A Life in Focus: Ian Smith – last white leader of Rhodesia, now Zimbabwe, who fought to preserve minority rule

The Independent revisits the life of a notable figure. This week, from Thursday 22 November 2007, Rhodesian prime minister Ian Smith

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When the final history of the decolonisation of Africa is written, Ian Smith will merit little more than a footnote. He will be remembered as a small-minded Canute who tried to resist the tide of black rule sweeping inexorably across the continent. Had he never existed, the history of the middling-sized, stunningly beautiful country now called Zimbabwe but once known as Southern Rhodesia, and under Smith as plain Rhodesia, might have been much the same.

But to dismiss Ian Smith out of hand would be to forget how for some 15 years, his country held international diplomacy and British domestic politics to ransom, and how Smith himself, author of Rhodesia’s Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI) and prime minister of the last but one white supremacist regime in southern Africa, was once a household name around the world.

Smith’s background was quintessentially colonial. His father, Jock Smith, had emigrated from Scotland to Rhodesia in 1898, on the eve of the Boer war, and settled at the small rural town of Selukwe, now called Shurugwi. There he ran a farm and a mine, bred racehorses, and chaired the local rugby and cricket clubs.

The young Ian, born in 1919, inherited Jock’s energy and resilience. He was an undistinguished student, but like his father (and most Rhodesians, for that matter) a passionate sportsman and lover of outdoor life.

When war came in 1939, nothing was more natural for an adventurous and patriotic young man than to share in the defence of the British Empire. Smith enrolled for training as a pilot, and his war took him from Africa to Persia, the Middle East and Europe first with 237 (Rhodesia) Squadron and then 130 Squadron of the RAF. He was shot down in a Spitfire over Corsica, and for five months fought alongside Italian partisans behind German lines.

Decades later, this war service would further complicate attitudes to Smith, now rebel and foe, but who had done more than his bit to save Britain from Hitler.

He described himself as an “African of British stock”. But in many respects, Rhodesians were more British than the British. The cultural overlaps meant many Britons of a certain generation simply could not understand why “Good Old Smithy” and “Plucky Little Rhodesia” were held in such official disapproval.

Smith’s first priority on returning home was to finish his degree course at Rhodes University in Grahamstown, South Africa. But politics soon beckoned. In 1948, he was persuaded to stand for parliament for the Liberal Party, and in a momentous August that year he bought a farm, won his first election, and gained a wife, his beloved Janet. She would give him three children and an anchor amid the turbulence of the struggle over Rhodesian independence.

By then the country was a self-governing colony, but pressure was growing for full nationhood. For eight years, between 1953 and 1961, the chosen solution was the Central African Federation – a loose white-run union of Nyasaland (now Malawi), Northern Rhodesia (today’s Zambia), and Southern Rhodesia – conceived as a vehicle to full independence. But by 1960 the federation was falling apart. In Nyasaland and Northern Rhodesia, pressures for secession and black rule were growing. In Britain, attitudes were shifting. Harold MacMillan spoke of the “winds of change” blowing through Africa, and Britain’s vital ally, the United States, was pressing for decolonisation.

Southern Rhodesia’s white minority, however, would not comply. The federation broke up, and in Salisbury a new white nationalist party, the Rhodesian Front, won power. Smith was its deputy leader and was named deputy prime minister in the new government under Winston Field. But Field was too moderate for the Front. Impatient for an early declaration of independence, his parliamentary party voted him out of power and Smith took over. The “African of British stock” was in power. Six months later, in Britain’s general election, Harold Wilson’s Labour Party defeated the Conservatives. The stage was set for a showdown between the colonial power committed to black majority rule, and the white settlers who had taken over an African land.

Old white Rhodesia, the joke ran, was a “Surrey with the lunatic fringe on top”. Whether it was lunatic was a matter of opinion. But suburban Surrey it did resemble in its parochiality, its golf-club outlook on the world, its unquestioning certainty in its own values. The white population never exceeded 120,000, 3 per cent of the total and no more than a decent English provincial town, but they believed they had created God’s Own Country.

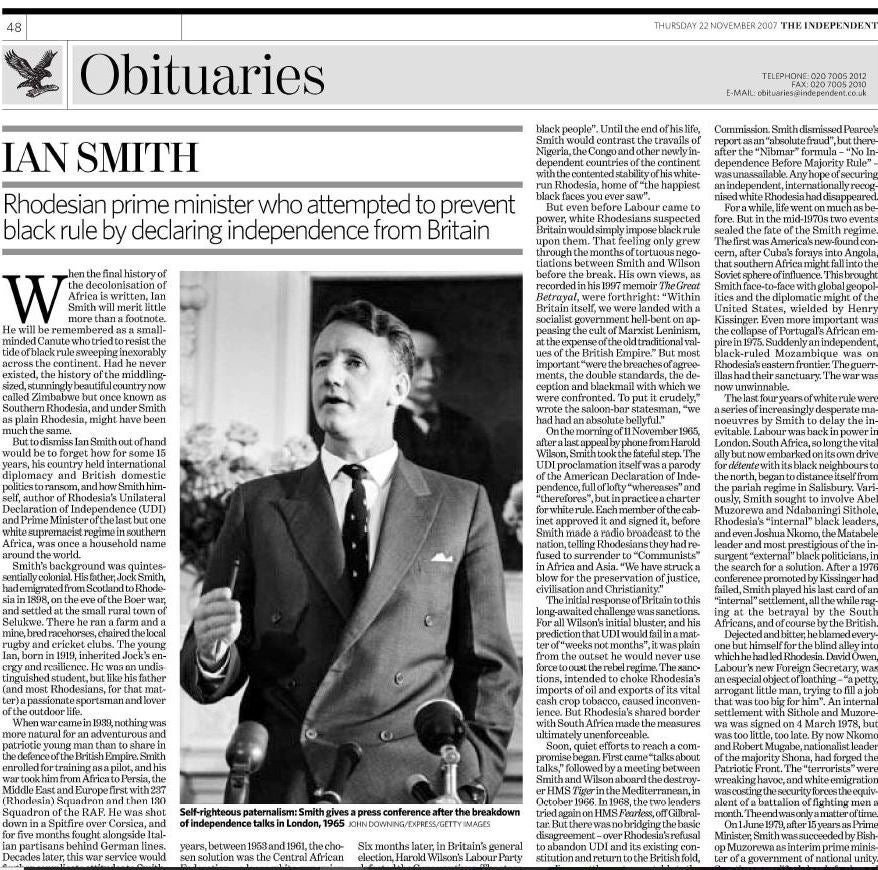

White rule in Southern Rhodesia, at least until the liberation war began in earnest in the late 1960s, was subtly different from its counterpart in South Africa. The end product might have been the same, but it was underpinned less by brutality than by self-righteous paternalism. Whites referred without a trace of self-consciousness to “our black people”. Until the end of his life, Smith would contrast the travails of Nigeria, the Congo and other newly independent countries of the continent with the contented stability of his white-run Rhodesia, home of “the happiest black faces you ever saw”.

But even before Labour came to power, white Rhodesians suspected Britain would simply impose black rule upon them. That feeling only grew through the months of tortuous negotiations between Smith and Wilson before the break. His own views, as recorded in his 1997 memoir The Great Betrayal, were forthright: “Within Britain itself, we were landed with a socialist government hell-bent on appeasing the cult of Marxist Leninism, at the expense of the old traditional values of the British Empire.” But most important “were the breaches of agreements, the double standards, the deception and blackmail with which we were confronted. To put it crudely,” wrote the saloon-bar statesman, “we had had an absolute bellyful.”

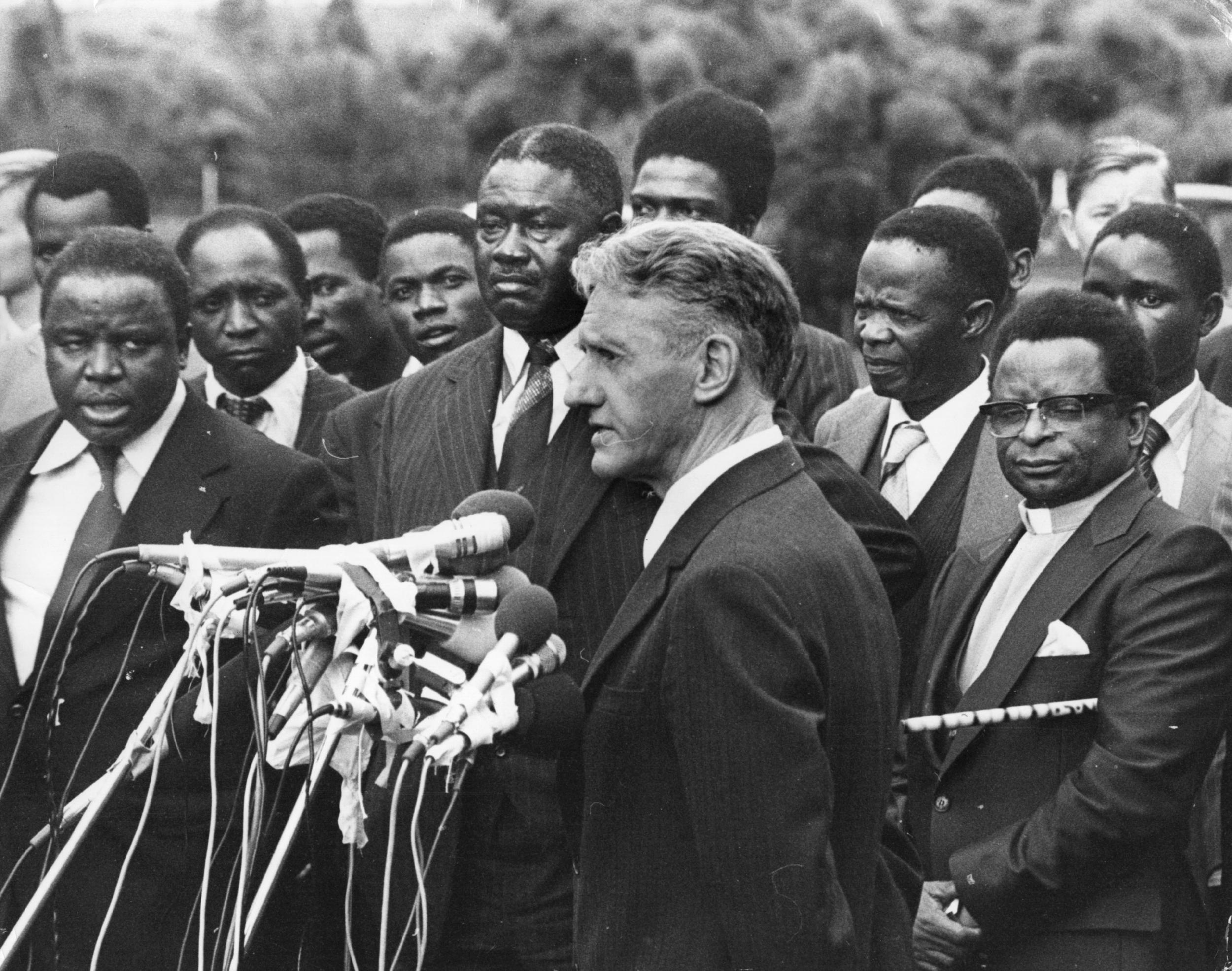

On the morning of 11 November 1965, after a last appeal by phone from Harold Wilson, Smith took the fateful step. The UDI proclamation itself was a parody of the American Declaration of Independence, full of lofty “whereases” and “therefores”, but in practice a charter for white rule. Each member of the cabinet approved it and signed it, before Smith made a radio broadcast to the nation, telling Rhodesians they had refused to surrender to “communists” in Africa and Asia. “We have struck a blow for the preservation of justice, civilisation and Christianity,” he declared.

The initial response of Britain to this long-awaited challenge was sanctions. For all Wilson’s initial bluster, and his prediction that UDI would fail in a matter of “weeks not months”, it was plain from the outset he would never use force to oust the rebel regime. The sanctions, intended to choke Rhodesia’s imports of oil and exports of its vital cash crop tobacco, caused inconvenience. But Rhodesia’s shared border with South Africa made the measures ultimately unenforceable.

Soon, quiet efforts to reach a compromise began. First came “talks about talks”, followed by a meeting between Smith and Wilson aboard the destroyer HMS Tiger in the Mediterranean, in October 1966. In 1968, the two leaders tried again on HMS Fearless, off Gibraltar. But there was no bridging the basic disagreement – over Rhodesia’s refusal to abandon UDI and its existing constitution and return to the British fold, pending a settlement acceptable to the black majority.

The next half dozen years were the apogee of Good Old Smithy’s Rhodesia. In Britain, the proprietors and leader writers of Conservative newspapers loved him, and soon a more sympathetic Tory government won power. Sanctions by now were little more than a joke, guerrilla activities were comfortably contained by the Rhodesian security forces, and any domestic white opposition was mostly silenced by the house arrest of the former prime minister Garfield Todd in 1972, and the exile of his daughter Judith.

But there was one ominous setback – though it did not seem so at the time. In 1971, Smith struck a deal with the Conservative Foreign Secretary Alec Douglas-Home that would have legalised UDI in return for a new constitution pushing black rule into the remotest of futures. The agreement, however, was massively rejected when the African population was consulted by the Pearce Commission. Smith dismissed Pearce’s report as an “absolute fraud”, but thereafter the “Nibmar” formula – “No Independence Before Majority Rule” – was unassailable. Any hope of securing an independent, internationally recognised white Rhodesia had disappeared.

For a while, life went on much as before. But in the mid-1970s two events sealed the fate of the Smith regime. The first was America’s new-found concern, after Cuba’s forays into Angola, that southern Africa might fall into the Soviet sphere of influence. This brought Smith face-to-face with global geopolitics and the diplomatic might of the United States, wielded by Henry Kissinger. Even more important was the collapse of Portugal’s African empire in 1975. Suddenly an independent, black-ruled Mozambique was on Rhodesia’s eastern frontier. The guerrillas had their sanctuary. The war was now unwinnable.

The last four years of white rule were a series of increasingly desperate manoeuvres by Smith to delay the inevitable. Labour was back in power in London. South Africa, so long the vital ally but now embarked on its own drive for détente with its black neighbours to the north, began to distance itself from the pariah regime in Salisbury. Variously, Smith sought to involve Abel Muzorewa and Ndabaningi Sithole, Rhodesia’s “internal” black leaders, and even Joshua Nkomo, the Matabele leader and most prestigious of the insurgent “external” black politicians, in the search for a solution. After a 1976 conference promoted by Kissinger had failed, Smith played his last card of an “internal” settlement, all the while raging at the betrayal by the South Africans, and of course by the British.

Dejected and bitter, he blamed everyone but himself for the blind alley into which he had led Rhodesia. David Owen, Labour’s new foreign secretary, was an especial object of loathing – “a petty, arrogant little man, trying to fill a job that was too big for him”. An internal settlement with Sithole and Muzorewa was signed on 4 March 1978, but was too little, too late. By now Nkomo and Robert Mugabe, nationalist leader of the majority Shona, had forged the Patriotic Front. The “terrorists” were wreaking havoc, and white emigration was costing the security forces the equivalent of a battalion of fighting men a month. The end was only a matter of time.

On 1 June 1979, after 15 years as prime minister, Smith was succeeded by Bishop Muzorewa as interim prime minister of a government of national unity. Sanctions were lifted ahead of a planned all-party conference at Lancaster House in London, chaired by the new Tory foreign secretary, the worldly and urbane Peter Carrington – for Smith the embodiment of Perfidious Albion.

Skilfully, Carrington converted Margaret Thatcher – who instinctively shared Smith’s view that Mugabe and Nkomo were terrorists – to the belief they had to be part of any settlement. Thus, even the Tories jettisoned their Rhodesian kith and kin. The Lancaster House agreement was duly signed, ending the guerrilla war and providing for all-party elections, to be held in March. As expected by Smith and feared by the British, the result was a landslide victory for Mugabe.

To his amazement, Smith wrote later in his memoirs, his first meeting with a man he regarded as a hardline Marxist revolutionary revealed Mugabe to be someone who “behaved like a balanced, civilised westerner, the antithesis of the communist gangster I had expected”. For a while there was an uneasy coexistence as the neophyte prime minister occasionally consulted with the crusty leader of the white opposition in parliament. But all semblance of a truce was destroyed the following year when Mugabe made clear his intention of creating a one-party state. After July 1981, the two never met at length again. Smith remained in politics, head of the Conservative Alliance of Zimbabwe, as the Rhodesia Front was renamed. His true role, however, was as self-appointed Cassandra, for whom the steady decline of his country produced an unbroken refrain of “I told you so”.

But unlike many whites, demoralised by Mugabe’s constant attacks, Smith did not leave the country. After he left active politics, he divided his time between his 5,000-acre farm in central Zimbabwe and Harare, where he lived in a modest bungalow – close, as it happened, to the Cuban embassy, last outpost of those communist regimes to which he attributed Zimbabwe’s and Africa’s ills.

In 1994 his wife Janet died, but Ian Smith still remained in the public eye. Three years later, he published his memoirs, and until the end continued to denounce the iniquities of the Mugabe government, its corruption, greed and incompetence, and in particular its plan to take back the white farms – a step, in Smith’s view, that would inflict further damage upon the traditional support of Zimbabwe’s economy, and thus depress the standard of living of the black people whose interests Mugabe purported to have at heart. In that prediction he was tragically correct.

By the end Smith had mellowed somewhat, but at heart he was as stubborn and humourless as ever. He still wore his old Spitfire pilot’s tie and blamed his fall on everyone but himself. He still denounced the folly of appeasing totalitarians of whatever creed or colour, and stayed true to his receding vision of the vanished Rhodesian paradise. The clock of course could not go back. Salisbury had long since become Harare, and Cecil Square was renamed in honour of the Organisation of African Unity. By the end of Smith’s life, the old enemy communism was to all intents and purposes no more, and there were more elephants than whites in Zimbabwe.

The depredations of Mugabe ensured Smith had a point. You did not have to be an unreconstructed white supremacist to lament the collapse of Zimbabwe, as Mugabe the revolutionary turned into a brutal, lunatic totalitarian, who exacted a terrible price from a country which at independence seemed to have everything: international goodwill, a decent social infrastructure, and relatively advanced industry and agriculture.

“We had the highest standard of health and education and housing for our black people of any country in Africa,” he would claim. “That was what Rhodesians did, and shouldn’t we be given credit for doing that?” But Mugabe’s tyranny – as was Smith’s own feat in stopping history’s clock for 15 years – was just another facet of a continent’s tragedy.

Ian Douglas Smith, Rhodesian prime minister, born 8 April 1919, died 20 November 2007

Rupert Cornwell died in 2017

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments