Way out West: what does having Kanye for a neighbour mean for the people of Cody?

‘Everyone who hopes that Kanye will bring jobs to town is aware that they’re taking an emotional gamble, especially given how frequently he changes his mind.’ Jonah Engel Bromwich finds out about the impact the celebrity is having on a small town in Wyoming

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It’s surprising that a global celebrity who frequently self-identifies as the greatest artist living or dead has become an everyday presence in a tightly connected town of about 10,000 people. It’s more surprising just how much the town’s leaders want him to stay.

There Kanye West is at the McDonald’s, the Best Western and the Boot Barn. He hangs out at the Cody Steakhouse on the main drag, where he met one of his intern videographers, a student at Cody High School. His ranch is close to town, and to get where he needs to go, Kanye drives around town in a fleet of blacked-out Ford Raptors, the exact number of which is a topic of local speculation. Gina Mummery, the saleswoman at the Fremont Motor Co dealership, would say only that she sold him between two and six.

Kanye started taking trips to Wyoming regularly in 2017, shortly after he was hospitalised for what was characterised in a dispatch call as a “psychiatric emergency”. He spent lots of time making music in the state in 2018, holding an incredible listening party for his album Ye in late May in Jackson, a town famous for its skiing, fishing and ultra-wealthy residents.

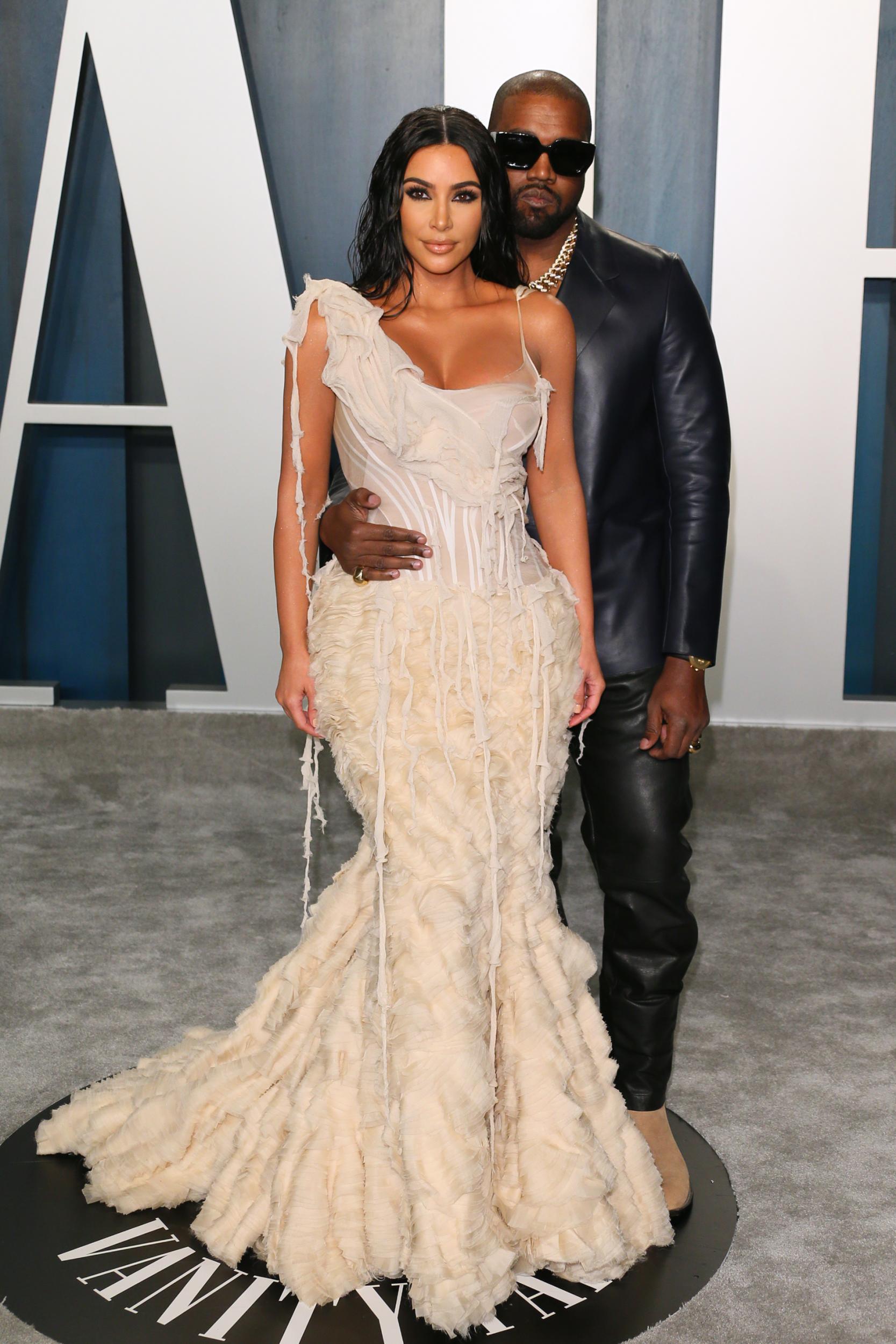

And then, in September, the Cody Enterprise reported that he’d bought a property called Monster Lake Ranch, about eight miles outside Cody, which is a five-hour drive northeast from Jackson. Suddenly, he and his family, including his spouse, Kim Kardashian West, who is an entrepreneur, television star and law school student, were there: zooming around on four-wheelers, crashing wedding preparations and shopping for clothing and jewellery on the town’s main street, Sheridan Avenue.

Since then, Kanye has recorded portions of his ninth studio album, Jesus Is King, in Cody. He purchased about 11 acres of commercial property within the town’s limits. He also purchased a second ranch about an hour away in the town of Greybull. He has moved members of the Yeezy team into the area. In plans submitted to the city, he has detailed his intention to establish a prototype lab for the brand, in a warehouse on Road 2AB.

Kanye has announced so many plans. That he wants to start a church. That he plans to run for president in 2024. That he will invent a method for autocorrecting emoticons

And he has been characteristically forthcoming about his long-term intentions. He has talked about going from “seed to sew” in Cody – that means farming the raw material and doing the manufacturing all in one place. He’s said he hopes the town will be for him what Dayton, Ohio, was for the Wright brothers.

But in the past several years, Kanye has announced so many plans. That he wants to start a church. That he plans to run for president in 2024. That he will invent a method for autocorrecting emoticons. That he aims to redesign the standard American home. That he might legally change his name to “Christian Genius Billionaire Kanye West” for a year. It can be hard, with Kanye West, to separate concrete plans from jokes, fancies or outlandish aspirations. For now, the people of Cody have to wait and see what develops.

Even if it were just a place to relax, Cody is a cheaper escape than places like Jackson. “He’s doing things up there that would have taken another zero to do down here,” said Matt Faupel, a Jackson Hole real estate broker. The snowcapped forests and mountains northwest of Cody do attract plenty of people with money. Those with luxury ranches near town include Bill Gates and Herbert Allen, the financier best known for throwing a highly exclusive summer conference for the wealthy in Sun Valley, Idaho. Warren Buffett is also a frequent visitor.

Unlike Kanye, these men often slip in and out of the area unseen, leaving residents at a remove. “I’ve lived here all my life. I haven’t seen them,” said Dick Nelson, the 79-year-old chairman of the board of a local bank.

Still, some of Cody’s more prominent residents – including those who claim lineage of the town’s founder, Buffalo Bill Cody – haven’t met Kanye, yet. The people who serve food and drink and sell cars and Sherp all-terrain vehicles have. Tyler Stonehouse, a salesman at Whitlock Motors and sometime employee of the Cody Steakhouse, said that “there’s not an easier guy to talk to”.

Stonehouse, 30, is in recovery from drugs and alcohol. “Kanye is all about that,” he said. “I told him my whole story and he told me about his.”

Of course, there are surreal moments when chatting with a global superstar.

“Just in a casual conversation, he’s like, ‘Hey, this is my buddy, Rick, you know, and I started talking to this guy and making jokes because that’s my dad’s name,” Stonehouse said. “And turns out it’s Rick Rubin.”

The Cody Enterprise, which publishes in print twice a week, has refrained from printing local gossip about Kanye, even though its building sits several lots down from the celebrity’s commercial property on Big Horn Avenue.

But where the paper’s reporters have been circumspect, its columnists, letter-writers and commenters have flooded the Enterprise with their takes on the Kardashian-Wests. The conversation was kicked off by Doug Blough, a regular columnist for the paper, who worried that the celebrity couple would clog the town with “paparazzi, movie stars, directors and Victoria Secret runway models.”

“I’m sure you’re heard the hubbub and hoopla going around our little town this week,” he wrote in September. “If not, here’s a couple hints: he’s a famous, self-absorbed rapper who thinks homeboy Donald Trump is the cat’s meow, and she’s got a keester that knocks cans off grocery store shelves.”

He’s a famous, self-absorbed rapper who thinks homeboy Donald Trump is the cat’s meow, and she’s got a keester that knocks cans off grocery store shelves

The condemnation was swift. One letter-writer chastised the paper for allowing Blough to “make fun of a new family in our community”, saying she wanted her 75 cents back. “We do not know the hearts of famous people or non-famous people moving to our town,” she wrote. “People who move here, do so because they are attracted to this way of life that we all hold dear. Mutual love for freedom, tolerance, nature and wide open spaces, draw us to Wyoming and keep us here.”

In December, the Cody Enterprise reported that construction of a meditation centre on Kanye’s ranch was thwarted by birds. The structure, proposed to be a 70,000-sq-ft concrete amphitheatre, was complicated by a statewide order to protect a threatened species called the sage grouse, a grass dweller with the stature of a chicken and the strut of a peacock.

“I felt like it was distasteful,” Rand Cole, who helps to manage the local cemeteries and works part time as a personal trainer, said of the sage grouse coverage. “Because he’s famous they put it in the paper. Had that been someone like me, that’s not going to be in the newspaper.”

It wasn’t the first time Kanye had run afoul of the Wyoming Game and Fish Department. In one of the earliest video clips the West family filmed in the area, Kanye and Kim can be seen in what looks to be a four-by-four, driving briefly behind and then alongside a flock of antelope, known as pronghorns.

The video attracted the attention of the authorities, and a Wyoming Game and Fish law enforcement officer paid a visit to the ranch, which has been renamed West Lake Ranch. Sara DiRienzo, a spokeswoman for the agency, said that the officer delivered an official warning – chasing pronghorns is a form of wildlife harassment – but no citation.

They worry that dealing with sage grouse-related-regulation – and other such headaches – may dampen Kanye’s enthusiasm for the town

“He was not doing anything different than everybody local probably does at some time or another, internationally or not,” said Rebecca West, who is no relation and is a director and curator at the Buffalo Bill Centre of the West, where Kanye held a surprise Sunday Service, one of his gospel concerts that were held throughout 2019.

“It just happens,” she said of the accidental pronghorn harassment. “It’s part of the learning experience. You see a group and they’re running. Just stop and let them do their thing.”

For the town’s leaders, incidents like those with Wyoming Game and Fish cause concern. They worry that dealing with sage grouse-related regulation – and other such headaches – may dampen Kanye’s enthusiasm for the town. “It’s a little nerve-wracking,” Mayor Matt Hall said, sitting next to the framed portrait of a sage grouse that hangs in his office. “When he does run into those things, I’m at least there. He’s called me on at least one occasion to try and help work it out.”

Hall’s desire to keep Kanye happy has much to do with the economy of Wyoming, which is at a crossroads. Cody is near Yellowstone National Park, and so its biggest industry is tourism. On summer weekends, its population can grow by about 50 per cent, with visitors stopping in to see the rodeo and the nightly recreations of Old West gunfights before heading west to the park.

Still, Cody’s economy has long been yoked to the oil and gas industry (a little more than half of the state’s annual revenue comes from natural resources, including oil, gas and coal). Once-major employers, including Marathon Oil, have moved out of the Cody area in the past decade, leaving hundreds of employees scrambling for work.

“There is an employment deficit that we deal with in this community,” said Hunter Old Elk, 25, who works full-time at the Buffalo Bill Centre. “You have many people who work several part-time jobs.”

James Klessens, the head of an organisation called Forward Cody, hopes to expand manufacturing in the area. Klessens and Kanye have spoken about transforming Cody into an old-school company town with a Yeezy-powered economy, but said he didn’t know anything further than what Kanye had made public.

Buffalo Bill advertised Cody in a Wild West show programme, promising air that was ‘so pure, so sweet and so bracing’ that it would act as an intoxicant to city-clogged lungs

“I’m in the business development business so when I deal with a business about their business it is just that: their business,” Klessens said. Klessens spent more than a decade trying to bring pharmaceutical industry to Cody. In 2007, a local opioid-maker, Cody Labs, was acquired by the Philadelphia-based conglomerate Lannett. “It was an awesome economic development project for a rural community. We went all in with this project,” Klessens said.

But as the opioid crisis deepened; the prices of Lannett’s drugs rose sharply. The company attracted scrutiny from the press and lawmakers. Multiple investigations were launched. The company faced lawsuits, including at least one accusing it of price-fixing. In June, it announced that it was shutting down Cody Labs. “Economic development is a marathon, not a sprint,” Klessens said. “That’s why when things fall apart, it’s such a blow.”

Two months later, he received a phone call from a New York number that he didn’t recognise. The person at the other end asked him if he had a moment to speak to Kanye West.

Cody was brought into being by Buffalo Bill Cody, another bombastic showman who was, in the second half of the 19th century, the biggest celebrity in the world. More famous in his time than Theodore Roosevelt and better-travelled than The Grateful Dead in ours, Buffalo Bill basically invented the fantasy of the American West through his touring Wild West Show.

Founding a town in Wyoming was just one of Buffalo Bill’s many late-life enterprises. It has proved, in some ways, to be his most concrete legacy. Cody was incorporated in 1901, becoming “the new centre of William Cody’s continuing, almost manic entrepreneurialism,” historian Louis Warren wrote in his 2005 book Buffalo Bill’s America.

Buffalo Bill advertised Cody in a Wild West show programme, promising air that was “so pure, so sweet and so bracing” that it would act as an intoxicant to city-clogged lungs. In reality, the settlement was plopped down in the arid Big Horn Basin where the wind rarely stops blowing and there was once so much sulphur in the river that it was known as Stinking Water.

The town wasn’t even properly irrigated. By 1910, Warren wrote, “Cody and his partners had been sued at least twenty-six times.”

Buffalo Bill, under pressure, ceded the right to develop the town to the US Reclamation Service. He died in 1917 but Buffalo Bill’s spirit is alive in Cody. A half dozen people who say they are his descendants live here, including Bill Garlow, who owns the Best Western Sunset and the Best Western Ivy, an occasional hangout for Kanye and his employees.

Were Kanye interested in doing so, he could singlehandedly transform Cody, said Robert Godby, a professor at the University of Wyoming and the deputy director for the school’s Centre for Energy and Regulatory Policy. “It’s a small community, so it doesn’t take a lot to turn the boat,” Godby said. “One person can make a difference.”

Hall, the mayor, is expecting at least some modest tourism growth. Of Kanye’s presence, he said, “I’m kind of at least hoping that it can bear a little bit of fruit for the town overall.”

Kanye’s team was spotted cleaning up roadside trash, a win in any community

That idea is a worst-case scenario to others. In January, the Cody Enterprise printed a letter from a writer who expressed his disappointment that Kanye and Kim West were “starting to diminish the authenticity of the state” and said he was “heartbroken to see the real Wyoming may no longer be a tourism draw for me and others”.

A columnist, Lew Freedman, responded at length: “Saying West’s arrival means Wyoming is no longer worth visiting on vacation is preposterous.” He added: “There is inevitably an undercurrent of racism attached to this too, because West is African-American.”

Cody is about 92 per cent white; a reporter for Billboard who visited last October spoke to residents who associated Kanye’s presence in town with racist tropes, such as increased crime levels. Old Elk, who is an indigenous woman of the Crow and Yakama nations, bristled at any attempt to “typecast Wyoming as a place of intolerance”.

“Of course, you’re going to find people that have certain biases,” she said. “You try your best to speak to those people and understand that hate is at the root of a lot of that, hate and ignorance.”

“Is there room for more racial equity? Absolutely. Across the board, the state needs more people of colour and people of different religions. But you can’t make people move here. You have to create a community that’s inviting of that,” she said. “That’s true of any American town.”

For now, the Wests continue to win Cody over. When, in November, Kanye rented out the auditorium of Cody High School to piece together and rehearse his debut opera, Nebuchadnezzar, he was “very open to letting kids come in and watch,” said Cody High’s principal, Jeremiah Johnston.

One student, Kate Beardall, played with the orchestra when an extra saxophonist was needed. She told a local news station that the experience had been life-changing. “They just really just opened my eyes to what I want to do,” she said of Kanye’s crew.

Kanye’s team was spotted cleaning up roadside trash, a win in any community. “We notice those little things,” said Tina Hoebelheinrich, the executive director of the Cody Chamber of Commerce. Actions like these mattered far more to the town than Kanye’s celebrity, she said.

Even Doug Blough, the newspaper columnist, announced that he had changed his mind. In a column about his end-of-year regrets, he listed the “Kanye-Kim column that drew a smattering of boos”. After he published the column, he wrote, the bowling league had given him a “unanimous ‘too mean; not funny’ thumbs-down” on his article.

More to the point, he wrote: “I’m actually becoming a Kanye fan and watched Kim on a talk show to see if she’d talk about Wyoming. Indeed she did.”

Everyone who hopes that Kanye will bring jobs to town is aware that they’re taking an emotional gamble, especially given how frequently he changes his mind. (A representative of Kanye reached out, he agreed to talk for this story, and then did not.) Klessens said that those gambles are always part of the business but that it never gets easier.

“You have to really guard against the euphoria of the potential,” he said. “I’ve spent 32 years struggling with that problem. It’s really easy to get excited about good projects.”

John Malmberg, the publisher of the Cody Enterprise, said that the town needs any economic stimulus it can get but that there were plenty other things important to Cody. “Grizzly bears is probably a bigger story here that impacts more people,” Malmberg said. “They come down and attack people and chew them up. In the park they killed and ate a person. Those are bigger stories than Kanye West.”

© The New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments