What the rare meeting between Erdogan and MBZ means for Turkey-UAE relations

Despite their differences, Abu Dhabi and Ankara may have decided that cooperation will prove more effective than conflict, writes Borzou Daragahi

They have been on opposite sides of ferocious hot wars and lobbed media bombs at each other in a years-long cold war.

But Turkey and the United Arab Emirates are putting aside years of hostilities in favour of a tentative rapprochement that includes business and security arrangements that would have been unthinkable even months ago.

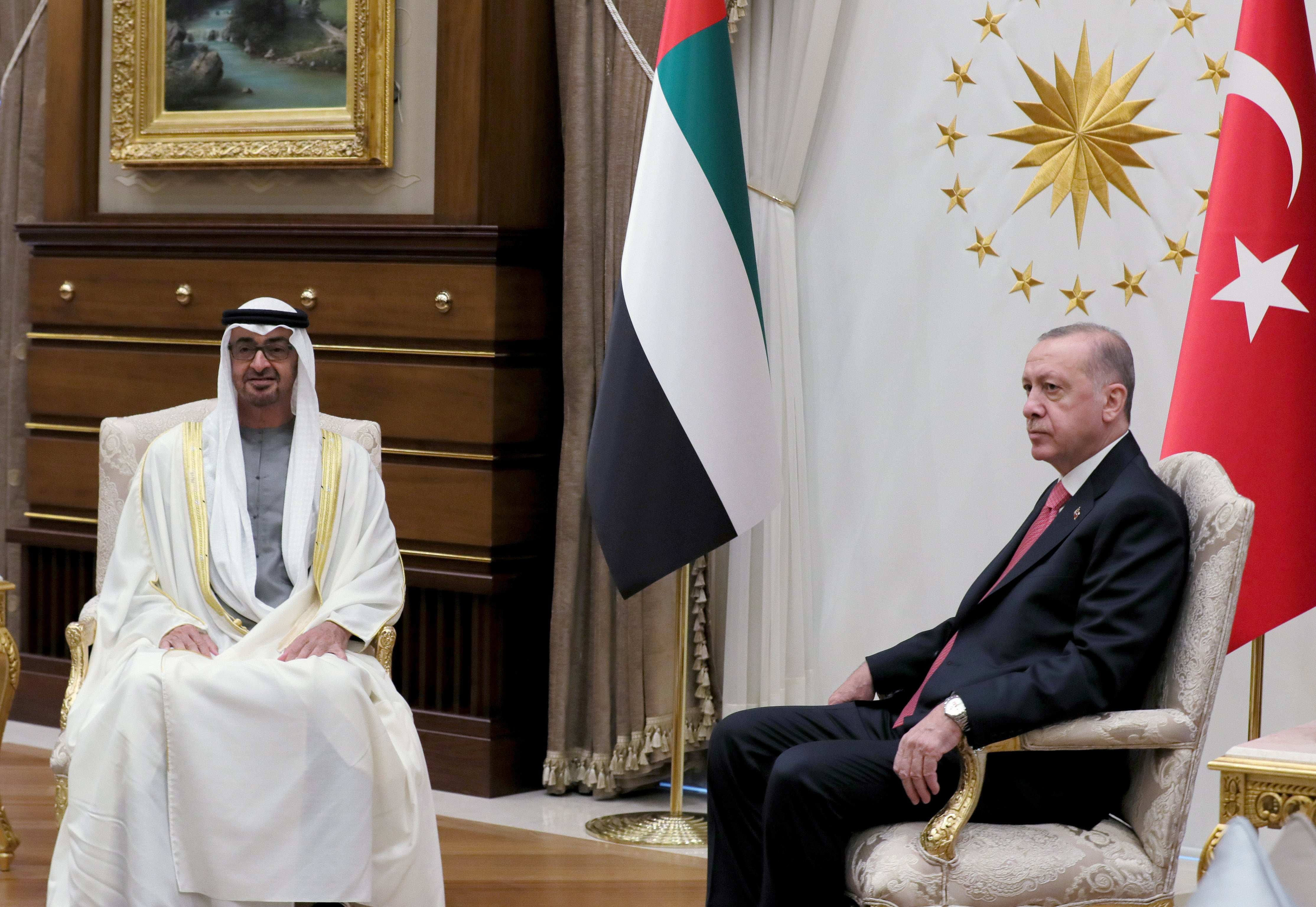

Crown Prince Mohammed bin Zayed, de facto leader of Abu Dhabi and the most powerful figure in the confederation of the seven monarchies that make up the UAE, arrived in Ankara on Wednesday for a momentous meeting with Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan.

Mr Erdogan, greeting the Crown Prince - known as MBZ - in front of the presidential palace in Ankara, afforded him all the pageantry of a full state visit, with national anthems blaring and a 21-gun salute. After closed-door talks, Turkey’s president was to host the Crown Prince for an official dinner in his honour, according to the Anadolu News Agency.

It was the first formal meeting between the two heads of states since nearly a decade ago, when both countries were collaborating in a western-backed effort to bring down the Syrian regime of Bashar al-Assad.

But since then, the two sides have clashed over ideological differences as well as strategic ambitions. Turkey supports the Muslim Brotherhood organisation that the UAE staunchly opposes. The two countries remain embroiled on opposite sides in a vicious proxy war over control of Libya.

Analysts and diplomatic insiders described a number of factors behind the rapprochement. The Libya war has subsided with a tentative victory by Turkey’s allies, and major military setbacks for warlord Khalifa Haftar, who has been heavily backed by the UAE.

It’s about getting the region’s security architecture together

The tumultuous Donald Trump, who allegedly had unsavoury links to Arabian Peninsula autocrats and encouraged the UAE to pursue an adventurous foreign policy, is no longer president of the United States, prompting a normalisation in the region.

“Nature is healing,” joked one senior official.

The UAE may have concluded that it could leverage its economic strength to cajole Turkey on foreign policy issues, perhaps far into the future. Turkey is scheduled to hold crucial presidential elections in 2023, and Mr Erdogan and his Justice and Development Party have been faltering in opinion polls.

“The idea for the UAE is about influence and to be able to influence outcomes,” said Theodore Karasik, a Middle East specialist at Gulf State Analytics, a Washington consultancy. “They’re thinking way beyond 2023 in their calculations when it comes to Turkey.”

In recent weeks, the UAE has sought to mend relations with Syria, Qatar, and Iran, and may have also decided the rivalry with Turkey was delivering few benefits.

“I call it competition fatigue,” said Yusuf Erim, a political analyst at Turkey’s TRT World television network. “The geopolitical return on the UAE investments have been diminishing especially in arenas where Turkey is the rival. It comes to a point where removing Turkey from the list of countries that it views as hostile is a geopolitical bonus.”

Security and spy chiefs from the two nations already met in the run-up to the meeting between Mr Erdogan and Prince Mohammed, suggesting an emphasis on hammering out strategic understandings.

Turkey and the UAE share interests in containing Iran’s ambitions and preventing more fallout from the conflict in Syria.

Although they differ sometimes drastically on political visions for the region, they may have concluded that cooperation rather than conflict will prove more effective, especially as the US strives to pivot away from the Middle East and North Africa and toward Asia.

Both countries’ official and unofficial media outlets have been targeting each other with vehement propaganda, and analysts speculated that a toning down of accusations and language could be in the works.

“It’s about getting the region’s security architecture together,” said Mr Karasik. “It is meant to deconflict some of the more contentious issues. They’re looking for breathing space in the region. To get that you have to calm down some of the issues.”

The UAE might also be considering taking advantage of Turkey’s weakened economy to buy pieces of profitable businesses on the cheap. Insiders say that the UAE was considering investments of up to $15 billion in dozens of Turkish firms, especially in the defence and aerospace sectors.

Despite years of tensions, the UAE has long controlled one of Turkey’s most important sea gateways, the Yarimca Port, in the city of Kocaeli just outside Istanbul, and trade between the two countries jumped 21 per cent last year compared to 2019.

The oil-rich UAE is emerging from the Covid-19 pandemic with cash in hand, and Turkey, whose currency has suffered a record meltdown in recent days and has declined in value more than 60 per cent this year, is eager to court foreign investment.

A commentary on Haberturk, a pro-government news outlet, described “intense traffic” between the intelligence and diplomatic services of countries in an effort to improve ties.

“[Diplomats] deem that no party has been victorious in the Cold War that has continued for a decade,” the piece read.

“They say the UAE has paid high prices in the field and in the information war. They also underline the serious political energy Turkey has also wasted in the field and emphasise that both sides should normalise relations without wasting any more energy.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments