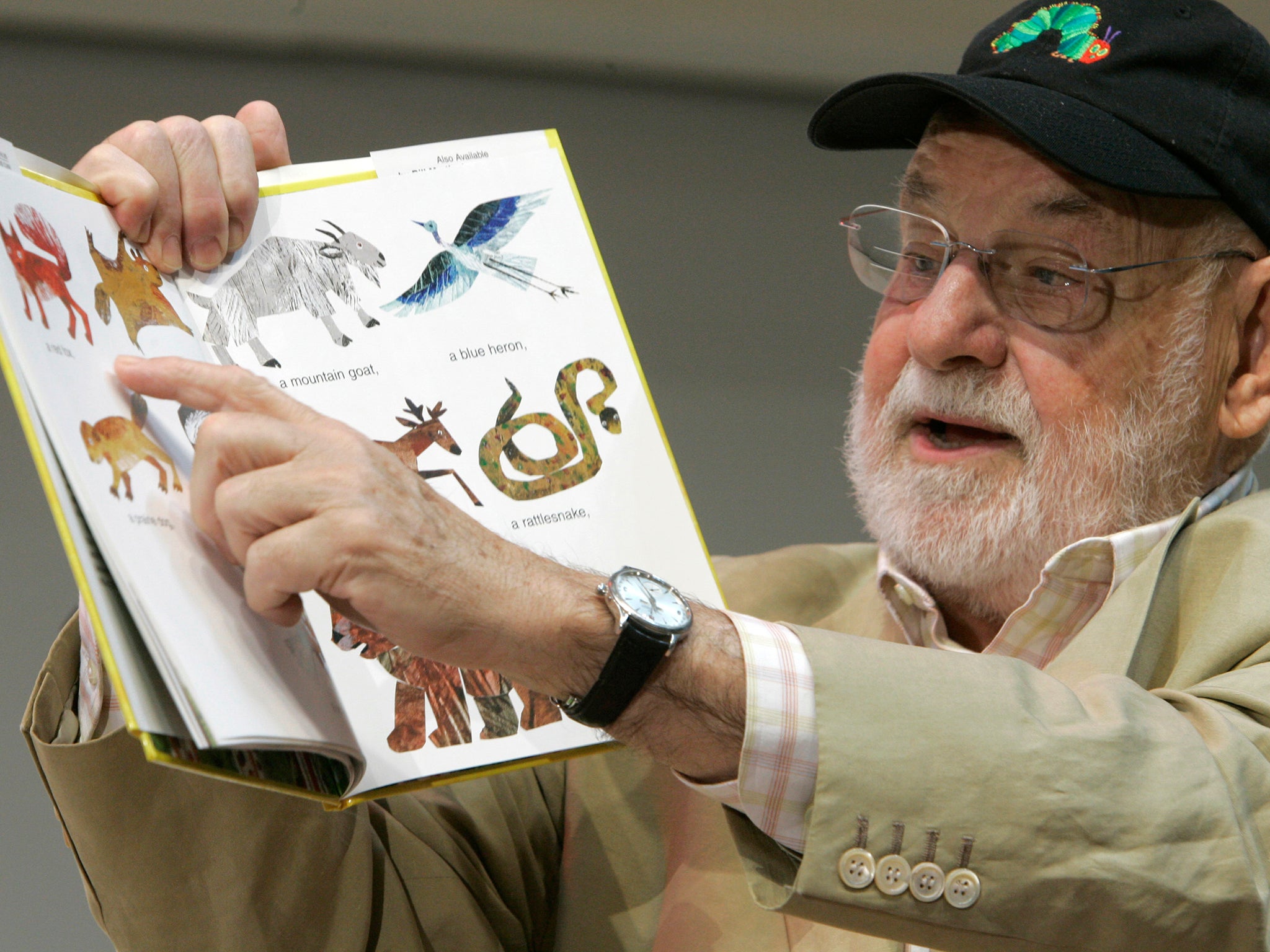

Eric Carle: Author who delighted millions with ‘A Very Hungry Caterpillar’

His whimsical picture books were enjoyed by children and adults alike for decades

Eric Carle, the writer and illustrator who delighted millions of youngsters with The Very Hungry Caterpillar and other classic picture books that captured the riotous colours and imaginative jaunts he craved as a boy, has died aged 91.

Simply told and radiantly illustrated, Carle’s books have been storytime staples for decades. Generations of young readers were enchanted by The Very Hungry Caterpillar (1969) and its ravenous protagonist, one of the best-loved characters since Peter Rabbit. On the book’s 40th anniversary, Newsweek magazine noted that it had eclipsed Goodnight Moon and The Cat in the Hat in popularity.

Many boys and girls grew up and shared the book, perhaps even the same copy, with their own children, teaching them to read or lulling them to sleep with its words: “In the light of the moon a little egg lay on a leaf. One Sunday morning the warm sun came up and – pop! – out of the egg came a tiny and very hungry caterpillar.”

In the course of a week, and in a fashion conducive to teaching numbers and days, the caterpillar consumes one apple, two pears, three plums, four strawberries, five oranges and a series of treats including chocolate cake, a pickle and a slice of Swiss cheese.

After the stomach-soothing meal of a green leaf, the satiated and no longer tiny caterpillar retreats to a cocoon before emerging as a magnificent butterfly. In Carle’s final illustration, a panorama spread over two pages, light seems to shine through the creature’s wings as if through the stained-glass windows of a European cathedral.

Carle’s works – more than 70 in all, including The Grouchy Ladybug, The Mixed-Up Chameleon,The Very Busy Spider and Does a Kangaroo Have a Mother, Too? – sold more than 170 million copies in several dozen languages.

His hallmark collage illustrations, which he created by layering hand-painted tissue paper, needed no translation. Nor did his timeless themes: the joys of discovering a world that was filled with beauty, despite the darkness he had intimately known.

The son of German immigrants, Carle spent his early years in the US, but his mother’s homesickness drew the family back to Stuttgart in the mid-1930s when the Nazi regime sent most transatlantic movement in the opposite direction. During the Second World War, he recalled hiding for hours in a cellar as bombs fell around them. Once, he said, he was wading in a river when a gunner fired on him from a plane. The shooter missed.

In his teens, Carle joined forced labourers building trenches along the Siegfried defensive line. His father, who had been conscripted into the German army, was imprisoned for years by the Soviets.

“During the war, there were no colours,” Carle once told NPR. “Everything was grey and brown … Houses were camouflaged with greys and greens and brown-greens and grey-greens or brown-greens.”

Decades later, Carle’s artwork was instantly recognisable for its palette – the shimmering silver-white of the moon, the burning yellow-orange of the sun, the luscious green of a leaf. And yet, he said, “I’m frustrated that I cannot be more colourful than I am.”

His style seemed influenced by Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse and other modern painters secretly introduced to him by an art teacher in Germany. Nazi propagandists had labelled modern art “degenerate”, and the teacher admonished Carle to not speak of what he had seen but to remember it.

In 1952, he returned to the US and pursued an advertising career in New York. He debuted as a children’s illustrator with the publication in 1967 of Brown Bear, Brown Bear, What Do You See? The book’s writer, Bill Martin Jr, had sought Carle’s collaboration after seeing his collage-rendering of a lobster in an advertisement.

Brown Bear, with Martin’s soothingly repetitive text about a menagerie of animals discovering each other’s colours, remains today a mainstay of children’s bookshelves. Its publication introduced Carle to the pleasures of creating literature for the young.

“I didn’t realise it clearly then, but my life was beginning to move onto its true course,” he observed in an essay. “The long, dark time of growing up in wartime Germany, the cruelly enforced discipline of my school years there, the dutifully performed work at my jobs in advertising – all these were finally losing their rigid grip on me. The child inside me – who had been so suddenly and sharply uprooted and repressed – was beginning to come joyfully back to life.”

Carle created a counting book, 1, 2, 3 to the Zoo, before the publication of The Very Hungry Caterpillar. In time, readers were irresistibly drawn to its luminescent colours and nibble holes playfully punched in the pages. The book also won praise for its understated literary sophistication.

“When the caterpillar turns into a butterfly it’s a joyful moment, but there’s also a lurch,” the author Emma Brockes wrote in The Guardian. “How many books for the under-fives have subtext?”

It was noted that the caterpillar’s eating frenzy seemed to recall the consumption that might follow years of wartime hunger. According to another reading, the story is a Christian allegory, an interpretation perhaps lost on the young. Not lost on them was the story’s message of hope.

“You little, insignificant, ugly thing can grow into [a] big, beautiful butterfly,” Carle said, paraphrasing his work, “and fly into the world.”

Eric Carle was born 25 June 1929 in New York. His father, who was artistically inclined and found work in the US spray-painting washing machines, instilled in him the love of nature that later infused his son’s books

“We used to go for long walks in the countryside together, and he would peel back tree bark to show me what was underneath it, lift rocks to reveal the insects,” Carle observed in the publication Books for Keeps. “As a result, I have an abiding love and affection for small, insignificant animals.”

He was six when the family resettled in Germany. He was evacuated to the countryside as the Second World War intensified and was 18 when his father came home from the Soviet camp weighing 85 pounds.

“To this day,” Carle told The Independent, “I can barely enjoy a good meal because of thinking about my father.”

Carle pursued artistic training at an academy in Stuttgart before returning to the US. Working in advertising, he told the Chicago Tribune, he “had the Brooks Brothers suits and the attache case” and “took the 8:02 every morning”. But he did not find contentment until he was presented with the text of a children’s book about a brown bear who meets a red bird who meets a yellow duck who meets a blue horse…

Working with Bill Martin Jr, Carle later illustrated Brown Bear sequels that included Polar Bear, Polar Bear, What Do You Hear? and other ursine explorations of the senses.

Carle’s longtime editor, Ann Beneduce, made a critical contribution to the creation of his most famous work. He had planned to write a picture book titled A Week With Willi Worm until Beneduce observed that a caterpillar-turned-butterfly might have greater emotional resonance than a worm prone to overeating.

Carle is survived by his two children and a sister.

Eric Carle, writer, designer and illustrator, born 25 June 1929, died 23 May 2021

The Washington Post