Hassan Akkad: ‘Losing the only circle of support you’ve ever known is devastating’

When you’ve been face to face with President Assad and told him he should be toppled for killing his own people, calling out Boris Johnson over his treatment of NHS workers is relative child’s play. Rory Sullivan talks to the Syrian refugee who became a filmmaker, hospital cleaner, activist – and now published author

Along with dozens of other Syrians, Hassan Akkad was crammed onto a small rubber dinghy heading from Turkey to Europe in the summer of 2015. Weighed down by so many bodies, it started to take on water and, for a time, tragedy looked inevitable, until a Turkish ship sailed into view.

Onboard the deflating vessel were people from most cities in the war-torn country; individuals huddled together from all walks of life, university professors and belly dancers alike. Nine children and a pregnant woman were also packed in like sardines. Akkad says he had not met such a diverse group of Syrians since being holed up four years earlier in a prison cell run by the nation’s notorious intelligence agency, the mukhabarat. “I really felt like Syria itself was on that boat and it broke my heart,” he recalls in his memoir, Hope Not Fear, published this week.

As the boat started to sink, Akkad, then in his late twenties, was among those who jumped off to reduce the load. He recorded the desperate scenes on his GoPro, with the footage later broadcast to thousands via the BBC documentary series Exodus: Our Journey to Europe, which looked at migration through the eyes of those who had, like him, fled their homes and undertaken perilous journeys in search of safety and security.

For Akkad, the attempted crossing was the grimmest part of a gruelling three months which saw him travel from Turkey to Britain. Accompanied by two friends, Alaa and Aghiad, he made his way via people smugglers, including the Serbian mafia who whisked them through Hungary, and via advice given on migrant Facebook groups. Filming their progress was a means for Akkad to distance himself from their frightening predicament. “It made me feel like a film director rather than an asylum seeker. It isolated me from the situation; the camera protected me,” he explains.

After a seemingly interminable stretch in northern France, he eventually wound up in London, flying in from Brussels on a fake Bulgarian passport. In the five years since his arrival, Akkad has been busy forging a new life and making a name for himself as an activist and filmmaker, driven to counter the rising tide of anti-immigration in the UK.

“I think most of the time people who are anti-immigration haven’t met or had dinner with a migrant,” he tells me over orange juice and chips in King’s Cross. Akkad adds that, time and time again, strangers have been surprised to learn his backstory – no doubt thrown by his impeccable English and impressed by his strengths as a communicator. “But you’re normal,” they say, a response he blames on how migrants and refugees are often reduced to statistics or personality-less “victims in tents or in boats”.

Looking back at his youth, he admits he was not overly welcoming himself to Middle Eastern refugees who settled in his home city of Damascus. Much, of course, has changed for Akkad since then and his world view has shifted significantly, altered by self-education and his country’s civil war.

The former English teacher’s public success in Britain started with victory for Exodus at the Bafta awards, where he gave one of the acceptance speeches. There followed other unexpected turns, including a close friendship with actor Emma Watson and a speaking tour around the world. In his own words, he was catapulted into becoming “the poster boy of the refugee crisis”, not long after arriving in England with little except “what was inside” his head.

A few years later, he returned to the public spotlight in a political capacity, using his storytelling ability to affect change. While working as a cleaner at his local NHS hospital during the pandemic, he saw up close how much the health service relied on migrants such as his friends Albert and Gimba, who are from Ghana and Nigeria. When the government revealed in May last year that workers in their roles would not be included in its Covid-19 bereavement scheme for frontline staff, he was incensed and decided to film a short message addressed to Boris Johnson.

From his car outside Whipps Cross Hospital, he thanked the prime minister for starting a weekly clap for NHS staff. His voice quivering with emotion, he then launched into a rebuke that went viral: “Today, however, I felt betrayed, stabbed in the back. I felt shocked to find out you’ve decided to exclude myself and my colleagues, who work as cleaners and porters and social care workers, from the bereavement scheme. This is your way of saying thank you?”

Akkad ended the video by asking the Tory leader to reconsider the decision, which the government duly did in one of its many coronavirus U-turns. Reflecting on the past year and a half, he says it is only natural that people in power make mistakes during times of crises, but claims that “the scale of the failure here was a lot higher than any other country”.

This moment last May was the first time he had felt confident to speak his mind publicly in his adopted country. “I was genuinely still scared. I wasn’t aware of the rules. What if you say something or go on a protest? Can they cancel my refugee status? You ask yourself these questions. I wanted to live a peaceful life, going through what I had gone through,” he tells me.

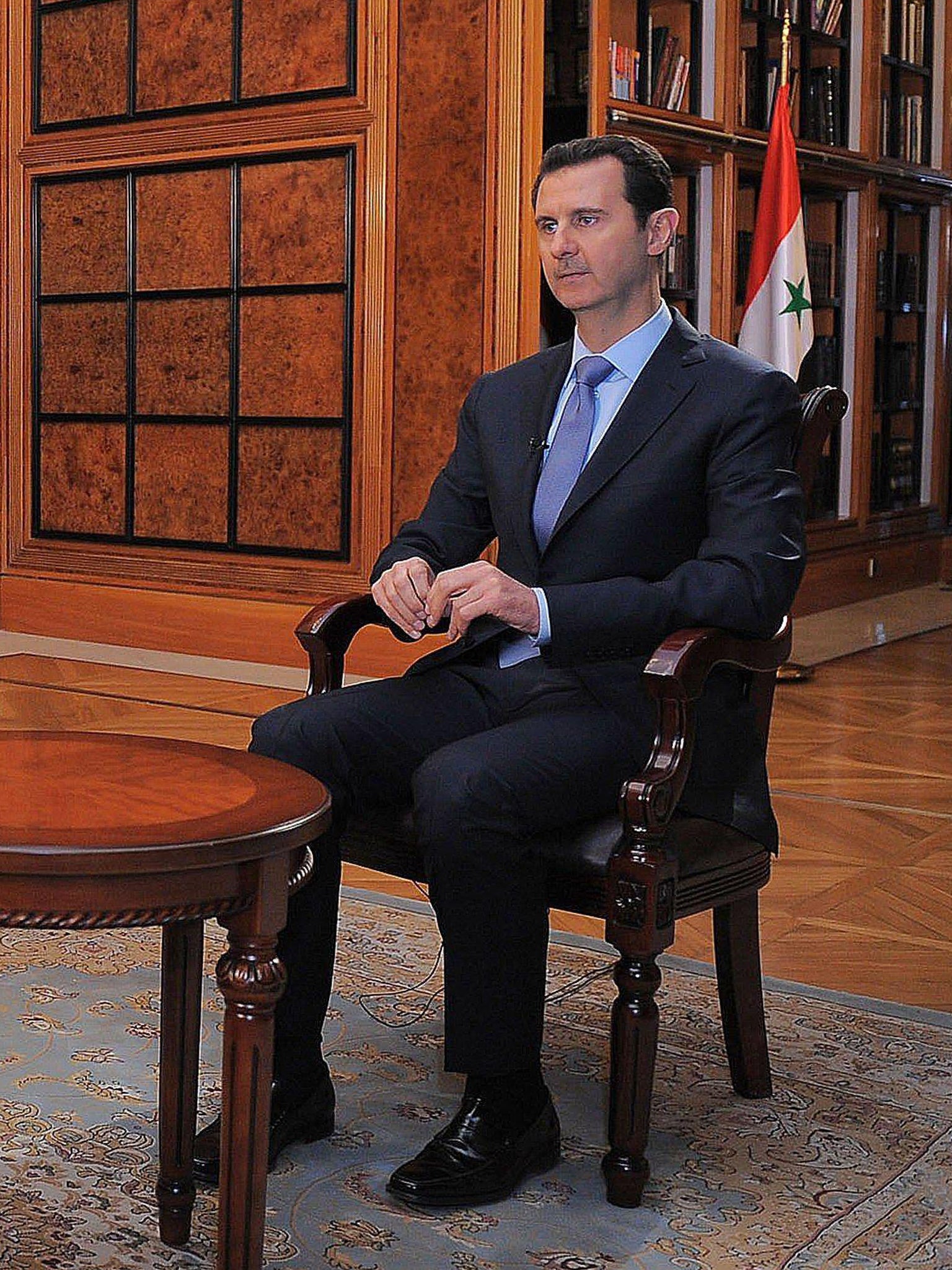

Back in Syria, he had risked much more by speaking out against injustice. Like many others, he joined the wave of popular protest against the brutality of Bashar al-Assad’s regime, before being detained, severely beaten and carted off to prison from an anti-government rally. With two broken arms and an infected leg, he was in a bad way when he was freed through the connections of his cousin Majd, who shortly afterwards invited him to a group discussion at the president palace.

In perhaps the most remarkable and surreal scene from his book, he recounts the conversation he had with Assad during this meeting. Not wanting to gloss over the torture the security services were inflicting on civilians behind closed doors, the then 23-year-old spoke his mind, telling the dictator that he wanted him to be toppled. “Assad is akin to a god because he’s on every poster, in every textbook, every news bulletin. So the fact that I told him he was doomed to fall one day for killing his own people is something that I’m proud of. I don’t regret it, but I think it led to my second detention, which was very bleak.” (In this subsequent incarceration, Akkad was sexually abused and became so depressed he took an overdose in an attempt to end his life.)

Pain still stalks him. Due to the trauma he has experienced, he suffers from PTSD and is currently receiving treatment for the condition. His separation from his family, who are living in the UAE and Iraq, is a source of constant hurt and has changed him forever, he says. “It’s the worst thing that could ever happen to anyone. It doesn’t hit you instantly and it’s gone. Losing the only circle of support you’ve ever known is devastating.” He is fully aware of just how many millions of other Syrians endure similar agony. As he writes at various points in Hope Not Fear, his story – the account of just one individual – “stands for so many Syrians”.

Ahmad Al-Rashid, whose migration story also appears in Exodus, is another person whose life was upturned by the Syrian civil war. After first fleeing to Iraq, he decided to risk the journey to Europe when Isis overran the area where he was staying. He now works for the International Organisation for Migration (IOM) and lives with his family in the Midlands, after first completing a masters in violence, conflict and development studies at Soas.

Like Akkad, he was already fluent in English, which prompted him to aim for the UK and made it much easier for him to settle once he arrived. But the journey was hazardous, including the worrying time he spent stowed away on an poorly ventilated lorry in France, an experience he describes as “basically meeting your own death”. He did not set out to make the footage he captured public, but simply recorded it for his family. “I always intended for it to be private. I said to my wife, ‘Look, if I die or something happens to me, show it to our children, saying that I’ve done everything I could but unfortunately things didn’t work out.’”

Both Syrian men acknowledge their route across the continent is now almost impossible for people in similar positions to them. “Europe in 2015 is different from Europe in 2021. You’ve now got more border controls, you’ve unfortunately got more anti-refugee rhetoric, more restrictions on movement,” Al-Rashid says.

In the UK, anti-migration voices grew louder earlier this summer after a rise in the number of asylum seekers crossing from France to the Kent coast by dinghy. The subject of immigration is also back in the headlines due to the Taliban’s swift power grab in Afghanistan. Responding to the growing humanitarian crisis there, the UK government pledged to accommodate 20,000 Afghan refugees over the next five years, in a scheme the Home Office says is modelled on the Syrian Resettlement Programme.

Critics, however, have said this number is too low and that the initiative needs to operate faster than currently planned. Akkad is among those who believe the British government is not doing enough. Speaking about the earlier resettlement of 20,000 Syrians, he says the total is “shameful to be honest”. He adds that other countries accept far more asylum seekers with fewer complaints than British ministers. “Turkey took 4 million Syrians, and the Turkish government genuinely doesn’t complain about refugees as much as the British government.”

The 33-year-old contrasts the cabinet’s reluctant approach to the work of organisations like Refugees at Home, a charity which provides new arrivals with a roof over their heads. Before co-founding the NGO in 2015, Sara Nathan knew the good such a service could do, as her parents had hosted children who fled the Nazis on the Kindertransport. “We knew that hosting was a response to this sort of need. That at a time when you couldn’t spend three months in Calais or go out to Lesbos, you could combine hosting with your own life.”

Five years on, the charity has provided 2,500 refugees with accommodation, for spells lasting from several days to several years. Al-Rashid was one of the first to find a room through Refugees at Home, after he received refugee status and had 28 days to leave government accommodation. “The thought of being homeless at that time was a terrifying prospect. I didn’t know anyone at that point. I had no money, no contacts, no references or anything like that. It was a very difficult time and I didn’t know what to do,” he recalls.

Al-Rashid put a message out on social media and was connected with a host family in Epsom. Initially, he took the bus down from Middlesbrough to Surrey, expecting to stay for only a brief while. However, he lived there for almost five months, saying he learned a lot about British culture during the period.

“I find most of the British public really caring. They want to help,” says Akkad, who also benefitted from a host who provided him with a room in Hitchin, Hertfordshire, for three months. This allowed him time to settle and to start rebuilding his life.

Nathan holds a similarly optimistic view about the British public. Referring to the Afghanistan resettlement scheme, she says: “It seems to me that we can do much better than that, as an open and welcoming society.”

“We take remarkably few people compared to most of Europe and certainly very, very few compared to countries in war-struck areas. Location should not be a reason not to step up to our humanitarian responsibilities,” she adds.

Meanwhile, the Home Office insists it is being fair in its response to the situation in Afghanistan. “We will welcome 5,000 Afghans in year one, with an ambition of resettling up to 20,000 in the long term if needed. This is a sustainable intake, in line with most of our international partners,” a government spokesperson tells The Independent.

Like Nathan, Cherno Jagne, chief operating officer of Choose Love, a refugee NGO which works in 15 countries, thinks the UK government should help more vulnerable people. He also believes that Britain must reduce the hurdles facing those who do arrive.

“It’s a hostile environment for many refugees when they arrive in the UK. It’s tough. Many of them suffer from severe destitution, severe mental health crises,” he says, adding that some asylum-seekers get lost in the system, unable to work while their claims are being processed and surviving off a government grant of just £5.64 a day.

Laying out a more hopeful vision, Jagne points to Akkad, who is an ambassador at Choose Love, as a shining example of “how opening our borders can be beneficial to society”.

Hope is something which accompanied both Al-Rashid and Akkad on their journeys. Six years on, the former says he headed to Europe for the sake of his children. “It was worth it – the dangers, the difficulties, the risk. You see them growing up in a safe place – physically, mentally, emotionally, academically,” he says.

For Akkad, the white cliffs of Dover, which were visible from a makeshift camp in northern France, represented the hope of stability. As part of a project organised last year by the campaign group Led By Donkeys, a video showing Akkad, who is keen to go into politics, was projected onto a segment of the rock. After rubbishing the notion that Britain faced a “refugee crisis”, he addressed the British public with a simple message: “The only difference between you and us is luck. Just like you, we want what is best for us and our families.”

Hassan Akkad’s memoir ‘Hope Not Fear’ is published by Bluebird and can be ordered here

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments