‘I lost a lot’: Former political prisoner Kylie Moore-Gilbert reveals toll of 804 days behind bars in Iran

The British-Australian academic speaks to Rory Sullivan about her ordeal in Tehran’s Evin prison, the case of Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe, and the plight of other prisoners who are still detained in Iran

Almost a year and a half after leaving Iranian prison, the British-Australian academic Kylie Moore-Gilbert is still coming to terms with the 804 days she spent behind bars on unsubstantiated espionage charges.

Speaking from her home in Australia, the university lecturer reflected on the horror of being taken as a political hostage by the powerful Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC), who, without any evidence to back up their claims, said she was working for foreign governments.

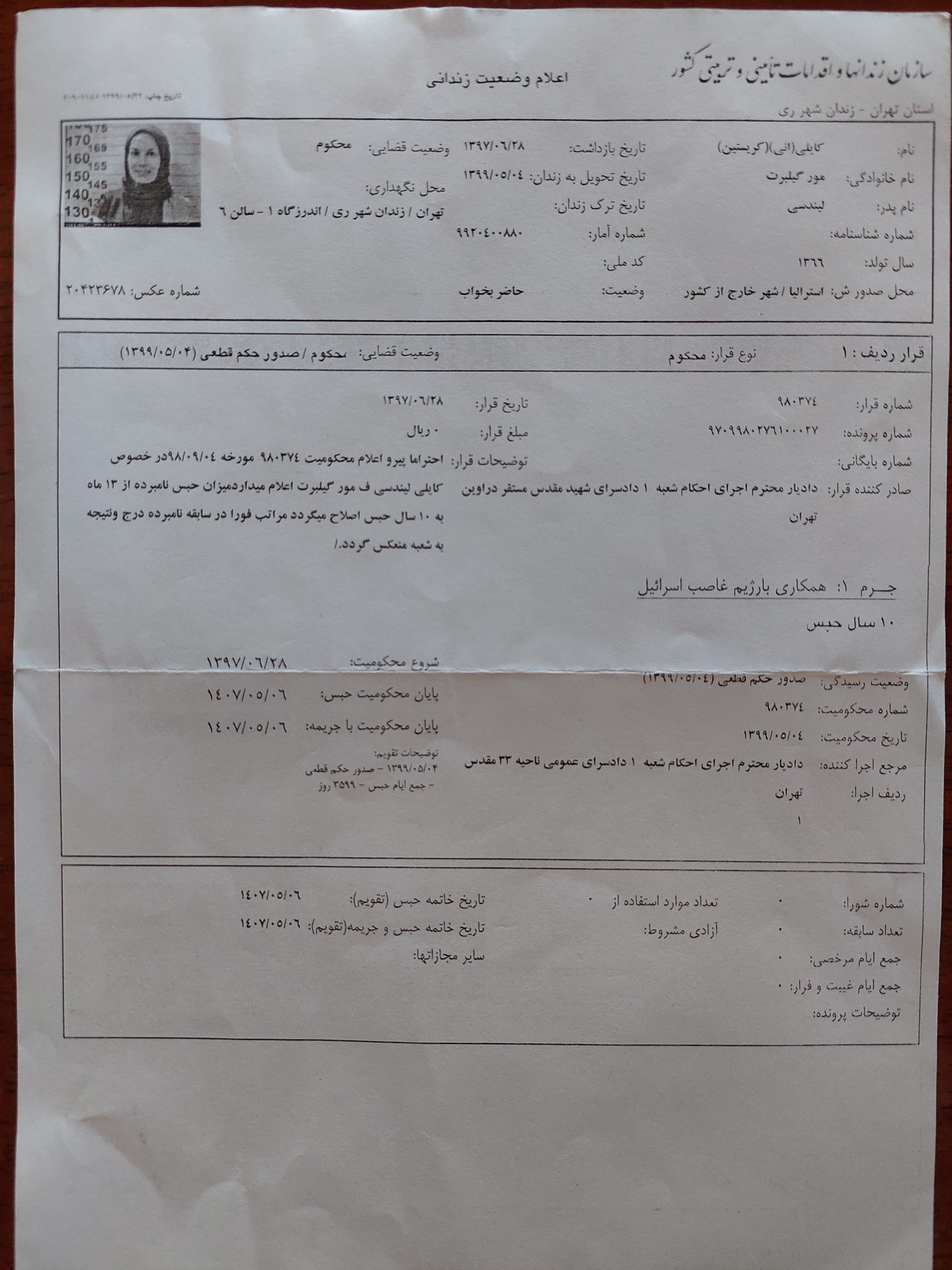

Ms Moore-Gilbert was detained in Iran in September 2018 and handed a 10-year sentence before being released in November 2020 in exchange for three Iranians who had been held abroad.

“Back at home in a familiar environment, I sometimes feel like I had a very vivid, lengthy nightmare one night. And that maybe it wasn’t real and never happened,” she told The Independent, shortly after Iran released her fellow British detainees, the charity worker Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe and the businessman Anoosheh Ashoori.

Ms Zaghari-Ratcliffe and Mr Ashoori landed back in England on 17 March, following the UK’s decision to repay a £400m debt owed to Iran since the days of the Shah. Although Boris Johnson’s government styled their return as a diplomatic coup, ministers have been criticised for not acting sooner – and for not securing the freedom of other innocent British citizens languishing in prison in Iran.

Ms Moore-Gilbert’s own nightmare ended on 26 November 2020. But any sense of elation had to wait, as she knew from experience not to get her hopes up.

Over lunch in the Australian ambassador’s residence in Tehran, Ms Moore-Gilbert understood she was among friends. However, the dual national feared she was vulnerable outside this diplomatic bubble, just as she had been at the time of her unexpected detention in the capital’s airport several years earlier. “I thought, ‘As soon as I leave this building, they can snatch me off the street again. All of this could be a ploy, all of this could be a game’.”

“I didn’t allow myself to think I was free until I’d actually left Iranian airspace. They’d tricked me so many times, there’d been so many diplomatic deals that were cancelled at the last minute,” she said.

Relief finally sank in as her plane neared Qatar, beyond the grasp of the IRGC, her former captors. “I looked out the window at this beautiful sky of stars. Those stars for me represented freedom.”

This motif features prominently in her newly published book about her ordeal, The Uncaged Sky, which contains a passage about the brief respite she achieved by escaping onto the roof of Evin prison, where she spent the majority of her incarceration. She says was later moved to Qarchak jail for spurning the romantic advances of one of her interrogators.

“For the first time I was outside, the breeze in my hair, the sun on my face, without cameras, without guards. Above me was nothing but the uncaged sky, and before me Tehran sprawled as far as the eye could see,” she writes of her moments on the roof.

The sky was especially important for Ms Moore-Gilbert because of all the time she had spent without it. After being interrogated for a week in the ironically named Ideal Hotel, she said she was blindfolded and driven to the women’s ward at Evin prison. There she was dumped into a tiny, windowless cell.

“I thought the solitary confinement cell was so small it was a cubicle for changing into the prison uniform. And then I’d be taken to where I was supposed to be sleeping,” she said.

“I couldn’t comprehend that it would be in that box that I would have to remain for a month. It really was just horrendous.”

Ms Moore-Gilbert’s first few weeks at Evin were the toughest. She said she did not know where she was or who had arrested her, and suffered from sensory deprivation because of the bare room and the glare of a light that was never turned off. Things were all the more difficult because she had not taught herself Farsi at this stage, so she was unable to communicate her basic needs to the guards.

“You’re just left alone inside your own head. And you become your own torturer. Because you have literally nothing to do except ruminate and regret and fall into despair. Sometimes I would just be howling in psychological pain at being there,” the 34-year-old said.

Despite this psychological torture, Ms Moore-Gilbert said she managed not to give in to her interrogators’ demand for a confession of imaginary guilt. In the same way, she said she later repulsed the IRGC’s attempts to turn her into an Iranian double agent.

Left alone with just her thoughts for company, she fell back on memories of her early childhood in Australia, casting her mind back to the games she played with her sister among their garden’s eucalyptus trees, to the fishing trips she went on with her father and to her days at primary school.

“When I was there in that cell, I was amazed that my brain had just evoked those long-buried past recollections,” she recalled.

“They weren’t necessarily happy memories. I numbed my emotion down and tried to not feel anything, including the good feelings. It was more glimpses or snapshots of my past life without any emotionality attached, almost as if I was watching a reel of footage from someone’s camera. I felt detached from it, as in a dream.”

Ms Moore-Gilbert was jolted back to the present by the hostility of her interrogators and by the brutality of some of the guards. As a means of confronting these injustices, she decided to assert her agency whenever she could.

As well as clambering up onto the prison roof, she said she went on repeated hunger strikes, once to remove her roommate, a woman she believed to be an informant.

Another act of defiance she recalled was screaming obscenities at her captors and clinging onto the Australian ambassador’s legs, after a member of the IRGC cut their meeting short. For this, she was given a months-long ban on consular visits and family phone calls.

“I definitely tried my hardest to exert my agency in some way. And I feel like I did manage to influence my fate through my many acts of resistance. Sometimes for worse not for better, but often I did win myself concessions as well,” she said.

Communicating with other detainees was another way to keep herself sane. By whispering through air vents and by stashing messages in secret hiding places, she got to know fellow detainees Niloufah Bayani and Sepideh Kashani, both of whom were environmentalists from the Persian Wildlife Heritage Foundation.

“They educated me during the interrogations, when it was crucial for me to know who had captured me and what they wanted and how things might progress. I don’t know what I would have done if I didn’t have that support. I don’t know how I would have survived.”

The pair later became her cellmates. In spite of their circumstances, there were moments of happiness, as they sang, danced, fashioned their prison uniforms into different outfits and swapped stories about their lives.

Ms Bayani and Ms Kashani, to whom the book is dedicated, were a great comfort for Ms Moore-Gilbert when she was sentenced to 10 years in prison by Abolghasem Salavati, a notoriously hardline judge.

Her friends remain in prison, where they have been for more than four years. “As innocent people, it just breaks my heart,” Ms Moore-Gilbert said.

The conversation turns to the subject of her own release. For the first year of her incarceration, the Australian government kept her detention out of the spotlight. But when her ordeal became public knowledge, it forced politicians to come up with solutions. “Certainly in my case, I don’t think the quiet diplomacy was effective,” she said.

For her, governments should tailor their approach to arbitrarily detained individuals rather than opting for quiet diplomacy as the default option. “There are many cases where the media and public attention can help ensure a person is released. And ensure they’re not brutalised while in custody.”

As an example, she cited the cases of Ms Zaghari-Ratcliffe and Mr Ashoori, who spent six and five years respectively in Iranian jail before they were freed last month. While she is “overjoyed” at their release, she called it a “travesty” that the UK did not ensure that all its citizens returned home.

“I think the British government has played a relatively strong hand very weakly against Iran,” Ms Moore-Gilbert said, suggesting it should have leveraged more concessions from its debt payment.

“It’s a travesty that they left British nationals behind. I don’t think it’s a coincidence they left behind those without public campaigns calling for their release and didn’t have a public profile,” she added.

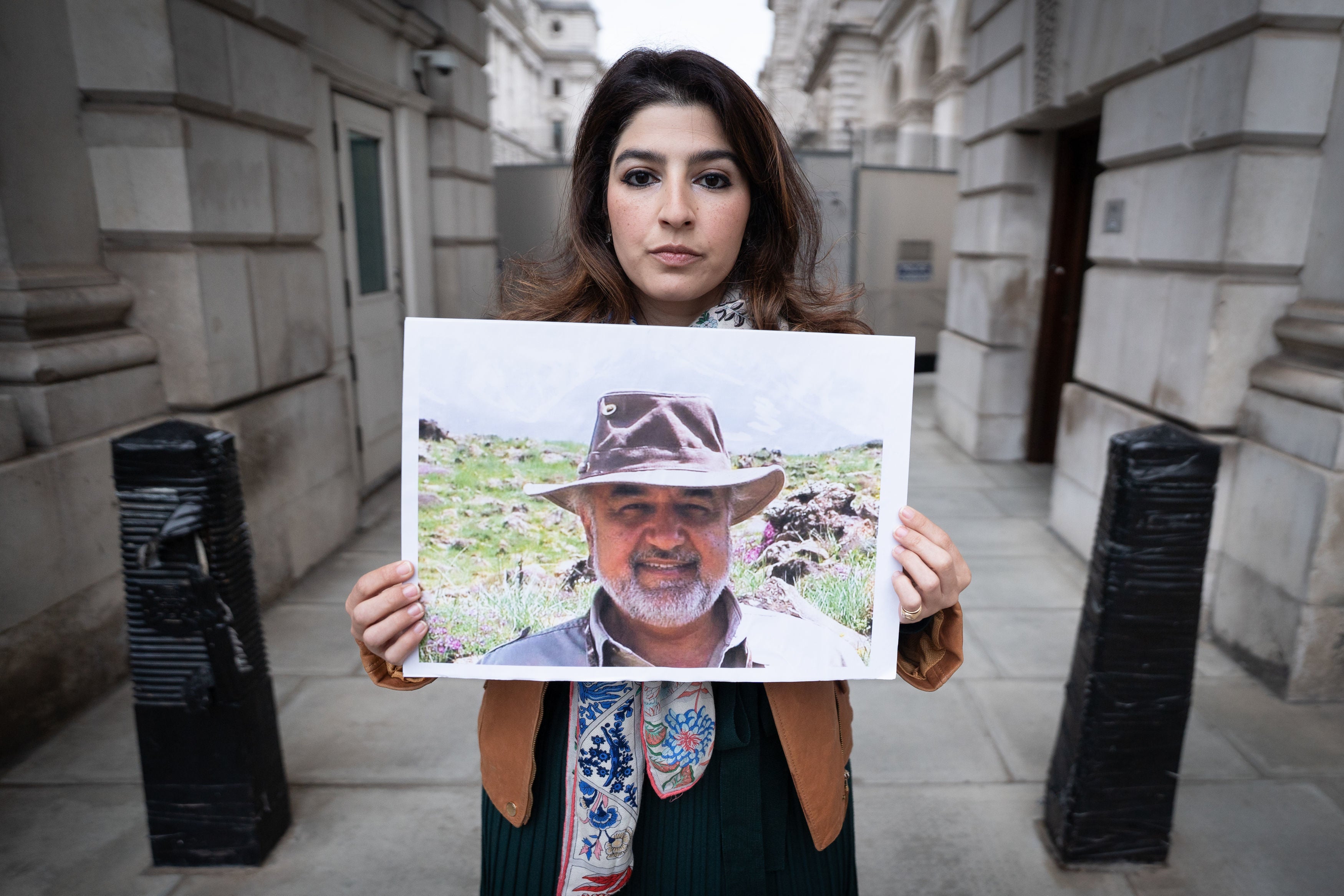

Morad Tahbaz, a wildlife conservationist who holds British and American citizenship, is one of the unlucky ones who remains in Iran. The cancer-sufferer recently started a hunger strike to protest against his treatment.

Ms Moore-Gilbert, who has spoken to his family, said the British government promised he would fly home with the others if a deal with Tehran was reached. “But instead they abandoned him and couldn’t even get the Iranians to stand by their guarantee that he would remain outside prison under house arrest. It’s just shocking,” she said.

On Wednesday, his daughter Roxanne Tahbaz demonstrated outside the Foreign Office in London, saying it was “devastating” for her family to have their hopes dashed.

The Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) has said it is working with the US, where Mr Tahbaz is also a citizen, to secure his permanent release, as well as pushing for the freedom of another detained UK national Mehran Raoof.

Ms Moore-Gilbert would like to see Mr Tahbaz and others gain their freedom soon. But by her own admission, this will only be the start of their roads to recovery, as she learnt upon her return to Australia.

“It’s been a difficult adjustment in some ways. I’ve learnt a lot about myself and about other people as well. And about who has my back and who doesn’t, who was there for me and who disappeared during my incarceration.”

“I lost a lot: I lost my career, I lost my marriage. There’s been a lot to grapple with,” she said. Despite all she has been through, the lecturer, who has now quit academia, remains positive. “Although I’m still recovering, I’m feeling optimistic.”

‘The Uncaged Sky’ by Kylie Moore-Gilbert is published in hardback by Ultimo Press and costs £18.99

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments