Sitting Bull, Buffalo Bill and the circus of lies

A new book describes how Native American culture was consumed and repackaged by show business. Its author, Eric Vuillard, explores into the relationship between two of the main characters in this travesty

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

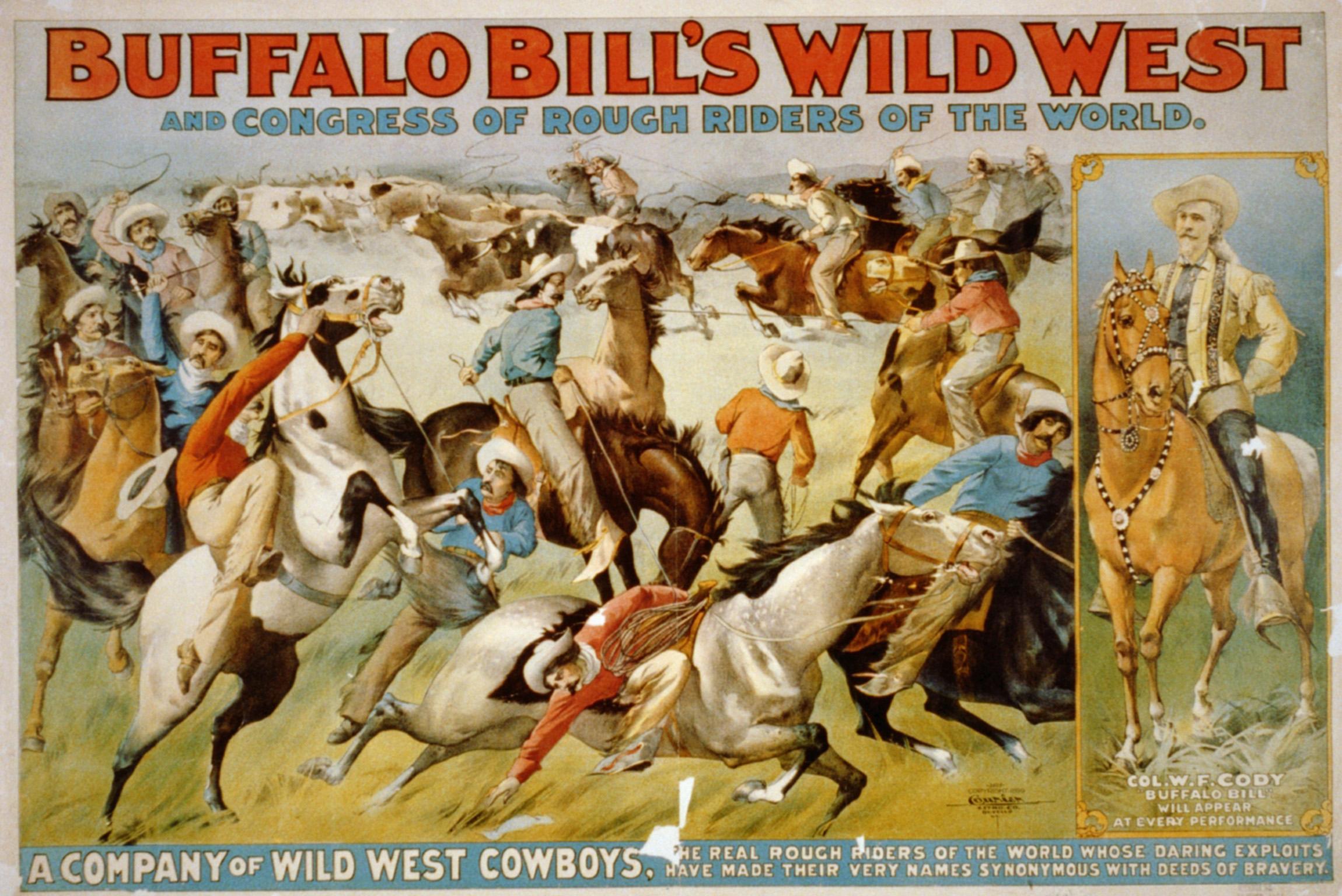

Your support makes all the difference.Throughout the 1880s, Buffalo Bill Cody dragged his new circus from town to town, improving the acts and recruiting new stars. But as it developed, the Wild West Show acquired a new form of success; it was no longer just a circus, no longer a troupe of acrobats performing on stage. No, it was something quite new: reality itself. Galloping horses, re-enacted battles, suspense, people falling down dead and getting up again: it had everything. And the audiences grew all the time: clapping, laughing, shouting, completely spellbound; as if the world had been created in a drum roll.

However, the real spark was elsewhere. The central aim of the Wild West Show was to astound the public with an intimation of suffering and death which would never lose its grip on them. They had to be presented with human figures shrieking and collapsing in pools of blood. There had to be consternation and terror, hope and a sort of clarity cast across life. And above all, there had to be a story, the story that millions of Americans, and then millions of Europeans, wanted to hear; the only story they wanted to hear, and the one that, perhaps without knowing it, they were already hearing in the crackle of the electric light bulbs.

They don’t want to hear them. They don’t want to talk to them. They just want to see them

The inhabitants of American cities – this new breed of humans whose disquiet is a stubborn question addressed only to them, who in the depths of their angst have a sense of being set apart, designated by the spirit of progress to seize the torch of humanity and hold it higher than anyone ever has before – they wanted to witness something different, they wanted to travel across the Great Plains in their imagination, to ride through the canyons of Colorado and experience the lives of the pioneers. But the thing that really made Buffalo Bill’s spectacle irresistible was the presence of the Indians, real Indians.

Of course they didn’t realise this themselves, because most of them despised Indians. But if they scrimped and saved to buy tickets for every member of the family, and took their seats quietly in a row on the “bleachers” (benches), it was unquestionably to see the Indians. So Buffalo Bill had to show Indians. And if such a spectacle was to prosper, he had to keep coming up with new stars. For this, apart from Buffalo Bill himself, there was his impresario Major John Burke.

Like most people who wore cuffs in those days, John Burke wasn’t a major at all. You come across him sometimes under the name of Arizona John, although he had never been to Arizona either. He was just a swindler of the worst kind. In those days, any nincompoop could found a city, become a general, a businessman, a governor or President of the United States; and perhaps this is still the case. John Burke had sensed the coming of the vast machinery of a culture of spectacle, and was now press officer to Buffalo Bill – his publicity agent, the greatest and the wackiest of them all. Thanks to a perfect match between the man and his times, the former journalist, broker and one-time leader of a troupe of acrobats became the inventor of show business.

Which was why, one morning in 1885, after several years of exile and imprisonment, the old Indian chief Sitting Bull, victor at the Battle of the Little Big Horn, received a visit from John Burke. The big beast had come alone, perched on a jolting sprung phaeton, following the narrow track that cut across a boundless plain. And although much tried by his journey, his manner was relaxed and affable.

He’d come with a mouth full of pieties, a few small presents and a clear blue sky. He offered a cigar to the Indian, who refused it. So he smoked his nabob’s peace pipe by himself, before the silent Indian and, after the usual greetings, during which a sly and ferocious battle was instantly engaged, Burke launched into a long, convoluted, labyrinthine and meandering speech. Between two compliments he rearranged his hair, pushing it back and clamping it round his ears. But the old Indian maintained an obstinate silence. And after a quarter of an hour of chatter, Burke realised that his hedging about was getting him nowhere; Sitting Bull seemed cagey, and he would do better to get to the point.

The Indian chief had long since known that the white man presented constantly changing faces and that he should not be taken in by any of them; they were all after something. To the panoply of those he already knew – trappers, soldiers, pioneers, cowboys, liquor sellers – he was now about to add that of impresario. But Sitting Bull already had a little showbiz experience; the previous year he had been exhibited among the waxwork figures of a museum in New York. So, once the flood of weasel words dried up, he negotiated $50 (£38) a week, plus an advance, all expenses to be covered by the impresario, and – above all, in a codicil that he insisted on adding – he would retain exclusive rights over the sale of photographs of himself along with the use of his autograph. Burke didn’t prolong the negotiations, because Sitting Bull was a choice attraction for the Wild West Show. So the contract was signed, and the Indian chief joined the troupe.

His first performance was a photographic pose. Sitting Bull and Buffalo Bill were escorted to a small booth where, with their feet on a carpet of straw, they had to stand in front of an emaciated birch tree daubed onto a canvas that supposedly depicted the untamed West. Sitting Bull looks somewhat ill at ease in this decor, like a misplaced remnant of the Creation. Suddenly no one moves, or barely, and for a few moments, during the morsel of time needed for the tiny motes of light to settle on the large chemical plate, Sitting Bull and Buffalo Bill shake hands. The photographer disappears behind his curtain, and Sitting Bull feels a profound solitude which thrusts him into that cold, godforsaken place where we stand rigid for as long as our relics last. In that moment, he forgets everything. He even forgets his dead brothers. The tepees, the fields, the encampments, the long journeys, he forgets it all.

The river bears away his memories in a roar of foam. But as the light shines through the clump of trees, it’s not just his stiff torso, his hardened, spare profile that is petrified like a great vessel of nostalgia. It’s as if there were something awaiting him in the photograph. He stands, at point-blank range, in the confusion of his selfhood, before the tiny leather accordion and the photographer’s black hood. Hold it! The bulb is raised, a hand squeezes. Through the small hole his soul looks out at him. Pop! It’s done. Sitting Bull and Buffalo Bill hold each other by the hand for all eternity. However, not only does this handshake mean nothing – it’s just a publicity stunt – but if it’s to be any use in the advertising campaign, the photo has to contain two contradictory messages: both the reconciliation between two peoples and the moral and physical superiority of the Americans. Which is why, in the photograph, Buffalo Bill exaggeratedly puffs out his chest in an attempt to give himself a more dignified air. He stands very straight, his left leg thrust slightly forward, his head held regally high, sizing up the Indian. Sitting Bull stares into the void, and simply extends his hand. Progress wins out. We look on with perplexity.

Not for one moment did anyone think to get him to perform an episode from the Indian wars or from some other time his life

I don’t know exactly where in the United States Sitting Bull made his first stage appearance, but the show never changed very much. Right at the beginning, while “The Star- Spangled Banner” is being played, Buffalo Bill suddenly appears: he’s on horseback, his arm is raised, and he holds his hat in his hand. Cowboys and Indians parade around him, also on horseback. A trumpet sounds. And then, the person everyone has been waiting for enters the arena. For the highlight of the show isn’t a show, it’s reality. And now it’s starting. An Indian enters the arena; it’s the victor of the Battle of the Little Big Horn. He’s wearing his finest costume. “Ladies and gentlemen, let me introduce the great Indian chief…” vociferates the announcer Frank Richmond from his rostrum.

Sitting Bull has probably never been as alone as he is at this moment, in the midst of the American flags and the great entertainment machine. He wasn’t as alone as this when he was living in exile in Canada, with a bunch of other undesirables; the initial darkness is impenetrable. And to be sure, you would be alone on horseback, in the icy rain, wandering between indistinct shapes in the great forest. Yes, you would be alone and sad, but you were free, and you were filled with a burning hatred. And now Sitting Bull is alone in the arena; the grand thing that he loved has been left behind, a long way behind. And here, on the bleachers, this is what people have come for; they’ve all come to see this, and only this: his solitude.

This is when the booing and the catcalls start to fly. Sitting Bull remains impassive, he does his lap of the arena. Not for one moment did anyone think to get him to perform an episode from the Indian wars or from some other time his life: a simple parade would suffice. There is no scope for history. The past is surrounded by bleachers, and the spectators want to see its ghosts. But nothing else. They don’t want to hear them. They don’t want to talk to them. They just want to see them. They want to draw back the curtain for a moment and see the Indian.

But what do we see? What do we hear? What is this voice that speaks? The crowd roars and shouts abuse at him. The people spit. There it is, the unprecedented thing, the Red Indian we came to see, the strange beast that prowled around our farmsteads, or so they say. “That’s him!” From the wings Buffalo Bill signs to Frank Richmond who tries to quiet the spectators. But it’s no use, the Indian chief will have to complete his lap under the hail of abuse, until he reaches the end. The hubbub is extraordinary. The journalists take photographs. Children stare wide-eyed. Sitting Bull slowly leaves the arena.

But who was Buffalo Bill, the creator and star presenter of the show? It’s said that he had the build of a lumberjack and the hands of an artist, very delicate hands that were almost too fine, which – as we are informed by the mysteries of science – indicates a predisposition to insanity. And indeed, throughout his life Buffalo Bill would have moments of deep despair, bouts of serious depression. Although he raked in potloads of dollars and salvos of applause, as soon as the curtain fell he would find himself alone once more. And no sooner had he removed his make-up in his old entertainer’s lair, than he felt a horrible anguish. In front of the mirror, while he mechanically combed his hair after removing his Stetson for the thousandth time, he would feel a terrible pang in the chest – as if his entire being was a void.

At that time, Buffalo Bill’s body was already a pure product of marketing, a sort of sham. Nobody knows what lay behind the orgy of publicity. And it’s even harder to know what the showbiz entrepreneur, the superstar he had become, actually thought about. He wasn’t one of those people who leaves no trace; but excess is a different kind of problem from insufficiency, and if archaeology is the science of remains, there exists no branch of research devoted to things that have been exposed too much to sight.

The strangest part of the whole business is the most banal. Buffalo Bill performed the same meaningless scenes over and over again, sticking to the same routines, with the same gusto. Success is a form of vertigo. Repetition must have some reassuring property, some power of hypnosis or truth. As the hero of numerous fanzines, whose existence he was initially unaware of, his life was fashioned by others. He decided neither his name nor his story. Around 1867, when he was working for the railways, the labourers gave him the nickname of Buffalo Bill. Then, by pure chance, between two shots of liquor, he told the tale of his adventures to one Ned Buntline who made a dime novel out of them. And the hoodlum’s yarn, all blarney, asseveration and fabrication designed to earn him another drink, had become the stuff of serialised fiction.

As one episode followed another, the character of Buffalo Bill, a mix of a night’s bragging and the numerous extensions, suffixes and increments added by Buntline with every page, had acquired a sort of celebrity. Later on, Buffalo Bill would learn that an actor, Jason Ward, was playing the part of himself on the stage and that his character had become famous. So nothing had been decided by him. His life escapes him. A great counterfeiting force had sucked him in, replicated him and produced a revised version. In the end, he was induced to play the part of himself. This is how he came to mount the boards, wearing fancy dress, simply to match his own character. He’s an imitation of himself. He gradually became the person he was portraying. His life would become a sort of parody of his life, an alternative, fabricated life, pledged to others. The illusion was so powerful, the public so thoroughly won over, that the actors in the show, who had never set foot in the West and never fired anything but blanks, apparently ended up believing the hogwash they narrated, and the adventures they mimed.

And so it’s said that, at the end of his life, after performing the Battle of Little Big Horn dozens of times over, Buffalo Bill genuinely believed that he had taken part in it. To meet the requirements of the show, they had even gone so far as to change the outcome, because audiences prefer a happy ending. Which is how, after years spent successfully performing this amended version of grand history, Buffalo Bill was convinced that he had saved Custer! But real life is still there. It returns to us with each drop of rain, in the fragile mystery of things. I imagine him sleeping in all kinds of hotels, or in his special train, with its saloon, its billiard table, kitchens and bathrooms, Buffalo Bill will be sipping a drink, as large clouds darken his carriage. For a moment, he leans out of the window, and senses the huge locomotive, way out in front, very tall and completely black.

As the wind slaps his face, he hears the frightful rumbling of the engine. Turning his head, he sees broad, uncultivated expanses, yellow grasses, the remains of a forest bristling with dead pines. He sits down again, his eyes roasted by the smoke. He thinks about all the people who come and go, the people he hires and then fires, as if he were dipping his hand in and out of a bag of salt. And while his fingers hover among the crumbs on the table, amid the worries of the entrepreneur, the last-minute problems he has not yet solved, there rises an obscure sense of remorse.

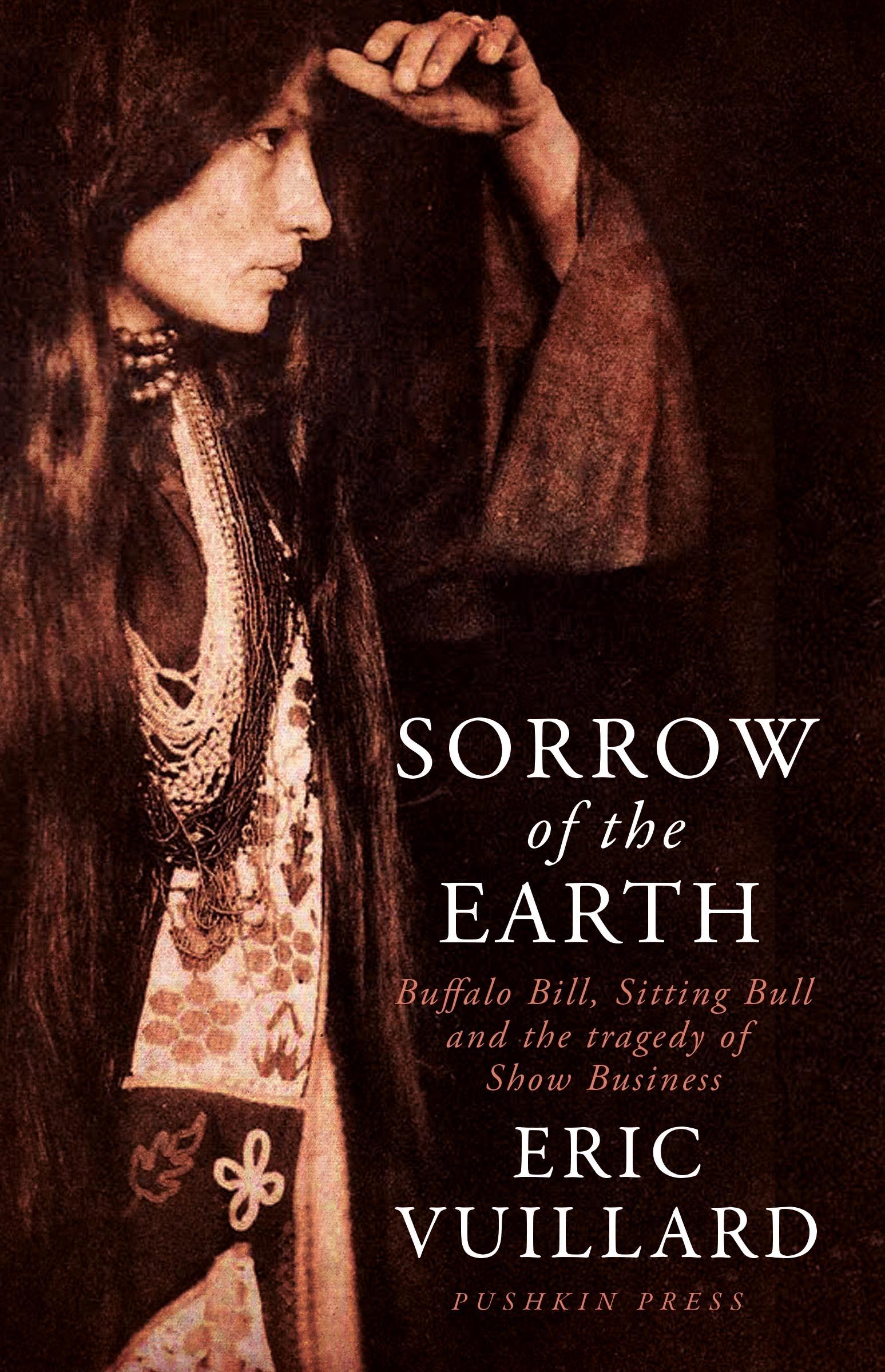

This is an edited extract from ‘Sorrow of the Earth: Buffalo Bill, Sitting Bull and the Tragedy of Show Business’, by Eric Vuillard and translated from the French by Ann Jefferson (Pushkin Press, £12.99), published on 15 September

Pushkin Press is offering a special pre-publication price of £10, available at http://pushkinpress.com/book/sorrow-of-the-earth, until 15 September

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments