The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

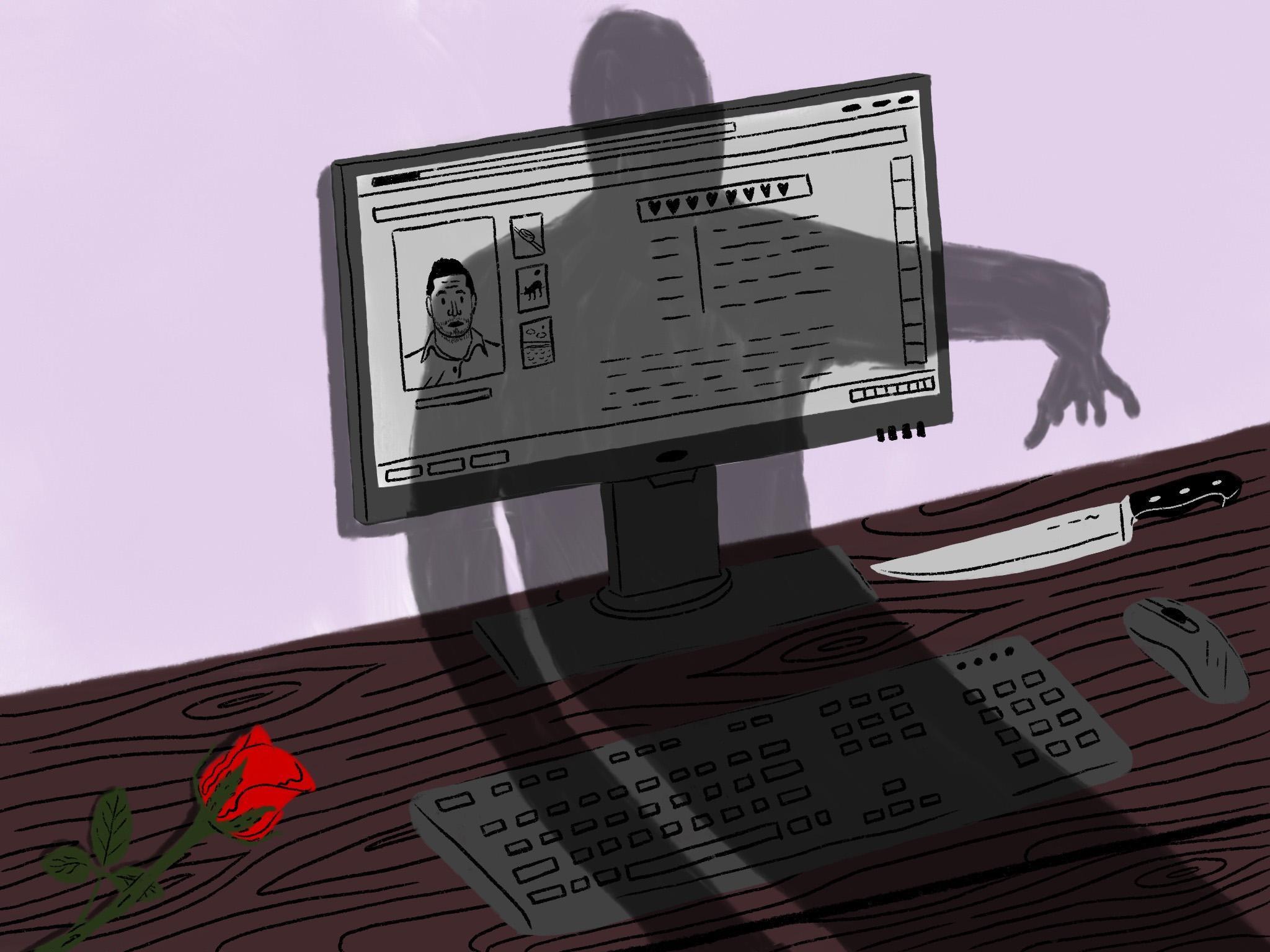

The lies we tell on dating apps show we haven’t really changed at all

As more and more people find love online, others are learning how to exploit dating apps for their own – sometimes dark – motives. But apps aren’t responsible for the terrible acts humanity is capable of committing, says crime fiction writer Kristen Lepionka. The real problem has always been that people are just awful

One of the first mystery novels I ever read was Mary Higgins Clark’s Loves Music, Loves to Dance. This 1991 bestseller centres on a clever killer who finds his murder victims in the personal ads of a trendy magazine. I was probably eight or nine when I read this book (don’t ask) and the little I knew about personal ads I’d learned from the Rupert Holmes song “Escape”. But if he could accidentally go on a blind date with the pina colada-loving woman he was already seeing, it certainly seemed believable that someone could accidentally go on a date with a murderer.

You might think that a story like Loves Music, Loves to Dance couldn’t take place in the internet era. A personal ad in a print publication is one-way, a broadcast signal, belonging to a time when letters and answering services were a thing, when an entire meet-cute (or mystery novel, for that matter) could hinge on whether or not someone happened to be at home to receive a phone call at a particular time. By contrast, the digital iteration of personal ads is all about instant communication. We can text, WhatsApp, FaceTime, like, favourite, and swipe all day every day, and we can get a true sense of what someone is like based on the information they’ve put online instead of relying on a few lines of text in the back of a magazine. So this should make sussing out the weirdos and creeps easier.

It actually just makes it harder.

As a crime fiction writer, I routinely traffic in weirdos and creeps. A lot of interesting stories start at the place where you realise someone isn’t quite who they claim to be – in fact, that might be at the cold, black heart of every single crime novel out there. When it came to the third novel in my Roxane Weary mystery series, I wanted to explore the layers of deceit in modern relationships, which meant I wanted to take a deep dive into the world of online dating.

I’m happily spoken for and have been since 2011, but before then I dabbled just a little in Craigslist personal ads. Before I go on about how Craigslist personals are so unbelievably sketchy that the site actually removed the ability to post them, I’ve made multiple lasting friendships through the “strictly platonic” section. So the experience wasn’t all bad. I did not meet any romantic soulmates this way though; I only ever went on one second date with anyone, a girl named Suzanne who showed up to said second date already drunk and then got mad at me for having seen Avatar without her and never emailed me again. When I started researching for The Stories You Tell, I quickly discovered that everything in the online dating world had changed (while, also, nothing had).

There are an awful lot of dating apps a person can explore. They include options like Tinder, Bumble, Hinge, Plenty of Fish, Christian Mingle, Our Time, Match.com, eharmony, Zoosk, OkCupid, Grindr, Coffee Meets Bagel, plus a couple dozen more you probably haven’t even heard of. Whether you seek a late-night hookup, a quick breakfast date, or a match based on sun signs, there’s a particular dating app for you. They each have their own particular demographic and approach, but the basic principle is the same: users create a profile that shows themselves in, ostensibly, the best possible light, and attempt to connect with other users who’ve done the same.

More people are finding love this way these days – one in three relationships in the UK start online (and it’s even higher in the US, at two in five). As these types of connections become more and more commonplace, it unfortunately makes sense that some people are increasingly more likely to exploit them. Here are a few that I came across during my research:

- The “Craigslist Killer” Philip Markoff murdered three women he had met on Craigslist in New England in the space of a few days in April 2009. Books, made-for-TV movies, and multiple docu-series episodes about this case have come about in the decade since.

- Adam Hilarie met a woman through the dating site Plenty of Fish and took her bowling; the date seemed to go well, because the woman texted him later, saying, “I had a good time and would like to see you again”. But the following night, his date showed up at his house with two male accomplices and, after robbing him, shot him in the head.

- Sydney Loofe met a woman on Tinder and they hit it off. But when they met up for a second date, Loofe was killed and dismembered by her date and an older male accomplice.

- Mediterranean island Cyprus experienced its first ever serial killings thanks to online dating sites and the 35-year-old army officer who used them to find the seven women he confessed to murdering.

- Nurse Samantha Stewart was murdered by her Tinder date who then used her credit card to flee cross-country to Los Angeles, where he was later arrested – with another woman found tied up in his hotel room.

- Usha Patel was stabbed to death in her home after inviting an online paramour over.

- Meshach Cornwall invited over a woman he met on Plenty of Fish and they spent the night together. She returned two days later and robbed and killed him, making off with cell phones, guns, a television and a car.

Unfortunately, there are a lot of these stories. But online dating isn’t responsible for the terrible acts humanity is capable of committing. The real problem, when you get right down to it, is that people are awful. Hashtag optimism. Hip-deep in research at this point, I knew the story that I wanted to tell existed in the liminal space between in-person and online. In addition to amassing this very bleak list of crimes, I also did some hands-on exploration.

Tinder is one of the most well known of the myriad dating apps, and I don’t doubt that meaningful connections can be found there, but the information users provide on their profiles is limited to: a 500-character description (that’s less than two full tweets), basic stats – like job title, alma mater and sexual orientation – Instagram and Snapchat profiles, Spotify playlists, and the all-important photos. Can you get a good sense of a person if they’ve included all of that? Definitely. Is everyone including all of that? No.

A lot of interesting stories start at the place where you realise someone isn’t quite who they claim to be – in fact, that might be at the cold, black heart of every single crime novel out there

I created a “test” profile (read as “fake”) for the purposes of exploring the functionality of the app. I grabbed a photo from free stock image site Unsplash (featuring a kind-looking young woman in heart-shaped sunglasses), decided that she was a bisexual 27-year-old tutor named Fran, and used a Neil Young lyric as the entirety of her description. The app suggested that I link Fran’s Instagram and Snapchat profiles (impossible since she doesn’t exist, and also because I barely know what Snapchat is) and that I upload more than one picture, perhaps trying to encourage me to present a well-rounded portrait of myself. I didn’t have another picture of the sunglasses lady, so I took a picture of a bottle of hot sauce from my pantry and called it a day.

Upon completing this very (very) minimal profile, I started swiping. It’s really quite strange, this idea. Right for yes, left for no. The main screen places the first half of the user’s description over the bottom part of the photo. If you want to read the rest, you can – it’s somewhat hidden under a tiny “information” icon in the corner. It’s worth noting that even though the description is a max of 500 characters, some users haven’t bothered to put anything there. If you swipe right on someone who also swipes right on you, the app informs you that you’ve made a match. And then it’s up to you to send a message to the person to get going on your happily ever after.

(It’s worth noting that there is no “skip this person” option. This is not the time to stay neutral.)

Fran proved to be pretty popular. Within a few minutes, the app told me that she’d already had 20 likes. Basic users of the app can only see who has liked them if the swipe is mutual, but you can also upgrade to various premium (thanks, late-stage capitalism) options to see everyone who has swiped right on you. By the end of my Tinder research, Fran had 99+ likes.

The thing about this that scares me the most is that the Fran profile is so obviously fake that I was embarrassed to use it. I have no earthly idea how anyone could look at this and believe Fran to be a real person.

It’s possible that no one is thinking about it all that much – just assuming, “here’s a pretty face. I like pretty faces” and swipe. Or maybe the users who swiped right on Fran really like Neil Young, or hot sauce, or tutors.

Or maybe these users weren’t looking for a date either. They probably weren’t also researching for a crime novel, but there’s an element of slot-machine mindlessness to the swiping – it’s hypnotic, maybe even fun, if you aren’t thinking about it as work.

Above all, it’s easy.

Maybe that’s the most sinister element of all. We used to have to work a lot harder to make connections like this – exchange a series of letters, a phone call, an in-person conversation. Now we can anonymously pass judgment on strangers for however long we’d like (users spend an average of 10 hours per week doing this) with no stakes and no pressure.

There’s not exactly an incentive to be honest online. It’s usually harmless – lying about your natural hair colour or how much you like Bon Iver is unlikely to hurt anyone. But putting yourself out there in the vulnerable space of looking for love can risk much more than your tender human heart, as the characters in The Stories You Tell quickly find out. Dating apps aren’t inherently dangerous, but rather it’s the deception that some people engage in while using them that creates the danger.

So despite the modern coat of paint on the way we communicate with each other, there’s nothing more timeless than the idea of people lying to each other.

The Stories You Tell by Kristen Lepionka is published by Faber and Faber (£8.99)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments