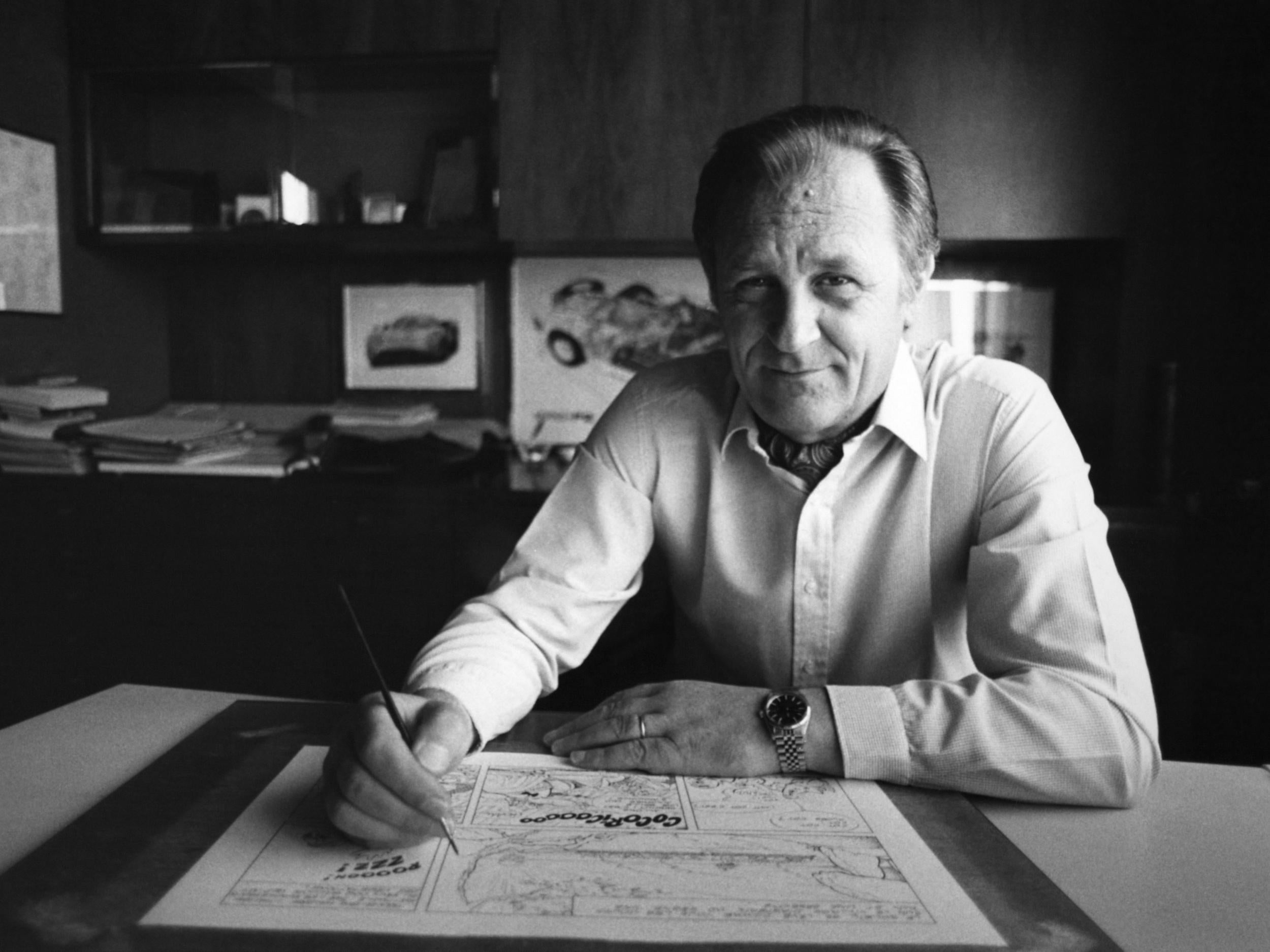

Albert Uderzo: Illustrator who gave the world the cartoon hero Asterix

He co-created the comic series that became a huge and long-lasting international success

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Albert Uderzo, who has died aged 92, was a French illustrator who co-created Asterix the Gaul, the diminutive, blond warrior who became one of the world’s most recognisable and beloved cartoon characters.

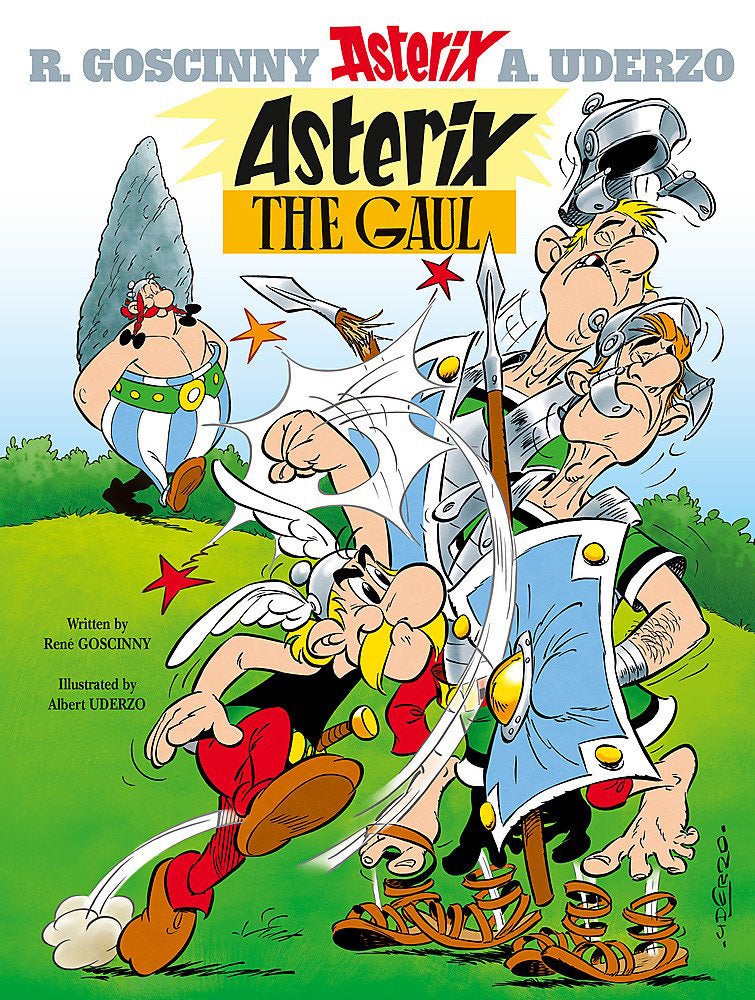

Uderzo, who was born colourblind and with six fingers on each hand, became one of the world’s most acclaimed cartoonists, known for drawing characters that ranged from the sword-wielding Asterix – with his winged helmet, bulbous nose and horseshoe moustache – to the roly-poly Obelix, a stonemason who joins Asterix in defending their village from Roman legionaries.

Created in 1959 by Uderzo and writer Rene Goscinny, Asterix served as a Gallic alternative to American cartoons like Superman and Batman, mixing sly wordplay with sight gags, Latin jokes and caricatures of French politicians such as Jacques Chirac, who made his way into the comic series disguised as a Roman economist.

After debuting in the satirical magazine Pilote, Asterix became a mainstay of French culture for more than six decades, spawning dozens of books as well as animated movies, radio and television shows, live-action films starring Gerard Depardieu and a theme park not far from Disneyland Paris – a coup for Uderzo, who modelled his cartooning style in part on the early works of Walt Disney.

The series became so popular in France that the country’s first satellite was named Asterix. And when Goscinny died, in 1977, one French obituary likened his passing to the collapse of the Eiffel Tower. Uderzo, who continued the series on his own, went on to outsell Voltaire, Flaubert, Hugo and every other French author before him, with more than 380 million Asterix books sold in more than 100 languages worldwide. In terms of raw sales figures, his hero was more popular than Tintin.

The books’ other regulars included villagers whose names constituted elaborate puns: Chief Vitalstatistix (in the original French, he was known as Abraracourcix), the elderly Geriatrix (Agecanonix), the bard Cacofonix (Assurancetourix) and the druid Getafix (Panoramix), whose potions endow superhuman strength. Together they lived in huts on the coast of present-day France, in a region Uderzo was said to have modelled after Brittany, where he waited out the Nazi occupation of Paris.

As the series took off, critics and scholars took turns tracing the appeal of a comics series set in 50BC. Perhaps it was the fact that France had recently battled foreign occupiers, or that the country was pushing back against a flood of American popular culture. Asterix was distinctively, undeniably French and – at a time when Algeria’s independence war was spurring a wave of migration into the country – seemed to speak to a more narrow definition of national identity.

“It’s a puzzle to me why Asterix happened the way it did,” Uderzo once said. “Rene and I had previously created other characters with as much passion and enthusiasm, but only Asterix was a hit. I think it’s perhaps because everyone recognises himself in the characters. The idea of the weak who defeat the strong appeals. After all, we all have someone stronger lording it over us: the government, the police, the tax collector.”

Alberto Aleandro Uderzo was born in Fismes, northeast France, in 1927, and was raised outside Paris. His father was a luthier, and both parents immigrated from Italy. He had surgery as a child to remove the extra digit on each hand.

By the age of 14, Albert – he dropped the o – was publishing his first illustrations, churning out cartoons for French and Belgian publications. A decade later he began working with Goscinny at a publishing house in Paris. They soon developed characters such as Oumpah-pah, a Native American scout, and helped to launch the magazine Pilote, where Asterix made his debut. “They wanted a comic strip with ‘French’ themes, and we toyed with ideas from different periods of history,” Uderzo said.

The duo published two dozen Asterix books, beginning with Astérix le Gaulois (1961), before Goscinny died at age 51 after a heart attack. Uderzo said he considered killing off Asterix before deciding to carry on the work alone. He spent about three months crafting each book’s story and twice as long on the drawings.

While Asterix volumes continued to sell well, some critics said the later books lacked the wit of those written by Goscinny. Uderzo handed the reins to a new creative team, writer Jean-Yves Ferri and illustrator Didier Conrad, beginning with the 2013 book Asterix and the Picts.

By then Uderzo had sold a majority stake of his publishing company, Éditions Albert-René, to the French conglomerate Hachette Livre, kicking off a bitter dispute with his daughter Sylvie, a former executive at Albert-René. In a 2009 letter published in Le Monde, she accused him of turning his comics over to “perhaps the worst enemies of Asterix, the men of finance and industry”.

A long legal battle ensued, with Uderzo suing his daughter and son-in-law for “psychological violence” before the family publicly reconciled in 2014. The episode marked a rare moment in the spotlight for Uderzo, who generally remained behind the scenes.

He is survived by his wife Ada Milani, whom he married in 1953, and his daughter.

Albert Uderzo, illustrator, born 25 April 1927, died 24 March 2020

© Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments