The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

‘Sometimes you’re not making a good choice’: Unpacking our cultural obsession with baby names

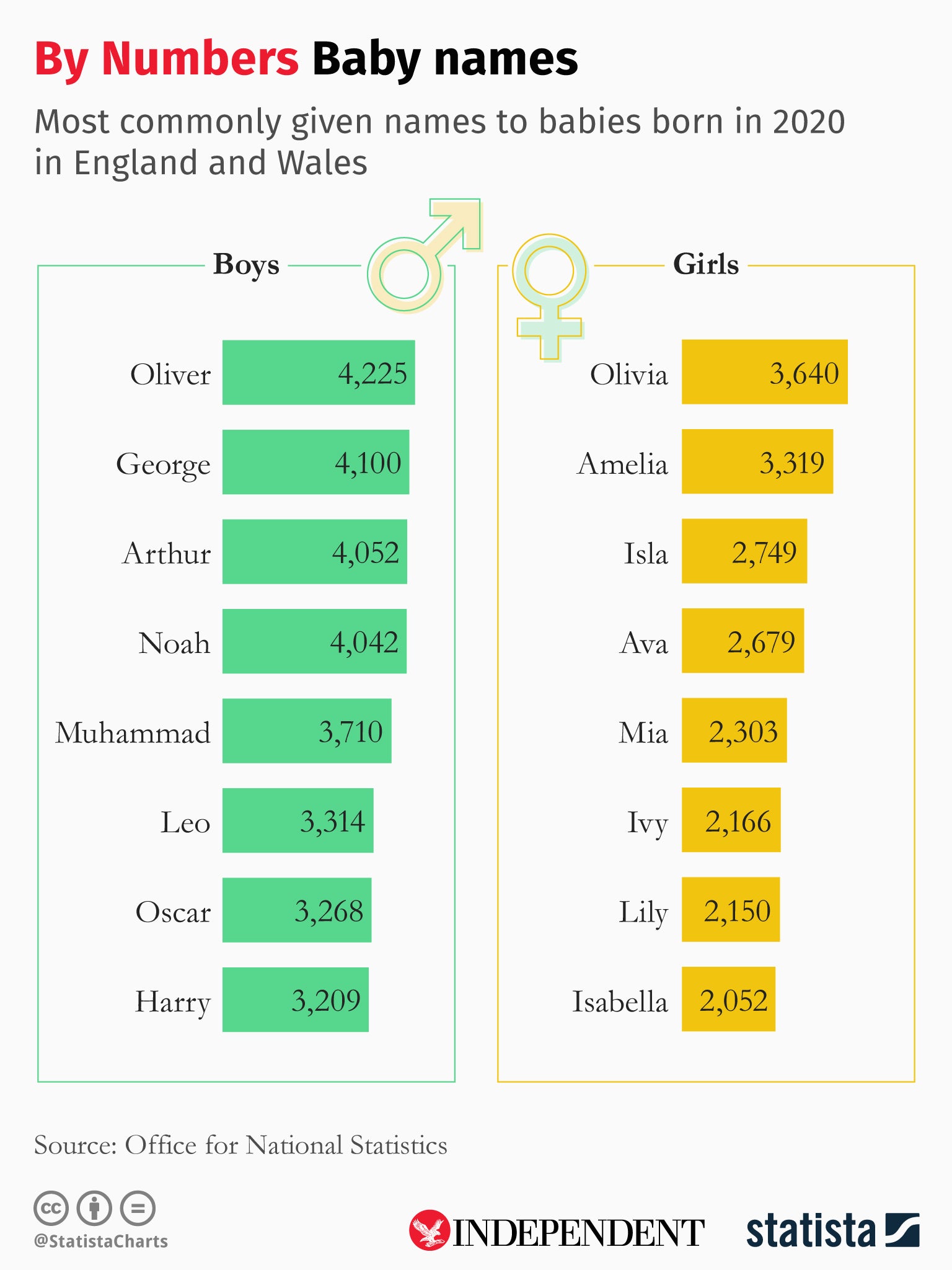

As the ONS’s annual statistics on the most popular baby names in England and Wales are released, Moya Crockett asks why we are so fascinated by what other people choose to call their children

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Last Monday, as she does every Monday, SJ Strum sat down in her living room in Surrey and recorded a YouTube video about baby names. “Today is a rapid-fire name list, and a reveal of the UK’s number one guilty pleasure baby name – which is a name everyone loves, but not everyone is brave enough to use,” she says, before rattling through more than 350 names in under 12 minutes. These names, which Strum had crowdsourced via her 17,700 Instagram followers, included Goldie (“vintage vibes”), Tarquin (“quite upper-class”), and Tallulah (“sounds great in theory, but when you’re actually saying it in the playground, you feel maybe it’s too much”). The most popular “guilty pleasure name”, Strum announced, was Tigerlily.

Strum is a motherhood blogger and baby name consultant in her late thirties. When she first launched her YouTube channel almost six years ago, she covered a scattergun range of topics – from the myth of “having it all” to the sadness she felt after stopping breastfeeding. But when she made a video titled “Unique and Unusual Nature Inspired Baby Names” in September 2016, she realised she’d hit on a subject that resonated.

“People were like, ‘I loved that list – do another one!’” she says. She followed up with videos on the “hottest baby name trends”, “hipster baby names” and “baby names I love… but won’t be using”. The views ratcheted up, and before long, Strum was receiving messages from strangers who wanted help naming their unborn children. “People would contact me saying things like, ‘I’m having my first daughter and I like the names Juniper and Lola – what should I call her?’ I realised how much appetite there was for these conversations.”

Today, Strum has around 115,000 subscribers on YouTube, where the majority of her videos are baby name focused. She also hosts a podcast, Baby Name Envy, where she suggests names for listeners who can’t decide what to call their child, and runs a popular Instagram page with the same title. She says she spends around 45 minutes to an hour researching name suggestions for each prospective parent featured on the podcast, a service she provides for free. “I make my money through brand sponsorships,” she says. “I probably earn the same as I did when working in advertising in London full-time.”

Strum is something of a UK celebrity on the baby name internet. But if you share her fascination with given names, her feeds aren’t the only place to spend time. As well as the big-hitting websites such as Nameberry, BehindTheName and BabyNameWizard, there are dozens of English-language Facebook groups and Reddit forums, with well over 500,000 members collectively. In this corner of the web, the Office for National Statistics’ annual chart of the most popular names in England and Wales is awaited with bated breath. Several recent threads on Mumsnet’s Baby Names Forum were given over to detailed predictions of which names would rise and fall, much like cricket fans might debate the outcome of the Men’s T20 World Cup.

“Bobby [will] rise from 68th [place] and Robert from 115th,” predicted one Mumsnet user. “Oakley to fall out of top 100 (at 98th in 2019 data)… Harper to fall from 29th [and] Willow to rise slightly from 19th.”

Perhaps predictably, the majority of Strum’s audience are women in their twenties and thirties, who one assumes are either pregnant or planning on having a child relatively soon. But it’s not the case that only people awaiting the arrival of a new baby are interested in name trends. “Given names can be a source of fascination even if you aren’t planning on having children, because they’re so rich and deep in terms of identity issues,” says Dr Jane Pilcher, associate professor of sociology at the Nottingham Trent University, who happily describes herself as a “name nerd”.

“I totally understand why people get excited when new name data comes out – I do, too,” says Pilcher. "We’ve all got a name – it was fixed to us before we were even conscious beings. Then layer on all the other ways our given name identifies us: it might just not indicate our gender, but potentially our age, social class and ethnicity too. There’s a lot to think about.”

Given names can be a source of fascination even if you aren’t planning on having children, because they’re so rich and deep in terms of identity issues

It’s true that name trends have always revealed a lot about the societies in which those names are bestowed, which helps explain why we had to endure several dog-whistling newspaper articles in the 2010s about whether Muhammed really was the most common boys’ name in England and Wales (it wasn’t). English Puritans in the 16th and 17th centuries often favoured dour names that referenced moral virtues, sin and suffering (think Abstinence, Humiliation and Kill-sin). In traditional Igbo culture, given names are weighted with literal and symbolic meaning – but according to one 2018 study, recent decades have seen a shift towards Igbo parents in Nigeria giving their children shorter, more westernised names. Common names have become progressively less popular in the US since the 1950s, something researchers attribute to an increasingly individualistic society. It seems likely that public interest in names has risen as the range of names being given to children has expanded.

“Over the 20th century we started seeing a tremendous amount of creativity in the names that were given in the US and UK, and popular names turning over much more quickly,” says Dr Laurel MacKenzie, assistant professor of linguistics at New York University. “People aren’t choosing the same names over and over anymore, which keeps things interesting.”

Celebrities clearly inspire parents to be more creative in naming their children: Luna soared into the top 100 girls’ names in England and Wales after Chrissy Teigen and John Legend chose the name for their daughter in 2016 (in the 2020 rankings, it jumped up again, to become the 36th most popular girls’ name), while there was a 367 per cent rise in baby boys called Bodhi in the three years after Megan Fox gave the name to her second son. But seriously out-there celebrity baby names (think Chicago, Apple and Atom) have yet to be adopted by the masses. “Celebrities get away with [giving their children unusual names] because they’re in an elevated position in society,” says Pilcher. “That privilege can protect them, and their children, from the ostracising or judgement that ordinary people might face for their name choices.”

Ah, yes: the J-word. For many people, an interest in baby names is driven – at least slightly, even if they won’t admit it – by the desire to judge other people’s choices. This can manifest in harmful ways: studies show names deemed easier to pronounce are viewed more positively and correlate to higher positions at law firms, while job applicants with stereotypically black or “foreign” names may be vulnerable to discrimination during hiring processes. But there are less pernicious ways to indulge in name judgement, too. Ash Bond, a 24-year-old father-of-one from Rotherham, is the co-moderator of two Facebook groups for “name nerds”, with more than 18,000 members between them.

Names tell us something about the spirit of our times

Members of these groups are welcome to “roast” – ie, cheerfully mock – other people’s favourite names (recent targets of good-natured criticism included Huckson and Parker for boys, and Heavenleigh and Chaisley for girls). Many members of these groups aren’t looking to name their children: some are simply into etymology or deciding what to call a character in The Sims. Bond, who is trans, consulted the groups when selecting his masculine middle name. “Sometimes you’re not making a good choice with a name, and that’s OK,” he says. “We’re there to tell you when you’re making a bad decision and suggest some better alternatives.”

As long as trends keep fluctuating, name nerds will always have something new to talk about. “Names tell us something about the spirit of our times, and different communities have to unconsciously work out their ideas about good naming practises,” says Professor Rajend Mesthrie, a linguist at the University of Cape Town who has studied changes in personal names among Indian South Africans. “There’s a whole lot of humanity hanging behind our choices.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments