With low ambition and a weak economy, can Keir Starmer meet his promise on poverty?

Labour will face a tougher economy and weaker public finances than Blair did in 1997, writes Stewart Lansley. It means this could be the time for radical change, not caution

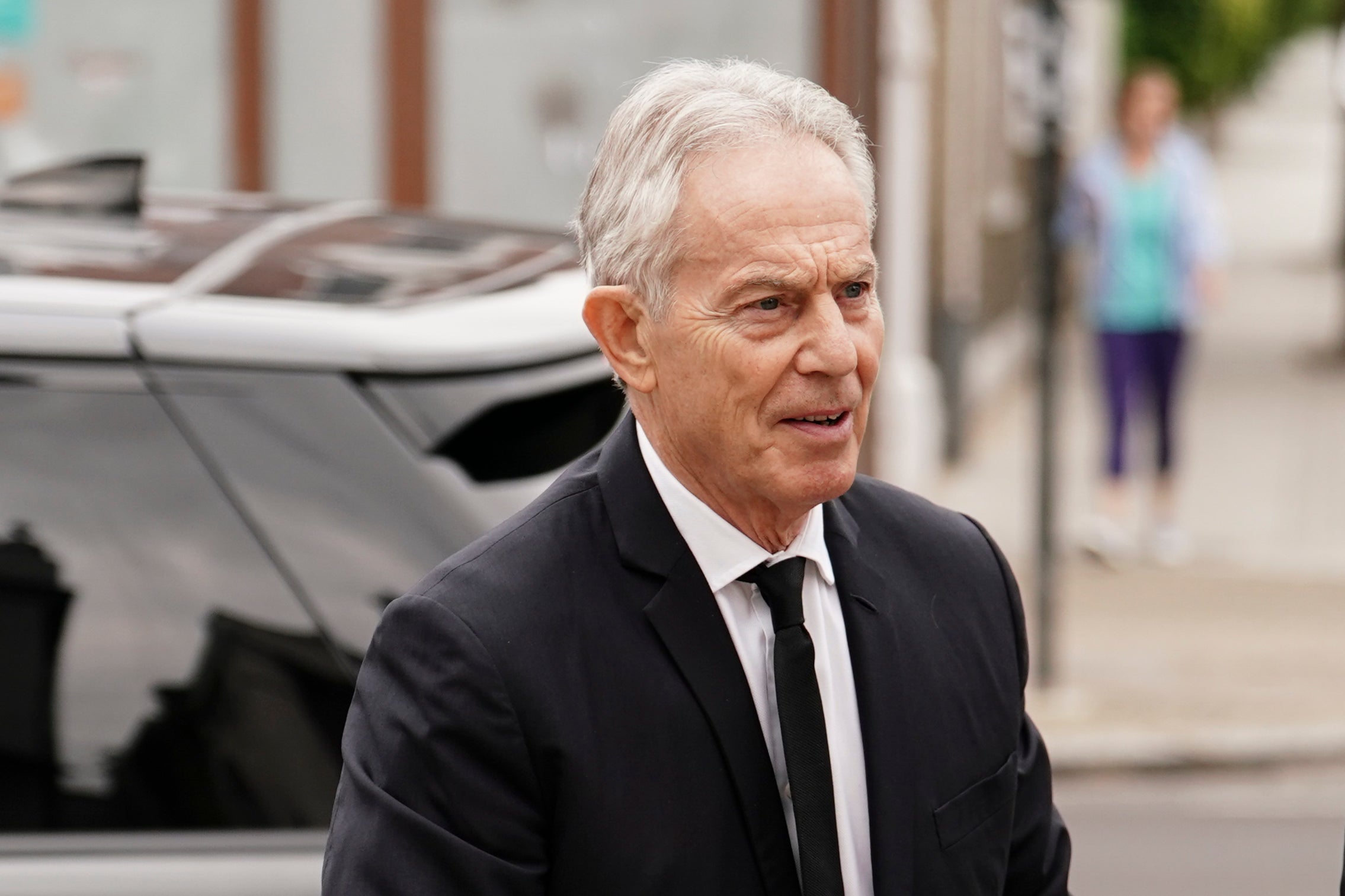

In one of his clearest promises, Keir Starmer has declared that he will be as “laser-focused on poverty” as Tony Blair. This is a welcome commitment. Nevertheless, it raises the question of how sustained cuts in poverty can be achieved without a simultaneous attack on Britain’s yawning income and wealth gap. Here the lesson of history is clear: poverty and inequality are umbilically linked. Britain achieved peak equality and a low point for poverty in the 1970s. This was the high-water mark of post-war egalitarianism and a historic achievement. But it was short-lived.

The next four decades saw a doubling in the level of (relative) child poverty and a surge in inequality. The overriding explanation for these reversals lies in the shift from an egalitarian to an anti-egalitarian philosophy of government.

“True” Conservatives need “to make the case against egalitarianism” wrote Keith Joseph in 1976. By “letting our children grow tall”, Margaret Thatcher believed that a stiff dose of inequality would boost entrepreneurialism and deliver a stronger economy that would benefit all. The economic renaissance failed to come, but the anti-equality counter-revolution has turned Britain into a high-poverty, high-inequality and economically turbulent nation, returning it to its pre-war history.

The legacy of the politics of inequality of the last four decades has been the reversal of many of the hard-fought social gains of the past. Life expectancy rates have been falling in the most deprived communities, the gap in the electoral turnout of the richest and poorest groups has widened sharply, while Britain’s system of social protection is one of the meanest and most punitive among rich nations.

The lowest levels of child poverty in Europe are found in relatively equal countries such as Slovenia, where 11 per cent of children are below the poverty line, and Finland, where it is 13 per cent, compared with the European average of 24 per cent. In Britain, the rate is 29 per cent: that is, 29 per cent of children live in households whose income is lower than 60 per cent of the median – the standard definition of relative poverty. A sustained cut in poverty is possible in Britain but it would require a fundamental shift in the way society works and an end to the mechanisms by which a small financial and corporate elite has been able to capture a growing share of the gains from economic activity.

Ultimately, the level of poverty in society depends on how the cake is shared, and thus the outcome of the conflict over the spoils of economic activity and of the interplay between power elites, governments and societal pressure. How the distribution question has been settled over time has been the central driver of the changing positions of rich and poor. Only once in modern history – in the three post-war decades – have these forces aligned to promote greater equality. While the state played a decisive role in mitigating the inbuilt bias to inequality in those decades, it has since become a key agent of inequality.

The post-1980s personal wealth explosion at the top is less the product of a surge in value-creating productive activity, which contributes to wider wellbeing, than of a process of what the 19th-century Italian economist Vilfredo Pareto called “appropriation or others extraction”. Such appropriation has become increasingly widespread in business activity. Easy money is to be had from corporate extraction. Many large companies have been turned into cash cows for a financial elite through the rigging of financial markets, and the “croupier’s take” – the skimming of returns from financial products.

A key source of this process has been the return of anti-competitive devices described as “market sabotage” by the American heterodox economist Thorstein Veblen over a century ago. In contrast to the claims of pro-market thinkers, attempts to undermine competitive forces have been an enduring feature in capitalism’s history. Instead of being used to improve wages, build economic strength and boost investment, rising corporate profits in recent decades have been used to boost dividend payments to shareholders and to feed the executive gravy train.

Such extraction has sapped social resilience and economic strength, diverted scarce resources from more productive activity and contributed to Britain’s low investment, low wage, low productivity economy. Cutting poverty levels depends on ending the mechanisms of personal enrichment that undermine wider living standards and life chances.

Blair, following Thatcher, bought into the argument that surging rewards at the top were deserved, and poverty had nothing to do with the process of wealth accumulation

Blair’s ambitious post-millennium goal to abolish child poverty over time offers important lessons. It achieved some notable, but only temporary successes. It ultimately failed because Britain’s inequality-driving and stability-sapping model of extractive capitalism was allowed to continue unchecked. Blair, following Thatcher, bought into the argument that surging rewards at the top were deserved, and poverty had nothing to do with the process of wealth accumulation. As Blair put it, “I always thought my job was to build on some of the things she had done, rather than reverse them.”

A laser-focused approach would require lifting the income floor and lowering the ceiling, with both income and wealth distributed more equally. A radical approach would be to introduce a guaranteed, no questions-asked, non-means-tested income floor as a right of citizenship. This would create a “Plimsoll line” for incomes, below which no one would fall.

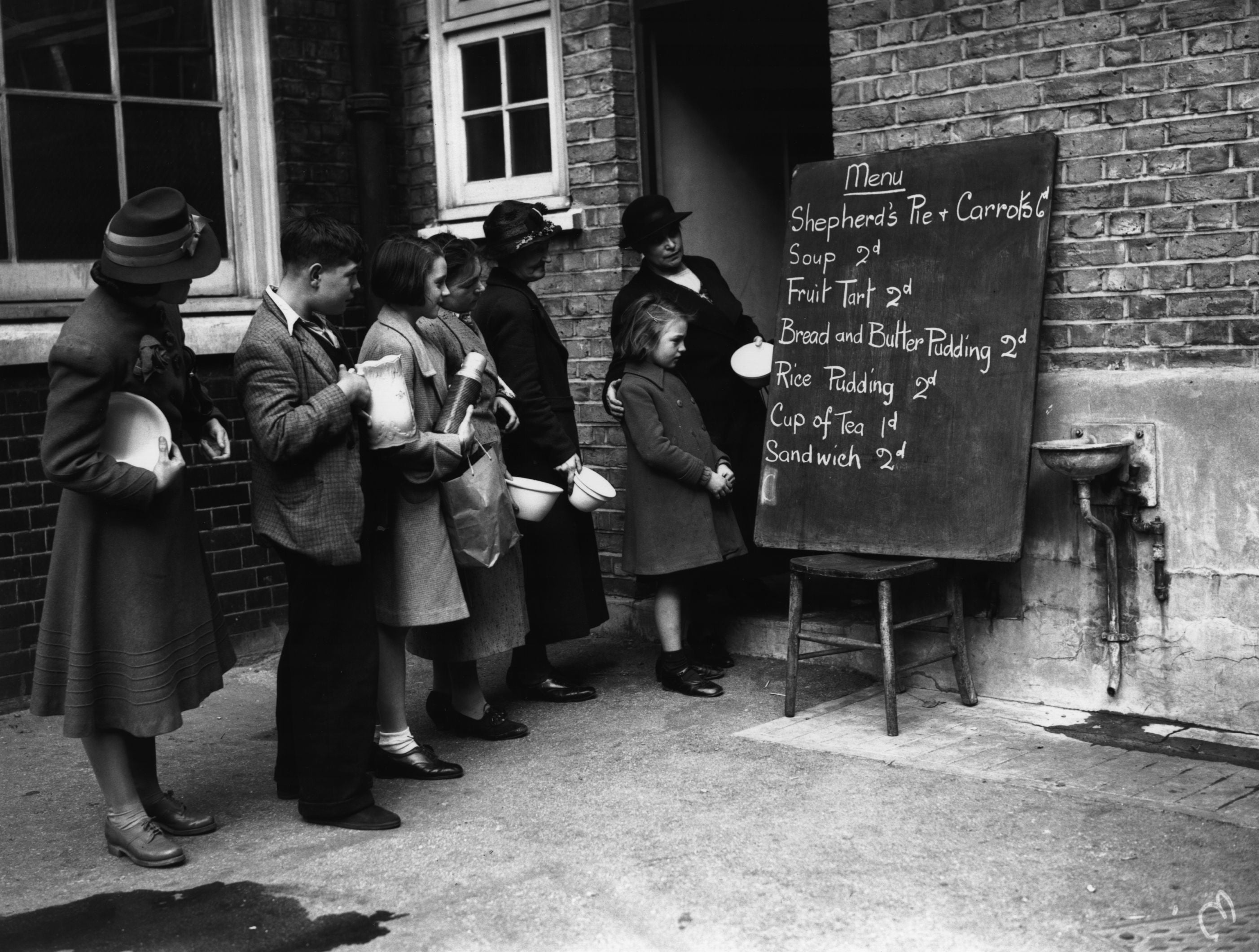

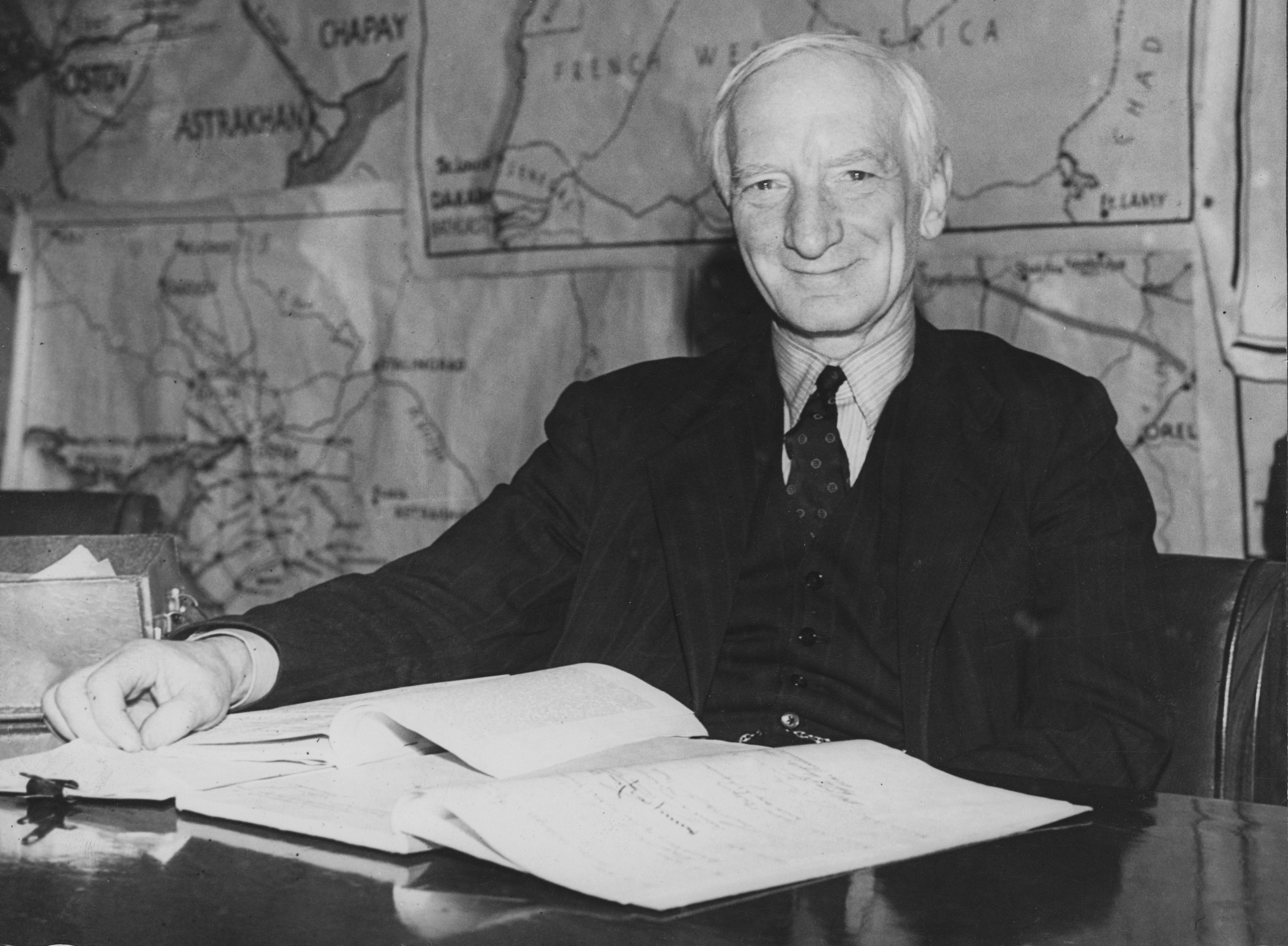

Social reformers have long called for such a guarantee and William Beveridge – who warned against “patching” – believed his 1942 plan would deliver it. Yet 80 years on, we are still far from ensuring such a guarantee. Such a floor would be more costly than tinkering with universal credit but would be a powerful anti-poverty measure that would extend the principle of universalism, boost income security and raise personal empowerment.

One study has found that even a modest basic income scheme could cut child poverty by more than a half, taking it to a historic low, below that achieved in 1977. The high up-front gross cost of such a guarantee could be met in full through tax changes that would restore the redistributive power of the tax-benefit system, which has been so badly eroded over time. Inequality would be lowered with the payment clawed back from the highest earners and the gains concentrated amongst those on the lowest incomes.

The message from 1945 is that progressive change requires a revival of egalitarianism, with a new set of embedded pro-equality and anti-poverty measures backed by public consensus

But raising the floor is only part of the answer. A sustained attack on poverty and social injustice also depends on ending the extractive practices of big business and the pro-rich, anti-poor politics of recent decades. The message from 1945 is that progressive change requires a revival of egalitarianism, with a new set of embedded pro-equality and anti-poverty measures backed by public consensus.

Such a strategy needs to recognise the critical effect of the process of wealth accumulation at the top on low incomes at the bottom. Alongside a higher and guaranteed income, such measures should include a new system of asset redistribution aimed at mobilising Britain’s massive private wealth mountain for social reconstruction, a war on corporate appropriation, and a new priority to unmet social needs.

Starmer has made some hints of the need for change, including a call for a new Beveridge blueprint. But such calls lack detail, while even bits of tinkering – such as the abolition of the punitive two-child limit, which has applied to third and subsequent children born since April 2017, and the extension of free school meals among primary school children – are being ruled out.

On the income and wealth gap, Labour is promising to scrap private schools’ tax breaks, raising up to £1.5bn a year, and the non-dom tax status to wealthy residents whose permanent homes are abroad. Other anti-inequality policies such as higher taxes on the rich, including on wealth (much of it unearned), have been discounted. Yet wealth taxes currently raise a tiny fraction of state revenue and even modest increases could generate funds to finance a significant boost to social reconstruction.

Labour will face a much tougher economic environment and greater fiscal constraints than in 1997, with a much weaker set of public finances. As in that year, the party has said it will initially stick with current Tory spending plans – and the built-in austerity they imply – if elected. Shadow cabinet members are being warned there will be no more cash for the NHS, schools, local councils or public sector pay, while the new investment in a green economy will have to wait.

The primary reason for such caution is that Starmer and Rachel Reeves think that Labour is politically vulnerable on public spending. They distrust economic thinking that doesn’t fit the gameplan, while succumbing to the Treasury line that priority needs to be given to fiscal prudence and the reduction of the budget deficit, thus ignoring the evidence that the long post-2010 austerity programme brought prolonged stagnation and was slow in lowering the deficit.

Starmer’s promise on poverty is at odds with this wider caution. Labour is putting all its faith in growth, but has yet to accept that higher public investment offers the clearest route to rebuilding a broken economy and fractured society. The contradiction at the heart of Labour’s emerging strategy is that prioritising fiscal balance to cut the national debt is at odds with both the anti-poverty and the boosting growth goal.

Labour’s strategy in the 1960s and 1970s – years of egalitarian optimism – was that sustained economic growth was necessary to secure redistribution without resistance from higher-income groups. Between 1951 and 1976, two-thirds of the proceeds of growth were spent on boosting the social wage through better public services and building a stronger welfare state (even if spending on defence still took a significant share of all public spending).

Labour is putting all its faith in growth, but has yet to accept that higher public investment offers the clearest route to rebuilding a broken economy and fractured society

If the economy begins to expand more quickly through new forms of wealth creation, this would make the changes needed easier to implement. But if today’s lower growth rates persist, the post-1945 strategy will no longer work, and the priorities of economic and social policy will need to be rethought. The political choices – to find ways of steering more resources into meeting basic social needs through changes in tax and spending policies, investment and business strategy – will be tougher but no less necessary.

The political risk with over-caution and under-promising is that it looks low on ambition. Just how much difference would one or two terms of a Labour government make? The evidence is that large sections of the public are hungry for change and would respond positively to radicalism. Because of austerity, Britain has comparatively low social and infrastructural spending levels and is one of the most heavily privately owned and weakly regulated economies among rich nations.

The overriding priority is to make the state an agent of equality again. This means tougher regulation to end the process of extraction and steer resources into more socially productive uses, and a reversal in the politics of distribution. It would mean a switch away from the overwhelming dominance of private and individualised property rights and a greater emphasis on collective property ownership, so that the gains from wealth holdings are more equally shared through regulation, socialisation and appropriate taxation. Labour’s credibility as a party of change depends on delivering tangible improvements, a fairer society, better-funded public services and a less rapacious model of capitalism. Failure to do so will further imperil Britain’s already insecure future.

Stewart Lansley is a visiting fellow at the University of Bristol and has written widely on wealth, inequality and poverty. His latest book is ‘The Richer, The Poorer – How Britain Enriched the Few and Failed the Poor. A 200-Year History’, published by Policy Press

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments