equipment company involved in developing HD TV.

Even while in business, Rumsfeld maintained his interest in politics and government, campaigning for Republican candidates, serving on various advisory panels and, in late 1983, accepting a six month post as Reagan's envoy to the Middle East.

On several shortlists over the years as a possible vice president, Rumsfeld made his own bid for the presidency after the sale of Searle, hoping to succeed Reagan. His campaign generated little financial support, and he withdrew from the race in April 1987.

After leaving government service for the last time in 2006, Rumsfeld established a charitable foundation that focused on supporting military families, micro-enterprises in developing countries and the former Soviet-controlled republics of Central Asia.

In a 2011 memoir, Known and Unknown, he sidestepped some of his own misjudgments and took to task a number of others – the CIA, the State Department and the Coalition Provisional Authority – for their errors in the invasion and occupation of Iraq.

Donald Rumsfeld, politician and former secretary of defence, born 9 July 1932, died 29 June 2021

Matt Schudel contributed to this report

© The Washington Post