Rupert Cornwell obituary: Award-winning foreign correspondent who embodied the spirit of The Independent

Rupert was a foreign correspondent for four decades and was among The Independent's original staff

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Rupert Cornwell was one of the great foreign correspondents of our time. He embodied the very spirit of the newly launched Independent in 1986, and he remained one of its the wisest and most eloquent voices until his death at the weekend, aged 71.

He spent much of the past 26 years living in and reporting on the United States. This era included 9/11, and spanned the presidencies of George Bush Sr, Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, Barack Obama and now, Donald Trump. One of his final published stories, just a few weeks ago, was on Ivanka, “the most powerful first daughter in US history”.

But the story that brought him to The Independent, and the story that first brought him acclaim, was Russia. Stephen Glover, the paper’s co-founder and first foreign editor, approached him in the spring of 1986, initially with an offer to become the yet-to-be-launched paper’s Paris correspondent. Rupert was Bonn correspondent for the Financial Times, then as now one of the most respected papers in the world.

For security and job-satisfaction reasons alike, FT journalists were not easily tempted away. But Moscow proved to be the lure: Rupert agreed to throw his lot in with this risky new project if he could be posted to Moscow instead of Paris. The Independent agreed, and the rest was history.

The timing was perfect. Mikhail Gorbachev’s perestroika and glasnost – the twin policies of economic change and greater political openness that were unfolding at that time – were a story of fascination worldwide.

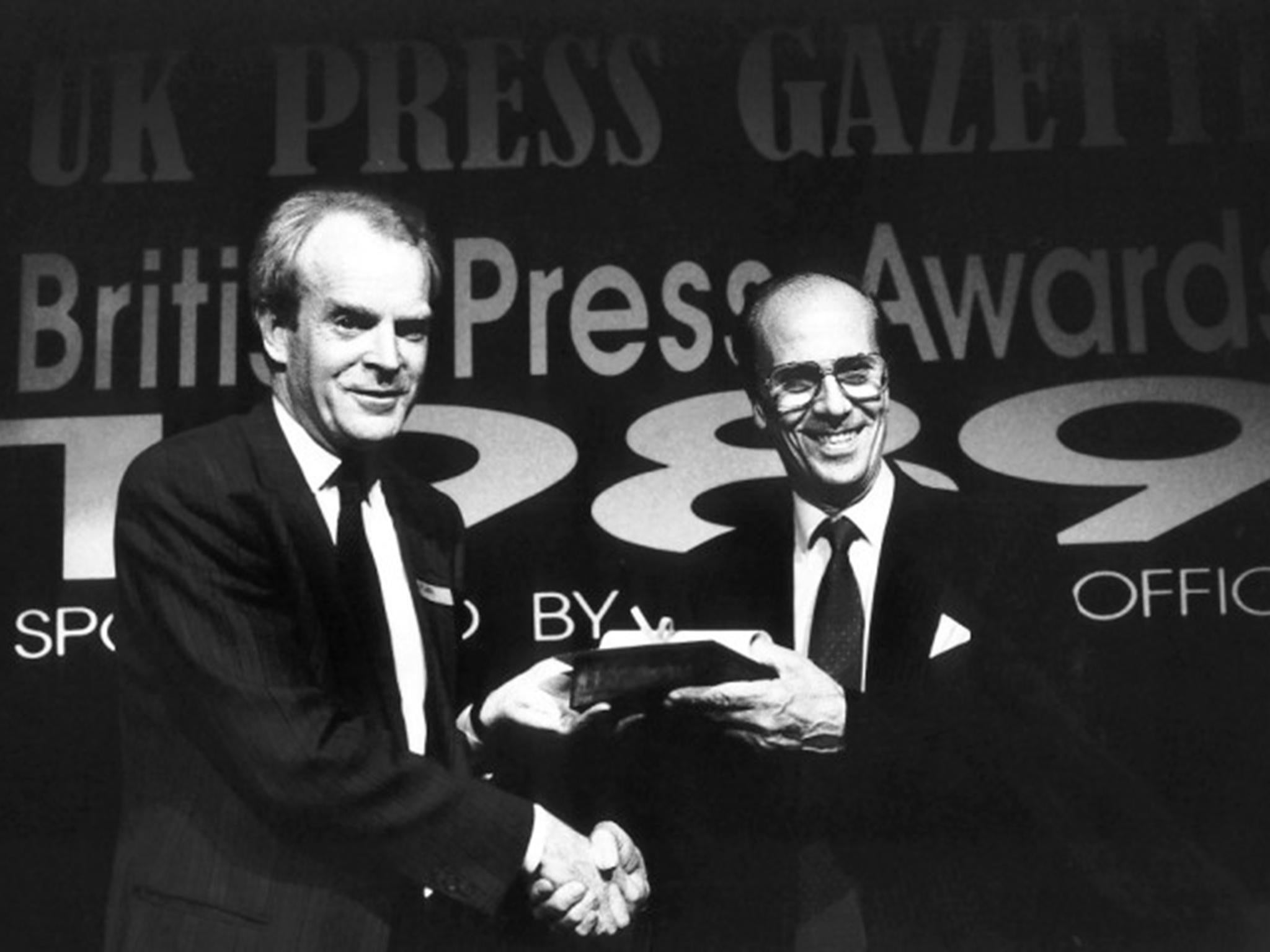

The Independent quickly gained a reputation for the quality of its foreign coverage – and Rupert Cornwell’s magical writing was a key reason for that. He gained a coveted Foreign Correspondent of the Year award when the newspaper was still less than a year old. For anyone who was interested in the Soviet Union, his writing became a must-read – not just the news and opinion pieces, but also his weekly column (‘Out of the USSR’) which always shed interesting light on the ever-changing (or unchanging) Russian and Soviet society.

Sir Andreas Whittam Smith, the paper's original editor, said that as Moscow correspondent, Rupert had been very important to the newspaper's launch and success, reporting on the largest geopolitical story of the post-war era.

“He has died thirty years later still harnessed to The Independent. So to his courage, we can add loyalty. And what a journalist Rupert was,” said Sir Andreas.

I was East Europe Editor of the paper for part of that time and Rupert and I often worked side by side in the cramped Moscow office that adjoined the newspaper's apartment. He liked to say that a foreign correspondent’s best pieces are written when he or she first arrives (seeing things with a fresh eye) or when leaving a country (with a deep understanding of the country).

In truth, there was no point when Rupert’s writing became stale or dull. That was true of his five years’ writing about Russia between 1986 and 1991, and true of his two decades of observations about the United States.

As a tribe, journalists are not always known for being self-effacing. But, from those who worked with Rupert over the years, three words come up again and again: gentle, modest, generous. He was as excited by younger journalists he worked with as by reading a strong piece by a competitor.

None of which means he was necessarily an easy colleague to work with, especially for his editors. His bosses learned that if Rupert had a strong view on the (ir)relevance of a given story, he would not be easy to shift. One colleague remembers attempting to persuade Rupert, then the paper's London-based diplomatic correspondent, to write a piece to mark the 50th anniversary of Indian independence in 1997 – the subject of much pontification at the time. Rupert was having none of it. “India,” he asked the hapless editor, “I mean, what is there to say?”

His first job after studying ancient and modern Greek at Magdalen College, Oxford was in advertising, which he hated. His first newspaper application was to be a sports correspondent (he included a write-up of an Arsenal game as a demonstration of his writer’s skills). Sportswriting remained a love to the end of his life.

In 1968, he joined the Reuters graduate trainee scheme and worked in the news agency’s office in Brussels where he met his first wife, Angela Doria, an Italian interpreter at the European Parliament.

They moved to Paris when he was hired by the Financial Times, and their son Sean was born in 1974. From Paris they moved to Rome, where he wrote a book on the scandal surrounding the collapse of the Vatican bank, God’s Banker: The Life and Death of Roberto Calvi.

From Rome, he was posted to Bonn in 1983. The marriage to Angela ended, though they remained on good terms. It was in Bonn that he met Susan Smith, an American reporter with the Associated Press. They moved together to Moscow, where Susan worked for Reuters news agency, and married in 1988.

From Moscow, they moved in 1991 to Washington DC, and lived there for most of the next quarter of a century. (The family lived in London from 1997 to 2001, when Rupert was diplomatic correspondent). Susan works for Reuters on Capitol Hill; Rupert was The Independent’s Washington bureau chief, and then chief commentator in the United States.

Rupert’s older half-brother David – better known as John le Carré – has written vividly about their father, Ronnie Cornwell, an emotional and financial fraud on a grand scale, as partly described in Le Carré’s semi-autobiographical novel, A Perfect Spy. In Le Carré’s mosaic-memoir The Pigeon Tunnel, published last year (Rupert’s verdict: “terrific”), their father is described as “conman, fantasist, occasional jailbird....Ronnie’s entire life was spent walking on the thinnest, slipperiest layer of ice you can imagine.”

Rupert once recalled to the New York Times how he and his younger sister (the actress Charlotte Cornwell) washed up in an aunt’s house because of his father’s exploits; they had two pounds, twelve shillings and sixpence between them. He remained close to Jean, his mother, throughout her life.

Rupert loved to point out that many of le Carré’s most apparently outrageous stories about the father, “Rick”, in A Perfect Spy were in fact drawn straight from Ronnie-reality. Shaking his head in laughing disbelief, Rupert would say: “You can look it all up in the newspaper archives. Unbelievable!”

The contrast with his own family life was striking. Life with Susan, and with their son Stas (whose wedding Rupert attended last year) were anchors of pleasure and stability, a constant reference point. At a dinner a few months ago in London with colleagues from the early days of The Independent, his eyes lit up as he described the updates from Stas, his older son Sean and his children, and Susan.

The only other thing that mattered almost as much as family was his beloved baseball. (And, even from afar, the fortunes of Arsenal.) One email, sent during his treatment for cancer, ended with news of his young grandchildren and the fact that the Washington Nationals, where he and Susan had season tickets, were in the playoffs. His conclusion: “Life’s not without its compensations.”

Rupert Howard Cornwell, born 22 February 1946. Married Angela Doria, 1972 (dissolved); Sean, born 1974. Married Susan Smith, 1988; Stas, born 1989. Died, Washington DC, 31 March 2017

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments