Faith schools and grammars the most ethnically and socially segregated in UK, warns charity report

Charity calls for social segregation to be addressed as over half of England's primary schools found to becoming increasingly divided

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Thousands of England's schools are segregated by ethnic or social status, new research has revealed, with faith schools and grammars found to be the most divided of all.

A report published by social integration charity The Challenge reveals that in 2016, more than a quarter of primary schools (26 per cent) and around two fifths (40.6 per cent) of secondaries were ethnically segregated.

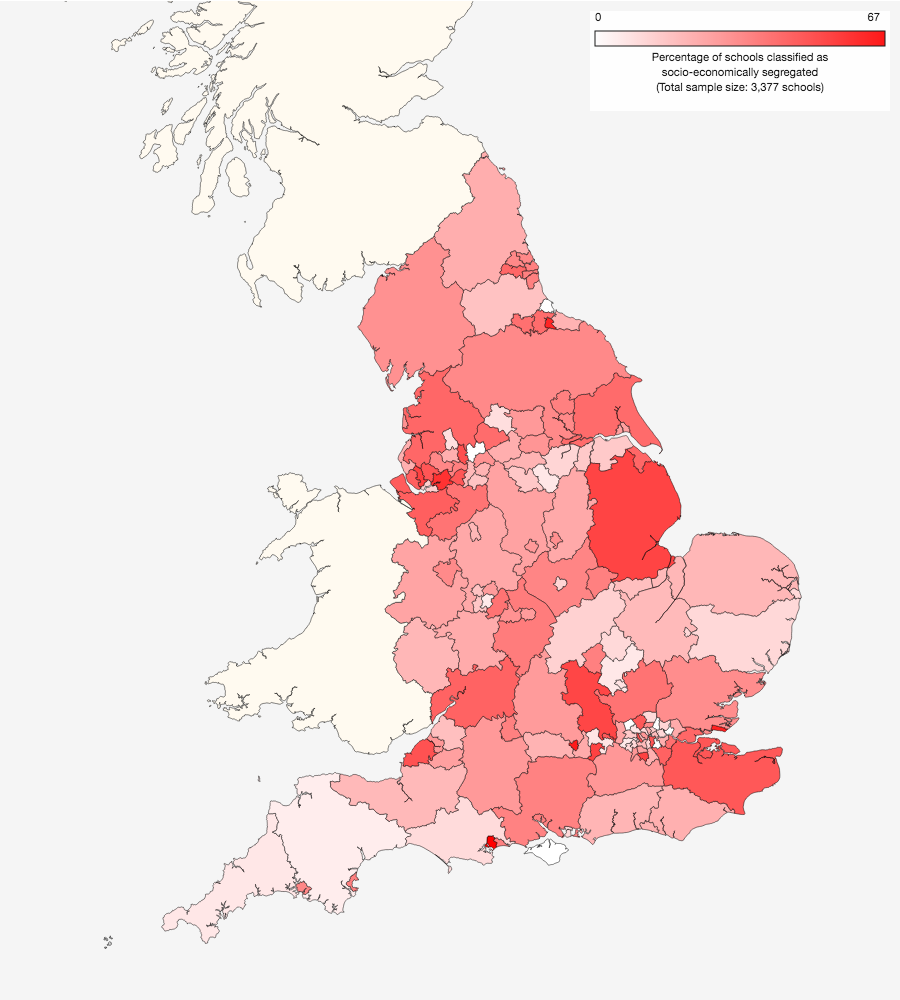

Further to this, nearly three in 10 primary schools (29.6 per cent) and over a quarter of secondary schools (27.6 per cent) are said to be split by social background.

This means that many schools across the country have pupil populations made up overwhelmingly of either white British or ethnic minority children, or have large numbers of pupils from either rich or poor homes.

The charity has called for more to be done to diversify schools and make intakes more representative of their local communities.

Researchers from the charity, working with the iCoCo Foundation and data crunching group SchoolDash, examined how segregated a school was by comparing the numbers of white British children and populations of those with free school meals (FSM) eligibility against those of the 10 schools closest to them.

Using official data for the years 2011 to 2016, researchers’ analysed the make-up of more than 20,000 state schools.

A school was considered “segregated” if the proportion of ethnic minority pupils or pupils on free school meals was very different to the proportions at the 10 closest schools.

The study found that secondary schools are more likely to be segregated by ethnicity while primaries are more likely to be divided along socio-economic lines.

Some of the areas with the highest levels of ethnic segregation include Blackburn with Darwen, Lancashire, where over 71 per cent of primaries and 83 per cent of secondaries are schools with high or low white British school populations in relation to the overall local population.

Kirklees, West Yorkshire, Tower Hamlets borough in London, and Rochdale, Lancashire, were found to have some of the most ethnically divided school communities.

Faith schools are more ethnically segregated than those of no faith (28.8 per cent against 24.5 per cent) when compared with neighbouring schools, the study found.

Religious primary schools overall were more likely to have a wealthier student population, with over one in four (27 per cent) having significantly fewer disadvantaged pupils than other nearby schools, compared with 17 per cent of non-faith primaries.

The difference was especially pronounced in Roman Catholic schools.

‘The collective impact of faith schools, particularly the predominant Catholic and Church of England schools which are by far the most numerous, needs to be examined,” the report’s authors said.

As an example, the charity highlighted how in one London Borough, the 17 faith primary schools that have somewhat diverse intakes take between one and five times the proportion of White British pupils compared to the area, which in turn “substantially reduces the potential for other schools to become more mixed”.

Reacting to the findings, British Humanist Association (BHA) Education Campaigner Jay Harman said: “Once again, the evidence is unequivocal. ‘Faith’ schools are not a positive feature of a diverse and integrated society, as is so often claimed.

"Rather, they are a barrier to integration and a barrier to the promotion of mutual understanding and respect between people from different religious, ethnic, and socio-economic backgrounds".

The Catholic Education Service insists their schools are "the most ethnically diverse in the country," however, educating significantly more pupils from minority backgrounds than the national average.

"Catholic schools also take in more pupils from the poorest backgrounds than other schools, a spokesperson from the organisation said.

“What’s more, comparing Catholic schools to their neighbouring schools is a fruitless task as the catchment area for Catholic schools is, on average, ten times the size of other schools.

“It is precisely because they draw in a variety of pupils from a much wider area, they are more ethnically mixed than their surrounding schools.”

At secondary level, schools rated as “inadequate” tended to be more ethnically segregated, while those judged “outstanding” by inspectors were more likely to have a representative mix of pupils, compared with neighbouring schools.

And grammars schools - which have been the subject of much protest following the Government's announced plans for expansion - were severely segregated by social background.

Some 98 per cent of these selective schools had low numbers of poorer pupils, compared with their local schools, and none had pupil populations with high numbers of free school meal students.

The study also suggests that in some areas the situation is worsening - with primaries becoming more ethnically segregated in the last five years in over half of the 150 areas analysed.

Jon Yates, director of The Challenge, said: “This study shows far more needs to be done to make sure school intakes are representative of local communities.

”As the Government's Casey Review pointed out, segregation is at a 'worrying level' in parts of the country.“

Local and national government need to commit to doing more to reduce school segregation, he said.

”We know that when communities live separately, anxiety and prejudice flourish, whereas when people from different backgrounds mix, it leads to more trusting and cohesive communities and opens up opportunities for social mobility.

“We urge local authorities, faith schools and academy chains to consider the impact admissions policies have upon neighbouring schools and put policies in place that encourage better school and community integration.”

A Department for Education spokesperson said: “We expect all schools to promote social integration and the fundamental British values of democracy, the rule of law, individual liberty, and mutual respect for different faiths and beliefs.

“Our free schools programme already encourages applications for free schools which aim to bring together pupils from different ethnic or faith groups, and our consultation, Schools That Work For Everyone, includes faith schools setting up twinning arrangements with others not of their religion so that pupils mix with children from different communities and backgrounds.

“But we know there is more to do. The Casey Review highlighted a number of issues around levels of ethnic segregation in school intakes in some areas of the country. The Government is considering the review and its recommendations and will respond in due course.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments