US bans imports from China’s Xinjiang to raise stakes in forced labour crackdown

A new law blocking imports tainted by the slave labour of Uyghur Muslims will prove challenging for companies to follow and officials to enforce, writes Kieran Guilbert

The US has passed a law banning all imports from China’s Xinjiang region, signalling its strongest crackdown on slave labour to date and delivering a rebuke to Beijing over its treatment of Uyghur Muslims.

While the US already has legislation blocking the entry of slave-made goods, the newly-passed Uyghur Forced Labour Prevention Act goes further by shifting the burden of proof to importers, and will pose a fresh challenge for companies and customs officials alike.

The act was passed unanimously by the Senate on Thursday and is set to be signed by US president Joe Biden imminently.

The bipartisan legislation essentially deems that all goods from Xinjiang are made with forced labour and cannot be imported into the US unless officials determine with “clear and convincing evidence” that the products are not tainted by modern slavery.

UN experts, rights groups, and researchers estimate more than a million people, mainly Uyghurs and other ethnic minorities, have been detained since 2016 in camps in Xinjiang, where exploitation ranging from torture to forced labour is believed to be systematic.

Companies that source from China – especially goods such as shoes, shirts and solar panels – will need to dig deeper into their supply chains and be more vigilant to demonstrate they are not profiting from the labour of Uyghurs, while US Customs and Border Protection (CBP) must step up its game to enforce the new law, according to analysts and activists.

The law comes at a time when the relationship between the two superpowers has become increasingly strained, over issues ranging from Beijing’s aggression towards self-governed Taiwan to the detention and control of Uyghurs that the US has labelled as genocide.

Frankly, this law needed to happen a long time ago

A fresh war of words broke out last week following Washington’s decision to stage a diplomatic boycott of the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics – citing human rights “atrocities” – and the passing of this law is likely to further inflame tensions.

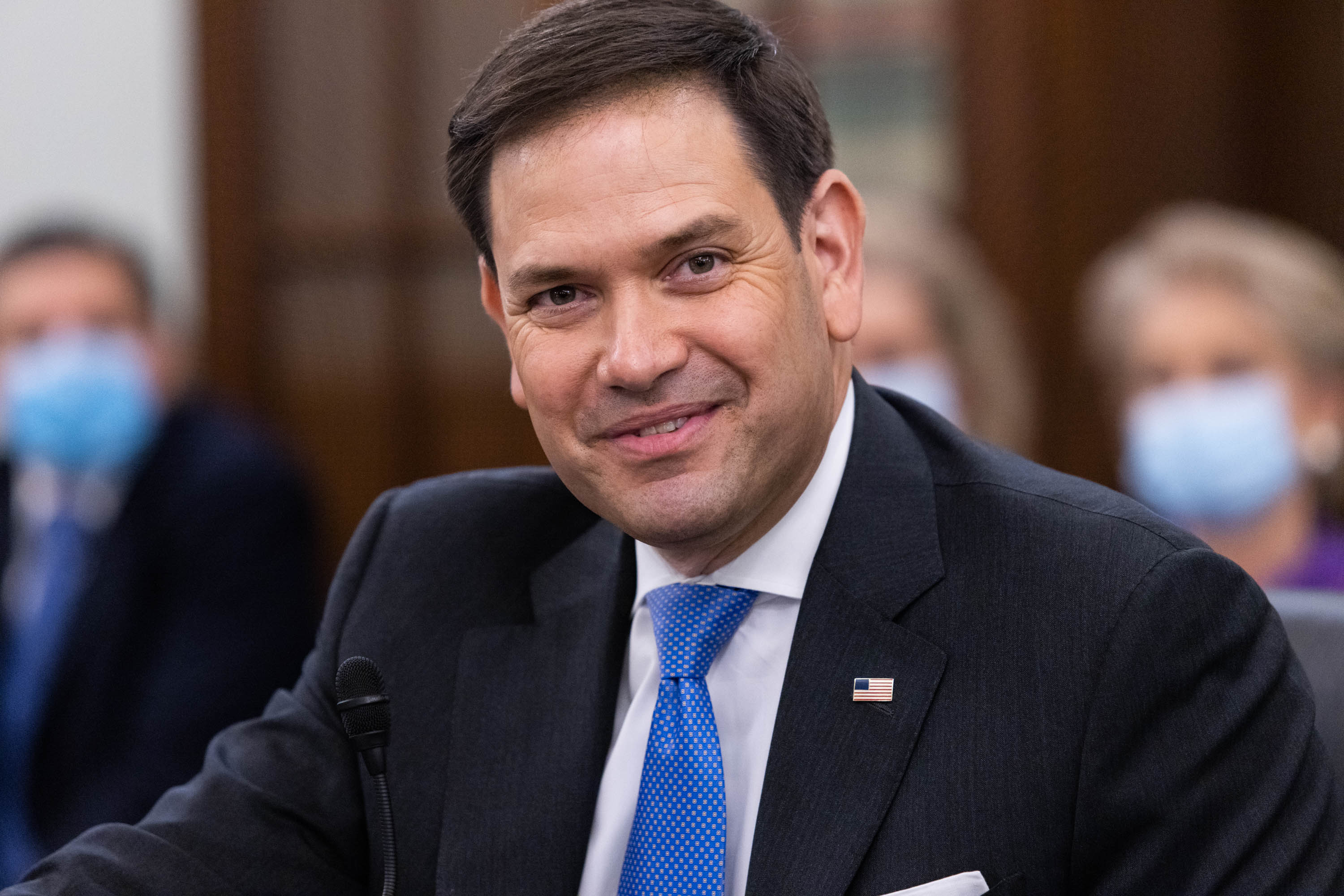

Republican Senator Marco Rubio, who co-sponsored the act, this week said it was “time to end our economic addiction to China” by cracking down on slave labour.

“The US is so reliant on China that we have turned a blind eye to the slave labour that makes our clothes, our solar panels, and much more,” Mr Rubio said in a statement before the law was passed.

Although Xinjiang’s overall exports dropped 12.2 per cent to $15.8bn (£11.9bn) last year, according to customs data, shipments to the US more than doubled to $636m despite the onset of the pandemic and escalating tensions between the two nations.

Beijing has repeatedly denied abuses of Uyghurs and said that all labour in Xinjiang is consensual and contract-based.

The Chinese embassy in Washington said the act was a “vile scheme” and that it opposed the US’s interference in China’s internal affairs “under the pretext of Xinjiang-related issues”.

“China is determined in safeguarding its national development interests. We will make a resolute response if the US insists on advancing the act,” a spokesperson said in a statement emailed to The Independent.

Under the existing Trade Facilitation and Trade Enforcement Act of 2015, CBP officials can stop the entry of goods if there is reasonable evidence of forced labour.

A company issued with a “withhold release order” (WRO) can decide to reroute the shipment and try to sell their products elsewhere, or persuade CBP to change its decision by providing documents to demonstrate due diligence and argue that the goods are slavery-free.

The agency can go further, seizing cargo and pursuing civil penalties against corporations if it has enough evidence to meet the more stringent legal burden of “probable cause”.

Regarding Xinjiang specifically, the US has upped the ante in recent years by issuing a flurry of WROs on goods from the province, while the Trump administration announced an import ban on all cotton and tomato products in January.

Corporations have profited from Uyghur forced labour for years

Campaign groups have long been calling for a region-wide crackdown and welcomed the new law, although there was disappointment over a compromise between the US House and Senate that led to the removal of a requirement for publicly traded companies to report their operations in China.

“Frankly, this [law] needed to happen a long time ago,” said Corban Teague, a senior adviser at the non-profit Humanity United Action.

“We should not let the perfect be the enemy of the very good, and the final product negotiated between the chambers is a strong one,” Mr Teague told The Independent.

The US has long positioned itself as the global leader in efforts to tackle modern slavery – from its annual report ranking nations on their anti-trafficking efforts to a biennial list of goods at risk of being made by forced or child labour – yet the new law is unprecedented in its scope.

The legislation not only covers goods produced in Xinjiang, but also those made by Uyghurs transported to work elsewhere in China under state schemes and products imported from other countries that contain materials tainted by forced labour involving the ethnic minority.

Two such examples would be clothes made in Bangladesh that consist of cotton picked by Uyghurs, or solar panels manufactured in Malaysia that use raw polysilicon materials from Xinjiang. The region accounts for about 20 per cent of global cotton production – and nearly half of the world’s refined polysilicon.

Most businesses lack full visibility of their supply chains, they tend to know their main “Tier 1” suppliers but are not aware of the myriad producers stretching down to the raw materials level, meaning they will have to up their game – and do so quickly – to comply with the law.

Human Rights Watch’s China director, Sophie Richardson, told a Senate hearing on Xinjiang in June that some companies “seem unwilling or unable” to find out precise information about their own operations.

Yet Scott Nova, executive director of the Worker Rights Consortium (WRC), a nonprofit, said corporations had the ability to carry out effective supply chain tracing – if they chose to do so.

“When it suits them, global corporations exercise painstaking control over what happens in their supply chains,” Mr Nova said. “When corporations don’t know where their goods are coming from, it is because that ignorance suits their purposes.”

While it would be impossible for companies to access and inspect factories in Xinjiang due to the government’s tight control, experts said they could invest more in supply chain mapping whether that involves using publicly accessible sources such as shipping and customs data, or new technologies including isotype tracing that shows the origin of the materials in a product.

How multinational corporations will respond to the law remains to be seen.

Some of the world’s biggest brands and several industry groups lobbied to weaken the act last year when it was in bill form, according to a New York Times story from December 2020.

The American Apparel and Footwear Association welcomed the law and said in a statement that it would work with CBP to ensure enforcement of the act was “transparent and evidence-based”. This represented something of a U-turn given that the industry group last year said a Xinjiang region-wide ban would be impossible to enforce and “wreak havoc” on legitimate supply chains.

CBP officials will also have a major task on their hands in trying to deduce if products or their materials originated from Xinjiang or the labour of Uyghurs, several advocates said.

The agency’s forced labour division has historically been understaffed and underfunded, and a report by the US Government Accountability Office in October 2020 found that its ban on slave-made goods was hampered by a lack of skilled employees and reliable data.

In response to a series of questions sent by The Independent, CBP said it “does not comment on proposed legislation before Congress”.

While debate about the feasibility of the law is likely to rumble on, Mr Nova of the WRC was unequivocal on its importance.

“Global corporations have been profiting from Uyghur forced labour, in de facto collaboration with the Chinese government, for years,” he said.

“This legislation will go a long way toward putting an end to their complicity.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments